Romanesque art: its origin and characteristics

If we talk about Romanesque art, surely we will all be quite clear about which period we are referring to. Indeed, it is one of the best-known artistic styles of the Middle Ages, generally presented in opposition to the Gothic. Surely, in many manuals you will have seen the Romanesque identified with a certain intellectual darkness and with a poor and rural Europe; On the contrary, the Gothic is related, without exception, to the awakening of the cities, the bourgeoisie and medieval humanism.

This generalization is not without reason, of course; however, and as always, you should not get completely carried away by the topics. Because despite the fact that, indeed, the Romanesque is the son of feudalism, it is no less true that the full Romanesque coincides with the rise of cities and medieval scholasticism and that, in fact, the first and most important cathedrals in Europe were built in this style. Some examples are the cathedrals of Pisa and Verona, in Italy, those of Santiago de Compostela and Lisbon on the Iberian Peninsula, that of Bamberg in Germany and that of Arles, in France.

What do we know, then, of Romanesque art? And, above all, what do we call Romanesque art? What are the characteristics of this artistic style? Is the Romanesque a unique style, or, on the contrary, does it present significant differences depending on the region and the historical moment? We propose a trip to the birth and gestation of the Romanesque; a journey in which, in addition to offering an overview, we will try to shed light on some of the most frequent and widespread topics of this style of the Middle Ages.

- Related article: "The 3 phases of the Middle Ages (characteristics and most important events)"

Romanesque art was not always called Romanesque

Indeed, the artists of the Middle Ages who built the Romanesque churches and monasteries did not call themselves Romanesque artists. In fact, the vast majority of artistic denominations appeared much later than the style or period to which they refer, and not always in an appreciative way.

Medieval art, so reviled for centuries, began to recover the interest of scholars in the 19th century. It was in this century when the word Romanesque was coined to refer to the art of the first centuries of the Middle Ages. The term emphasizes the late Roman and "decadent" solutions that this medieval style was believed to use.; that is to say, the word Romanesque was used in a derogatory sense.

William Gunn, an art historian, was the first to use the term in 1819. He called the buildings of this era Romanesque Architecture; a little later, in 1830, Arcisse de Caumont referred to this style as roman, making a clear parallelism between the Romanesque, which, according to him, comes from Roman art, and the Romance languages, which derive from Latin.

This Arcisse was right; In fact, although the Romanesque is a common artistic expression throughout Europe, each region presents some specific peculiarities, just like every vernacular language is an interpretation of the mother tongue, Latin.

Let's see, first, what is the periodization and context of this style. Then, we will comment on the general characteristics of Romanesque art and, finally, we will stop to analyze the geographical characteristics of this style.

- You may be interested in: "How to distinguish the Romanesque from the Gothic: its 4 main differences"

The stages of the Romanesque

Traditionally, art historians have distinguished three stages in the evolution of the Romanesque style: the first Romanesque (10th-11th centuries), the full Romanesque (11th-12th centuries) and the late Romanesque or late Romanesque (12th-13th centuries). However, and as always when we talk about historical periods, this separation is generic and conventional, with the only objective of facilitating the study of the Romanesque, since this periodization is not fulfilled in all parts of Europe in the same way. manner. For example, in the Holy Roman-Germanic Empire the periodization of the first Romanesque coincides with the called Ottonian art, very characteristic of the time and of the region, and which presents important differences.

The so-called full Romanesque can be considered a common style in Europe (despite the regional peculiarities that we have commented on in the first section). This style spread throughout Europe during the 11th and 12th centuries, spurred on by a series of very specific historical and social circumstances, which we will point out below.

The Gregorian reform and the unity of the rite

The reform of the Church carried out by Pope Gregory VII in the 11th century greatly influenced the expansion of this more or less homogeneous European style. Among other things, because The Gregorian reform supposes the unification of the Catholic liturgy in all the territories; that is, from that moment on, all European churches must follow the Roman rite in their liturgies. The temples have to adapt, therefore, to this homogenization, a fact that facilitates the appearance of buildings with very similar and specific characteristics.

The feeling of Christian unity: pilgrimages and the Crusades

During the centuries of the full Romanesque, an unprecedented feeling of spiritual unity arose in Europe. The roads are filled with pilgrims who spread the news from city to city. The devotion towards the relics of the saints grows without stopping; in fact, for an altar to be consecrated, it is necessary that it house a holy relic. As a result of this devotional fever, new temples are erected in all corners of the continent, most built in this new style that is spreading throughout Europe.

The First Crusade reactivates the roads to the East and promotes a religious feeling that unifies all Europeans; It will be this feeling that, in the end, reinforces a unique artistic expression. In addition, the Crusaders return from the Holy Land with sacred relics and Byzantine works of art, which have special relevance in the configuration of Romanesque art.

Thus, as we will see later, the Byzantine icons, which show hieratic and flat figures on wood, would have a great influence on Romanesque painting. For their part, the mosaics of the Byzantine East would greatly impact the art of northern Italy; Saint Mark's Cathedral in Venice is a typical example of this Italian “orientalizing” Romanesque.

- Related article: "5 topics about the Middle Ages that we must get out of our heads"

Universities and the exchange of knowledge

Contemporary to this world of exacerbated religiosity, we find the first universities, emerged in the shelter of the increasingly flourishing cities. These centers of knowledge attract students from all over Europe, and this incessant flow of intellectuals who exchange knowledge will also have a lot to do with the transmission of the artistic novelties of the moment.

Cluny Abbey and its expansion throughout Europe

The Cluny abbey, in the Burgundy region, was founded in 910, and soon it becomes the epicenter of an enormous network of monasteries that extends throughout Europe. Until then, European monasticism was characterized by a great dispersion. Cluny will be, in this sense, a great agglutinator of monastic buildings (more than 1000 in all of Europe) that, in the end, will lead to a stylistic unification that will spread throughout the continent.

But what are these characteristics that spread throughout Europe and that make up the so-called full Romanesque? Let's see them below.

General characteristics of Romanesque art

As a style present throughout medieval Europe in the 11th and 12th centuries, the full Romanesque presents some specific characteristics. Before dwelling on the peculiarities of each region, we are going to briefly review what these general characteristics of the European Romanesque are.

romanesque architecture

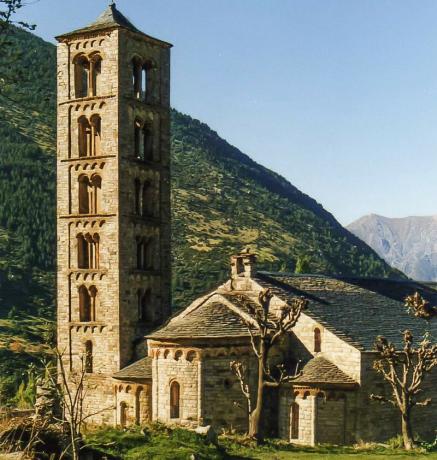

The building par excellence in Romanesque art is, of course, the church. The building usually has a basilica or Latin cross plan, and presents, on its eastern side, a semicircular or straight apse and, on the western part, an entrance portico to the church. Attached to the building we find the bell tower; The most usual is that there are two (framing the main western façade), but we also find examples with a single tower (for example, the churches of the Bohí Valley, in Catalonia). Another common type of bell tower in the Romanesque is the belfry, a wall that stands out vertically from the rest of the building and in which there are openings where the bells are sheltered.

The most common cover in Romanesque constructions is the barrel vault with transverse arches and exterior buttresses, but we can also find semicircular or pointed vaults. In fact, it is a mistake to associate this type of pointed arch only with the Gothic, since we find quite a few Romanesque buildings that use this solution; among them, the paradigmatic church of the abbey of Cluny. Another of the vaults used by the Romanesque is the groin vault, which is formed with the confluence of two barrel vaults.

In monasteries, the most important element is the cloister, open space from where the monastic rooms are articulated. In each of the pandas or sides of the cloister we find capitals where sculpture abounds, with great iconographic diversity: from religious and biblical scenes to elements of plant or animal decoration, including figures from the medieval bestiary and decoration geometric.

During the full Romanesque, the era of pilgrimages par excellence, pilgrimage churches make an appearance. This type of building adds the ambulatory, that is, the ambulatory or corridor that surrounds the back of the presbytery. This new Romanesque element makes it easier not only for pilgrims to move around the main altar while the liturgy is being celebrated, but also which also allows several masses to be celebrated at the same time, since the apses open onto the ambulatory, small apses arranged in a battery.

- You may be interested in: "What are the 7 Fine Arts? A summary of its characteristics"

romanesque sculpture

In the Romanesque churches an authentic iconographic program unfolds, which is concentrated in the portals and in the cloisters. On the facades of the churches, the sculpture is found mostly in the tympanum and in the archivolts. Romanesque sculpture is subject to architecture, so the shapes adapt to the space and the shape of the building. The iconographic program usually revolves around the Divinity, surrounded by the mandorla or almond; that is to say, the figure of Christ as judge, the so-called Pantokrator.

Around it, it is very common to find the Tetramorphs, that is, the representation of the four evangelists: the eagle for Saint John, the angel for Saint Matthew, the ox for Saint Luke and the lion for Saint Frames. A fairly recurring iconography is the Virgin Theotokos, or the Virgin as mother of God, a figure that comes directly from the Byzantine world.

Both in Romanesque sculpture and painting we find a beleaguered conventionalism in the resolution of the figures. The images are stereotyped and offer little freedom of innovation (although, in reality, each artist is different). Let's remember that in the Middle Ages it was not important how it was represented, but what was represented. Medieval plastic art is an eminently conceptual art; it captures transcendent realities, not tangible realities. For this reason, both in sculpture and in painting, the concepts of space-time are suppressed; the represented world is beyond the reality that surrounds us.

romanesque painting

In the Romanesque, we find three main forms of pictorial manifestation: mural painting, panel painting and mosaic.

We have already commented that the latter drinks directly from the models of Late Antiquity, as well as from the world Byzantine, and is present, above all, in the Romanesque of the Italian Peninsula, especially in the Veneto area and in Sicily. For its part, panel painting abounds with altar fronts and altarpieces (from the Latin retro-tabulum, literally, behind the altar table).

As for mural painting, perhaps the best-known typology of Romanesque art, we can clearly distinguish two techniques: tempera and fresco painting. While the first technique offers poor preservation, since the pigment only adheres to the surface, the second guarantees a greater durability, since the fresco technique allows the wall to absorb the pigments and, in this way, the paint is integrated into the Wall. But, precisely for this reason, fresco is a much more complicated technique, since, to guarantee this absorption, the artist had to work on the still damp wall. This, obviously, slowed down the process, since during each working day it was only possible to paint on a specific part of the wall.

The main Romanesque pictorial iconography was found in the apse, which was, of course, the most important part of the church. But this does not mean that we should think that the rest of the walls were bare. Quite the contrary; The entire building was polychrome (exposed stone is another of the topics of the Middle Ages). The iconographic program dealt, once again, with Christ the judge, represented as the light of the world (Ego sum lux mundi), and with the Virgin in Majesty as the mother of God (two of the best examples are the Pantokrator of San Clemente de Taüll and the Virgin in Majesty of Santa María de Taüll). Likewise, there is no room for realistic representation; concepts are embodied, which are articulated by horizontal bands. The figures show representative conventions and stereotyped models, and the colors are flat and intense, with a clear influence from the Mozarabic codices.

The "Romanesque" of Europe

We have already discussed it in the introduction; Despite the fact that full Romanesque is a fairly homogeneous style, each region presents its particularities. Let's see, quickly, what these characteristics are.

Italy

The most recognizable feature of the Romanesque in Italy is the inclusion of the campanile or free-standing tower, that is, not attached to the church. In the same way, the baptistery stands apart, as a building with its own personality. The Pisan complex is a magnificent example of this Italian typology.

In the Tuscan Romanesque in particular, the buildings present marked bichrome in the materials. Finally, we can highlight the enormous Byzantine influence that the Romanesque of Veneto presents (like the one already aforementioned Cathedral of San Marcos in Venice), as well as in Sicily, which also shows Arab and norman.

France

In France, of course, The example of the Burgundian monastery of Cluny prevails which, as we have already mentioned, exports its monastery model to the rest of Europe. In addition, in the French and Burgundian portals we find a great monumentality in the figures, as witnessed by the portal of San Pedro de Moissac.

Holy Roman German Empire

In the Germanic part of the Empire, Romanesque buildings present a very marked verticality. In addition, its powerful and thick walls give the sacred buildings the appearance of fortresses, which is accentuated by the scant ornamentation.

The area of the Aragonese and Catalan Pyrenees

In the Pyrenees area we find an evident Lombard influence, as well as elements from Cluny. Also characteristic of these churches is the unique bell tower attached to the temple.

Camino de Santiago, Castile and Navarre

The marked role that Cluny had on the Camino de Santiago is reflected in the stylistic influence that this monastery exerted on the buildings in the area. They were Alfonso VI of León and Constanza of Burgundy (his wife, who came precisely from the duchy where Cluny was located) those who spread the Cluniac precepts throughout the kingdom, through the founding of monasteries for the resettlement.