The sense of smell in humans: characteristics and functioning

The human sense of smell can be truly amazing, despite the fact that the idea that it is a not very useful, vestigial sense, is still very widespread and ingrained. stunted and more typical of animals than Homo sapiens, a species too rational to be guided for him.

Since ancient times, and especially since the 19th century, smell has been seen as a sense that gives us little information, but thanks to the most recent research in cognitive science we know that this is not So. In addition, cross-cultural studies have shown that there are many languages in which smell is highly relevant.

Next we will talk about the sense of smell, the anatomical structures that make it possible, why it is ingrained the belief that it is underdeveloped in humans and we will also see cases of cultures where it does acquire great importance.

- Related article: "Olfactory bulb: definition, parts and functions"

How is the sense of smell in humans?

Many people still believe that humans have an underdeveloped sense of smell

and that in no way can we compete against other animals, such as dogs or mice, when it comes to identifying odors. For a long time it has been thought that this sense was vestigial in our species and that throughout evolution it has ended up being relegated mainly due to the improvement of our sight and hearing.This has been a very common belief but, thanks to cognitive science and having taken a cross-cultural perspective, it has been shown to be false. The (Western, by the way) idea that humans can't smell very well is an old myth, whose origins date back to the nineteenth century and it has greatly influenced both science and culture popular.

Although it is true that there are many species that are better than us at identifying smells, our sense of smell is as good as that of many other mammals. Humans we can discriminate around a trillion different smells (previously believed to be only 10,000) and despite having a relatively small olfactory bulb, our abilities to recognize odors are better than the scientific community thought in a beginning.

How does it work?

Before we talk further about how the sense of smell has been discredited, let's talk about how it works in humans. Basically this sense It is used to identify chemicals that swarm through the air and that, when making contact with the chemoreceptors found in the nose, a nerve signal is sent to the brain where they are identified as smells.

Inside the human nose you can find three nasal turbinates, one for each of the three nostrils. These turbinates are surrounded by the pituitary, a mucous structure that is responsible for heating the air before it reaches the lungs. The pituitary secretes mucus, the pituita, which moistens and protects the nasal walls. In the pituitary are the cilia which contain thousands of olfactory receptors, some cells that are responsible for capturing the chemicals that enter the nose.

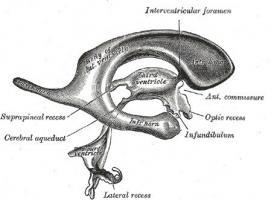

When the chemical substances come into contact with the cilia, a nerve signal is produced by the receptors that are found in them. This signal will be sent through nerve fibers to the olfactory bulb from which the information will go to different regions of the brain where these stimuli will be interpreted and recognized as odors.

Smell and taste are closely related, for this reason when we suffer from a disease in which the nose is affected, it also affects the way we taste food. This is clear when we have colds and we produce a lot of mucus, fluid that clogs our olfactory receptors that prevent us from detecting smells and tastes, which are chemically the same.

- You may be interested in: "The relationship between taste and smell in the human body"

When did this sense begin to be underestimated?

According to John McGrann, who in 2017 conducted an in-depth investigation into when we began to give little importance to smells, the origins of the myth that smell is an undeveloped and vestigial sense in the human being we owe it to Paul Broca himself, a French brain surgeon and anthropologist of the century XIX. It is he who is credited with having spread the belief that human beings have an underdeveloped olfactory system compared to other species.

In his documents dated 1879, Broca, relying on the fact that the human olfactory area had a smaller volume compared to the rest of the brain, he interpreted this to mean that human beings did not depend as much on smell to survive as other animals did, such as dogs and rodents. Thus, he indicated that this was what gave us free will and that instead of being guided by smells, we made use of our mental capacities, especially our reason.

This statement came to influence great references in psychology, including Sigmund Freud, who went on to state that due to the lack of smell in human beings this made us more prone to mental disorders. This statement is partly correct, but it does not apply to the entire human species. What has been seen is that people with impaired or reduced sense of smell are more prone to psychiatric disordersNot because of the fact that the human species has this "reduced" meaning.

These "findings" and interpretations made both by Broca and Freud and so many other thinkers of the nineteenth century fed even more the belief and ingrained that the sense of smell was not very adaptive and did not serve much in the species human. In the western world there was (and still is) the idea that those who allow themselves to be dominated by smell are letting their animal instinct dominates them, an instinct that is always perceived as something irrational and illogical, thus discrediting even more this sense.

However, modern and cross-cultural scientific evidence denies that we are bad at detecting odors. It is true that, compared to other species, our olfactory bulb is a little smaller, but this smallness is rather relative. This brain structure sends signals to other areas of the brain to help identify odors, and it is actually quite large and similar. in size and number of neurons to that of other mammals that nobody has doubted that they are good at recognizing and being guided by the smells.

The importance of smell

Smell is important, since it plays an important role in choosing food, avoiding harm and deciding who our partner is. In addition to these more “animal” functions, we must add to this that human beings are the only species that use odors for religious purposes (p. ex. incenses in churches), medicinal (p. g., aromatherapy) and aesthetics (p. g., air fresheners and deodorants). Smelling does not seem to be just an individual act, but an interactional one..

We differ from other animals not because we have it atrophied, but because we give it a different use. For example, dogs are capable of differentiating the odors of different urine for territorial and dominance purposes, an ability that in humans is useless. On the other hand, we are able to differentiate between the smells of wine, those of cheese or even between varieties of cocoa and coffee, this being a useful skill that we use to recognize which foods are best for us or have more caloric intake and lipid.

Cross-cultural look

Many studies have tried to deepen the importance of smell by analyzing the wide repertoire of vocabulary that languages may have to encode smells, based on the idea that if a concept, feeling or meaning is important for the human species, several languages must refer to it. That is, if smells are important to humans, more than one language community have to have a wide repertoire in the form of words and grammatical structures to reference them.

When this issue began to be addressed, many studies focused on English, a language in which it was found that it had a very small vocabulary related to odors and their properties. This same dearth of vocabulary about odors was found in other European languages, which made that many were quick to believe that indeed this sense had little weight in the species human.

Language related to odors is more rare in English compared to other perceptual modalities. For example, in this language, words related to vision are 13 times more used than words related to the most common odors. A study in which they analyzed 40,000 words of this language found that there were about 136 times more words related to vision compared to those related to smell.

However, when analyzing the vocabulary of other languages, it was seen that what was found in Europe was not at all extrapolated worldwide. There were many languages in which smells were represented in a great variety of words and, not only that, but there were also languages in which smells and their properties were grammaticalized or used as metaphors.

Each language has a use of frequency and a number of words associated with different smells, with the languages of Africa, the Amazon and Asia having the most words on this sense. Some examples of this are cha'palaa, ǃxóõ, wanzi, yombe, maniq and jahai to say a few, although the languages in which smell is very important reach up to a thousand.

Many of these languages are spoken by hunter-gatherer communities, which makes sense that they have extensive vocabularies related to smell. For them, knowing how to recognize, identify, position and orient themselves based on what they find in nature is essential for their survival. Know how lions smell, how far away a fruit tree is or how areas near your home are aspects of your daily routine and therefore smells are as important as any other modality perceptual.

Loss of smell as a sign of illness

Loss of smell can be synonymous with something wrong with our brain. Yes, it can be due to a problem directly associated with the nose, such as having too much mucus or a sinus infection. but it may also be due to the fact that the brain structure that is responsible for recognizing odors is failing due to disease neurodegenerative.

Smell can deteriorate as part of the aging process and can be a red flag for a possible case of dementia. If a patient indicates that he is feeling that things do not smell the way they used to, doctors should start to worry. The sense of smell should not be treated as inferior, since in the same way as if a person is staying blind or deaf arouses great concern, the fact that she also loses her sense of smell and taste should also scare her.

Among the diseases in which the loss of smell can be found as a symptom of the onset of the pathology we have memory problems and dementias such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's. Loss of the sense of smell has also been seen to predict COVID-19. And even if the patient does not have dementia or any disease, losing the sense of smell can lead to commit more accidents, such as cooking, burning something and starting a fire that you will notice when it is too much late.

What's more, odor loss has been associated with depression and obesity, health conditions that apparently do not seem to be related to the sense of smell. All these pathologies seem to show that yes, the sense of smell is important for most human beings. beyond the “instinctively animal” or as a vestigial sense and that, in fact, has importance at the level of health and Social.

Bibliographic references:

- Majifa, A. (2020). Human Olfaction at the Intersection of Language, Culture, and Biology. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 0(0) 1-13.

- McGann, J. P. (2017). Poor human olfaction is a 19th-century myth. Science 356 (6338), 1-6.