Aristotle's METAPHYSICS

In this lesson from a TEACHER we explain what does it consist of Metaphysics of Aristotle a work that already begins with the following statement: "all men have by nature the desire to know", and at the top of this knowledge, says the stagirite, is the knowledge of the causes and principles of to be.

And this is precisely the object of the first metaphysics or philosophy, the science of "being as being", to find the first and last cause of everything there is. If you want to know more about Aristotle's Metaphysics, keep reading this lesson offered by a PROFESSOR.

Index

- Introduction to the metaphysics of Aristotle

- Aristotle's metaphysics and his critique of Plato's theory of Ideas

- Aristotle's hilemorphic theory

- To be in power and to be in act

- The four causes and the first Aristotelian engine

Introduction to the metaphysics of Aristotle.

This disciple of Plato, first and teacher of Alexander the Great later, tells us about his vision of the metaphysics

. Everything that exists has 10 fundamental elements, divided into two large groups: substance and accidents.In metaphysics, the substance is that which is capable of existing by itself. Accidents in Aristotle's metaphysics are those elements that although accidents change, being does not change. For example, when we move or grow, we change accidents, when the substance dies.

The substance is composed of matter and form, is the union of the two elements. In contrast to Plato who described two separate elements, two different worlds. Although the thought of Aristotle on metaphysics is different from Plato the elements are the same. For Aristotle, objects are the only object or being but with their form and matter.

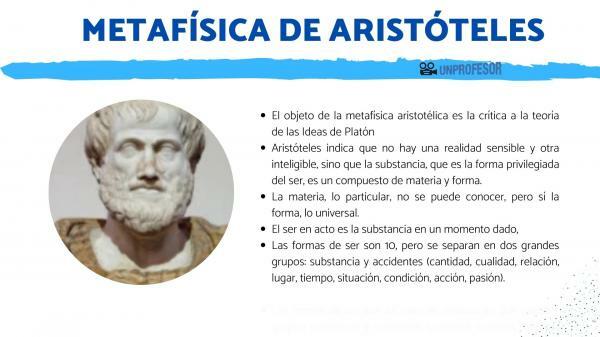

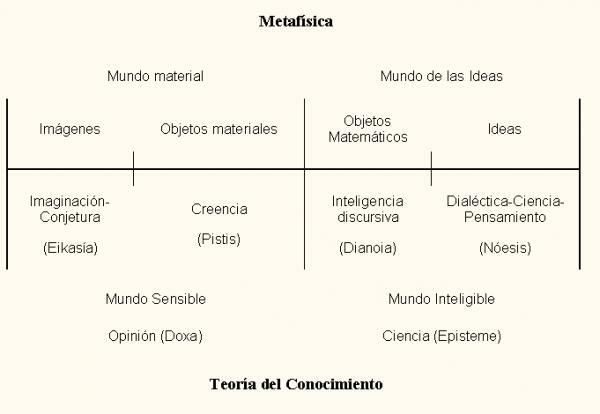

The object of Aristotelian metaphysics is the review to Plato's theory of IdeasSince, despite the fact that Aristotle believes in the existence of universals, he does not consider that these are found outside of things, but within them. You will see that, although Aristotle is contrary to the theory of Ideas, the truth is that the same elements are maintained, but, where Plato speaks of ideas, that of Estagira he will talk in ways.

Likewise, the Platonic division of the world seems unnecessary to him. Duplicating reality is duplicating problems, it makes no sense to suppose that there is another world separate from the physical world where the essences remain. In addition, his mentor was not able to explain the phenomenon of change and movement either.

Aristotle's metaphysics and his critique of Plato's theory of Ideas.

Instead of affirming the existence of two worlds, one material and the other immaterial, Aristotle places these two elements in the substance. There is, then, no sensible reality and no intelligible reality, but substance, which is the privileged form of being, is a composed of matter and form.

The substance is no longer the subject of a copulative sentence, but that which is able to exist by itself. What is interesting is not the structure of language, but the ways of being or categories, which they're 10, but they are separated into two large groups: substance and accidents (quantity, quality, relationship, place, time, situation, condition, action, passion).

Furthermore, the theory of Ideas does not offer an explanation of change and permanence, when its formulation is precisely due to the problem posed by Heraclitus and Parmenides. Aristotle's opposition is based on the inmutability of ideas, which would also imply the immutability of physical objects or copies of them, when in fact, this is not the case.

Aristotle will answer the question of movement with his theory of power and the act, also giving an explanation of why the phenomenon. Every effect has its cause, says the philosopher, and to explain reality exactly four are needed (material, formal, efficient and final).

Aristotle's hilemorphic theory.

The privileged form of being, which is said in many ways, is the substance, which is defined by Plato's disciple as everything that does not need anything else to exist. This substance, which is the individual, nature, things, is a compound of matter (particular) and form (universal). Matter is passive and form is what updates it. The Aristotelian form, unlike Plato's essence, is not found outside of things, but In the things.

On the other hand, they are the accidents of the substance, which occur in it and cannot exist outside of it. Substance is one of the categories of being, along with accidents, that belong to the first. The different categories of being, make being what it is, and change, without ceasing to be what it is.

Example: a change of place constitutes an accidental change, which does not make the thing stop being what it is. On the contrary, death or birth is a substantial change, and this does suppose a modification of being.

Aristotle says:

"Being in itself has as many meanings as there are categories, because as many as distinguish, as many are the meanings given to being."

Being Aristotelian is only one, but admits different meanings. All forms of being refer to the substance, which ensures the unity of being. The first substance is the concrete thing and the second substance constitutes the essence.

“Substance is said of simple bodies, such as earth, fire, water, and all similar things; and in general, of the bodies, as well as of the animals, of the divine beings that have bodies and of the parts of these bodies. All these things are called substances, because they are not the attributes of a subject, but they are themselves subjects of other beings ”.

Matter, the particular, cannot be known, but yes the form, the universal. Matter is the way of being that makes the object what it is and not something else and is passive. But the form, which is active, constitutes the very nature of being and is universal. Thus, it shapes matter and as natural, it is the cause of motion. The problem can, in this way, be explained from the substance.

To be in power and to be in act.

Parmenides claimed that movement or change (in ancient Greece the same term was used for both), could not exist, since it is not possible to pass from non-being to being. Plato, with his theory of Ideas, did not know how to answer this problem, but Aristotle did, who defines the movement What the passage of a relative non-being, what would be the potential being, being in act.

"Being is not only taken in the sense of substance, of quality, of quantity, but there is also being in potential and being in act, being relative to action."

Being in act is the substance at a given moment, as it is presented to the individual and as it is known. Being in power refers to the ability to become, to be able to be something other than what one is, to change. Example: a seed can become a tree, therefore, the seed, in fact, is a potential tree, and this, the actualization of that potential.

The four causes and the first Aristotelian engine.

In Book I of Metaphysics, Aristotle exposes his theory of the four causes of being, that he had already dealt with in Physics. The first two causes are intrinsic and the other two, extrinsic to being.

Material cause

It is what determines what an object is what it is, its appearance. Example: the wood of a table.

Formal cause

It is that which identifies the thing, that which is always the same. Example: the design of the table (that is, a four-legged piece of furniture, in this case made of wood, but it could be made of another material, which fulfills a certain function)

Efficient cause

It is the agent of change or movement, which interacts with things by giving them movement. Example: the carpenter who modifies the wood, shaping it to make it what it is.

Final cause

He constitutes the finality of being and Aristotle assures him that he is "an immortal, immutable being, ultimately responsible for all fullness and order in the sensible world." The Aristotelian god is pure entelechy, he can only think of himself, but influences natural beings is by "aspiration or desire" to imitate him. He is the first immobile engine of the universe.

If you want to read more articles similar to Aristotle's metaphysics, we recommend that you enter our category of Philosophy.

Bibliography

- Aristotle. Metaphysics. Ed. Austral. 2013

- Reale, G. Aristotle's "Metaphysics" reading guide. Ed. Herder. 1999