The 10 most important Baroque paintings

The Baroque is an era and an artistic current that occurred, mainly, in the 17th century. This artistic style has numerous masterpieces, distributed among the best museums in the world.

In this article we will focus on baroque painting and we will rescue 10 of his most important paintings.

- Related article: "What are the 7 Fine Arts? A summary of its characteristics"

Baroque painting

The 17th century witnessed the rise of true masters of painting. Artists like Velázquez, Vermeer, Rubens or Ribera filled the pages of art history in numerous ways. masterpieces, essential to know both this historical period and the evolution of art in general.

As with most art movements, the Baroque is not a single style.. In each region and each country it had its own characteristics, driven by its own economic, religious and social context. Thus, while in Catholic countries this style served as a vehicle for the Counter-Reformation, in the regions Protestants became much more intimate and personal, since it was promoted by the merchants and bourgeois of the cities.

- You may be interested in: "The 4 most important characteristics of the Baroque"

The 10 main paintings of the Baroque

Next, we will take a short trip through the 10 most important Baroque paintings.

1. Las Meninas, by Diego Velázquez (Museo del Prado, Madrid)

It is probably one of the most reproduced pictorial works and one of the most famous in the world. The canvas is known as Las Meninas, although its original name was The family of Felipe IV. It is, without a doubt, one of the masterpieces of baroque painting and art history in general.

It was painted in 1656 in the Cuarto del Príncipe del Alcázar in Madrid, and it recreates an amazing game of light and perspective. In the background, reflected in a mirror, we see the busts of the monarchs, King Felipe IV and his wife Mariana of Austria. To the left of the canvas, Velázquez takes a self-portrait at the easel. Interpretations of the work have been and continue to be highly varied. He is painting the kings, and suddenly he is interrupted by the little infanta Margarita, who is accompanied by her meninas and her entourage? Be that as it may, the painting fully immerses the viewer in the scene, as if he were one more character in it.

2. Judith and Holofernes, by Artemisia Gentileschi (Uffizi Gallery, Florence)

For some years now, the extraordinary work of Artemisia Gentileschi has been recovering the place it deserves in the history of painting. Judith and Holofernes is one of the masterpieces not only of her pictorial corpus, but of baroque painting in general.

The artist represents us the moment, recorded in the Bible, in which Judith, the Jewish heroine, beheads Holofernes, a Babylonian general who wants her. Artemisia represents the moment with a ferocity that freezes your breath. Many critics have wanted to see in the crudeness of this painting all the rage and suffering that the rape of which she was the victim shortly before the execution of the first version of the painting, preserved in the Museum of Capodimonte, Naples. In any case, the wonderful chiaroscuro, the composition and the dynamism of the characters make this work one of the best samples of Baroque painting.

- Related article: "The 7 best museums in Spain that you cannot miss"

3. Girl reading a letter in front of the open window, by Johannes Vermeer (Alte Meister, Dresden)

The great and, at the same time, intimate pictorial universe of Vermeer is reduced, unfortunately, to around thirty recognized works. This scarcity of artistic production turns this Dutch Baroque artist into a painter surrounded by a halo of mystery. Its interiors were tremendously valued at the time, although they later fell into oblivion and were not claimed until much later by the 19th century impressionists.

The work that concerns us perfectly represents that universe of domestic intimacy characteristic of the painter. In a room illuminated by the milky light that enters through an open window, a young woman is concentrating on reading a letter. Her private world becomes more inaccessible because we cannot physically reach it, since the table and the curtain in the foreground prevent us from doing so. This canvas is a beautiful example of baroque painting from the Netherlands and, above all, of that world of elusive and almost ghostly characters that populate the work of this extraordinary artist.

- You may be interested in: "Differences between the Renaissance and the Baroque: how to tell them apart"

4. Still life, by Clara Peeters (Prado Museum, Madrid)

The genre of still lifes has not been highly regarded in the history of art, despite the fact that it is of a genre that requires great detail and, of course, an indisputable ability to capture textures and surfaces. A masterpiece of the genre is, without a doubt, this Still life of the painter Clara Peeters.

In it, the artist's virtuosity is not only evident in the careful representation of the elements, but in the series of self-portraits that the painter made, as a reflection, in the jug and in the cup. Capturing a reflection on a surface was something that required exquisite virtuosity, and Clara records her pictorial ability through this resource, as well as being a way to vindicate his role as an artist in a profession dominated by men.

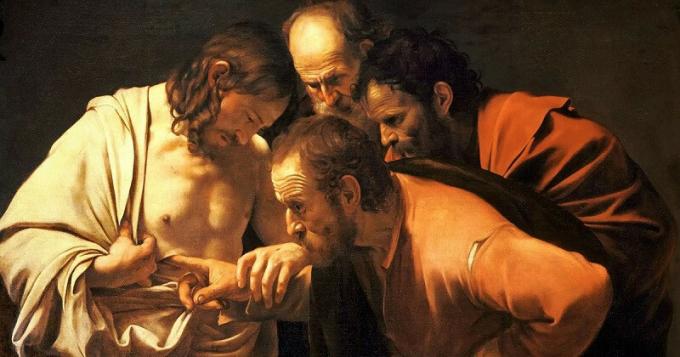

5. The incredulity of Saint Thomas, by Caravaggio (Schloss Sanssouci, Potsdam)

The biblical theme of the doubt of the saint before the resurrection of Christ is collected in this work with an impressive naturalism. Saint Thomas is inserting a finger into the wound that Jesus looks on one of his sides. Christ himself guides his hand, encouraging him to believe through physical evidence what he has not believed through faith. This scene had never been seen told with so much, we could say, crudeness. The characteristic realism of Caravaggio is evident in the anatomy of the bodies, in the wrinkles that furrow the foreheads of the apostles, in the dirty nails that Saint Thomas himself presents and, above all, in the tip of his finger introducing himself into the flesh of Christ. Caravaggio's work is one of the best examples that the Baroque is not only theatricality and pomp, but also often approaches reality with surprising naturalism.

- Related article: "Is there an art objectively better than another?"

6. crucified christ, by José de Ribera (Diocesan Museum of Sacred Art, Vitoria-Gasteiz)

One of the most impressive crucified of baroque painting. It is preserved in the Diocesan Museum of Sacred Art of Vitoria-Gasteiz, from the disappeared convent of Santo Domingo, and is considered one of the best representations of Christ crucified in painting. Spanish. Against a neutral and markedly dark background, which reinforces the idea of the biblical eclipse that accompanied the death of Christ, the figure of Jesus rises on the cross, with the white body and contorted in a forced contrapposto. The only source of light is his body, since even the purity cloth is of a similar hue to the wood of the cross to which it is nailed. The scene seems to capture the moment when Christ looks up to heaven and murmurs: “Everything is over. Consumatum est”.

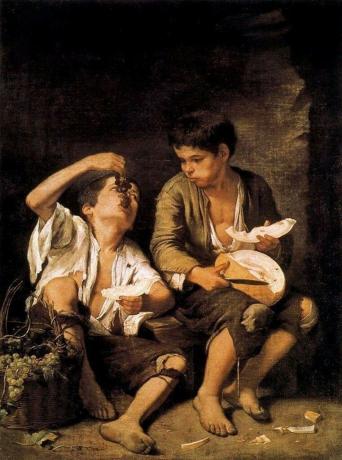

7. Children eating grapes and melon, by Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (Alte Pinakothek, Munich)

We have already commented that realism is also typical of Baroque art. A good example of this is this marvelous canvas by the painter Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, kept in Munich, which represents two poorly dressed children eating grapes and melon. The Spain of the 17th century offered marked contrasts, and poverty was a common sight in the streets of cities like Madrid. On this occasion, Murillo represents the two boys concentrating on his food. They are not looking at the viewer; in reality, they hardly notice our presence. While they devour the melon and grapes (perhaps one of the few foods they will have access to for many days), they talk calmly, as witnessed by their exchanged glances. Dirty bare feet and threadbare clothes add a dramatic note to the endearing scene.

8. Vault with the Apotheosis of the Spanish monarchy, by Luca Giordano (Prado Museum, Madrid)

This fantastic ceiling, made at the end of the 17th century using the false fresco technique, can currently be seen in the Library of the Prado Museum in Madrid. Originally the vault belonged to the old Hall of Ambassadors of the Buen Retiro Palace, a place of rest and leisure that the Count-Duke of Olivares ordered to be built for King Felipe IV.

As its name indicates, the Hall of Ambassadors was the reception place for the monarch, so the iconography displayed on its ceiling is an exaltation of the Hispanic monarchy. Giordano creates an extraordinary composition, dotted with allegories and symbols drawn from mythology. that sought to highlight the antiquity of the Spanish crown and its preeminence over the other royal houses European.

9. the three thanks, by Rubens (Prado Museum, Madrid)

Apparently, Rubens made this canvas, one of the most famous of his oeuvres, for his own enjoyment, as evidenced by the fact that, at his death, it was among his personal collection. In fact, the features of the woman on the left are very similar to those of his second wife, Helena Fourment, whom Rubens married when she was only sixteen and he, fifty- three. Since ancient times, It is usual to find the reason for the Graces related to betrothals, so it does not seem unreasonable to assume that the artist painted the painting as a tribute to his own marriage. The three figures stand voluptuously and join their hands in what appears to be some kind of dance. It is indeed one of the artist's most elegant and sensual paintings.

10. penitent magdalene of the lamp, by Georges de La Tour (Louvre Museum, Paris)

De La Tour is a fantastic painter who is famous for the exquisite chiaroscuro in his compositions, achieved by the glow of one or more candles.

In this case, the painting shows us a Mary Magdalene absorbed in her meditation. Her gaze is fixed on the fire of the candle that burns before her, the only source of light in the painting, as is usual in the artist's work. The saint supports her head in one hand, while in the other, which rests on her lap, she holds a skull, a symbol of penance and the transience of life, so typical of the Baroque. The penitent Magdalene motif was very common in the 17th century. De La Tour himself made up to five versions of this painting. In two of them, the skull is on the table, and with its volume it hides the fire of the candle, which further accentuates the chiaroscuro of the scene.