The 3 medieval estates: origin, history and characteristics

On August 4, 1789, the estate society was abolished in France. A new era was born and, in this way, the medieval estates, which had been the pillar of society for centuries, were abandoned. A class society that was seen then, in the midst of the Revolution, as something archaic and obsolete that needed to be suppressed.

However, is everything that is told about the medieval estates true? Is it true that the medieval estates were something rigid and lacking in flexibility? Let's remember that the Middle Ages is a period of 10 centuries, during which many changes took place and different realities occurred. Although it is true that the general hierarchy (the one that divided society into three estates) was maintained until Well into the 19th century, it is no less true that this division suffered some ups and downs depending on the context of the moment.

Let us see, then, what were the estates in the Middle Ages, their origin and their characteristics.

- Related article: "The 15 branches of History: what they are and what they study"

What is a statement?

First of all, it is necessary to clarify this concept. The RAE defines estate as "a stratum of a society, defined by a common lifestyle or similar social function." And, specifically, it refers to the social strata that constituted the bases of the Old Regime, that is, of society before the French Revolution and the Industrial Revolution.

The difference between an estate society and a class society is that, while in the latter there is a certain permeability based on the economic capacities of the individual, the first is more or less closed to changes, and the members of each estate belong to it by ties of blood. It is from this perspective that we must understand society in the Middle Ages, as an eminently hierarchical system in which each person belonged to a specific class and from which, most likely, they could never go out.

- You may be interested in: "The 5 ages of History (and their characteristics)"

Origin of the medieval estates

As we have already said, the social hierarchy in the Middle Ages was based on three very different estates: the nobility, the clergy and the so-called third estate (the rest of the population). Despite representing only 10% of the total, the first two groups had special privileges, among which were the monopoly of power and the exemption in the payment of taxes. But where did this division come from?

The Indo-European world

This tripartite society is not something unique to the Middle Ages; in fact, It has its roots in the Indo-European cultures that, several millennia ago, populated Europe and part of Asia. These cultures were composed of three groups: the rulers, the warriors, and the producers. Many of the European and Asian cultures come from these tribes; In the extensive Indo-European family tree we find the Germanic, Greek, Slavic and Latin peoples, as well as the millenary culture of India. In fact, the caste system, which is still more or less in force today, is the direct heir to this strict hierarchy.

- Related article: "Indo-Europeans: history and characteristics of this Prehistoric people"

Plato's ideal city and his influence in the Middle Ages

Already in classical Greece, Plato (s. Live. C) collects this division in his work The Republic, when he affirms that the ideal society must be made up of three social groups: those who govern (who must own the gift of wisdom), those who fight (who must be strong) and the craftsmen who work (who must enjoy temperance). According to the Greek philosopher, only in this way can it be guaranteed that society flows harmoniously towards a common good.

This Platonic concept is collected by St. Augustine, already in the Christian era, in his work The City of God, where he holds that the earthly city, the pale reflection of the heavenly city, must be composed of these 3 groups social. Only with the harmony of these 3 estates can the order of the cosmos created by God be given. There is a document where the class division of the Middle Ages is clearly expressed, and it has gone down in history as a statement cultural: and it is the poem that Aldebarón de Laón, French canon, sent to Robert II of France, where he quotes the 3 estates and calls them, literally, speakers (those who pray), bellatores (those who go to war) and labradors (those who work).

This division is the one that, in general, can be applied to the entire Middle Ages; although, as we will see below, with some nuances.

- You may be interested in: "Anthropology: what is it and what is the history of this scientific discipline"

The medieval estates

These are the main characteristics of the estates of the Middle Ages.

The noble estate and the establishment of the feudal regime

The political system of the Germanic tribes that entered the Roman Empire, basically formed by a king and his knight advisers, merged with the concept of State that still prevailed in the territory Roman.

So, the early Germanic kingdoms still maintained a network of civil service or public servants. For example, in the Carolingian Empire, the territory was divided into counties, where a come or count exercised authority on behalf of the king. Over the years, these counts or public delegates settled permanently in the assigned territory, which became part of his personal patrimony, especially from the capitulations of Querzy (877), where the hereditary system of transmission of land. In short, in Europe the concept of state was forgotten, and all its territories fell into the hands of lords who were, in reality, the owners of said lands.

lords and peasants

The old Carolingian aristocracy, made up of those closest to the king, gave rise to the noble class. The nobility was exempt from paying taxes and, together with the knights, formed the group of bellatores mentioned by Aldebarón in his poem.

The noble class had direct domination of the land. And, when we say of the earth, we also refer to the human force that it contained. In effect, the lords were the effective owners of the land and, as such, collected rents from their inhabitants. The fiefs (the parcels of land that corresponded to a lord) were complete and self-sufficient units, and were made up of the seigneurial reserve (the so-called terra indominicata) and the meek. The seigneurial reserve was reserved for the lord, and the serf had the obligation to work it.

On the other hand, the meek were the plots that were granted in usufruct to the serfs to guarantee their own subsistence. In addition, there were a multitude of resources and assets (forests, bridges, mills...) that were, in effect, the property of the lord, so he could establish a use tax if he so wanted.

lords and vassals

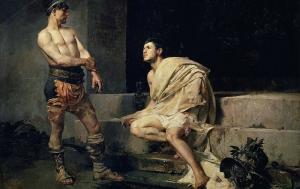

The basis of the feudal system is the vassalage networks. Without them we cannot understand medieval society, since there were very complex ties of fidelity within the noble class. The main components of the vassalage system are the lord and the vassal; the former generally belonged to the nobility, while the latter was simply a knight. However, this was not always the case, and these ties were so complex that sometimes we find kings who are vassals of counts.

The relationship between lords and vassals implied a series of obligations: first, an absolute fidelity between both contracting parties and, second, the obligation of the vassal to offer auxilium and consilium, that is, help in case of war and advice. In exchange, the lord granted his vassal a set of lands and the income they brought him. These lands are what we call a fief, and it is the basis of feudal society, which reached its zenith during the 11th and 13th centuries.

2. Church

During the feudal era, the clergy constituted one more feudal lord. Multitude of lands were owned by monasteries and abbeys, so the abbots exercised the same functions as the nobles.

Do not confuse, however, the ecclesiastical establishment with the origin of its members. The estate as such enjoyed certain privileges (just like the nobility), but not all its members came from the upper estates. It was not the same, for example, to be a bishop than a monk in a humble abbey. Thus, we clearly distinguish a high clergy, made up of members from the high nobility (and even from the royal family) and a lower clergy, made up of a more or less well-to-do peasantry, artisans and other workers.

Belonging to the ecclesiastical establishment in the Middle Ages had, of course, many advantages. To begin with, for many centuries it was practically the only access to culture, since the monasteries had been erected as temples of learning and knowledge.

- Related article: "5 topics about the Middle Ages that we must get out of our heads"

3. The third estate and the cities

After the fall of the Roman Empire, the cities went into frank decline, and ceased to be the seat of local government to simply become places of residence for the bishop. During the first centuries of the Middle Ages, Europe became rural and, in this way, the village, assigned to a fief or manor, acquired great importance.

Gradually, and with the economic prosperity that began to be perceived from the 11th century, the cities or boroughs began to acquire new strength and importance. There are more and more agreements with the lords, which are translated into municipal privileges. From now on, The public power of the city is being configured, and the municipal government bodies are born.

The oligarchy of cities: merchants and urban nobles

In this climate of economic prosperity, merchants are beginning to crystallize as a booming group. This social group, exclusive to the cities, is the one that will give rise to the bourgeois class, which will acquire more and more influence and power. For their part, bankers intensify their activity, freed from the bondage implied by the sin of usury (harshly condemned by the Church in previous centuries).

These bourgeois will be the ones who will make up, along with the nobles who settle in the city, the urban oligarchy. This oligarchy will possess the monopoly of municipal power and will enter into constant conflict with the so-called “minute popolo” or “small town”, always away from power. Thus, we see that, at the end of the Middle Ages, the third state "opens up", branches out, and configures what, later, will be the society of the modern age.

craftsmen and students

This “small town” is made up of a completely heterogeneous mass of population. Craftsmen, students, friars; the majority in perpetual struggle against that citizen oligarchy that exercises the same abuses of power that in the past had been exercised by the lords in rural Europe.

In effect, attracted by economic growth and the increasingly high demand for products, rural artisans emigrate to the cities, and begin to group into guilds. These guilds are the ones that regulate the trades; the trade union jury is even the one that renders the verdict when deciding whether an official craftsman can be promoted to master.

The birth of the universities in the 12th and 13th centuries brought rivers of students to the towns. These students, mostly very young, are the protagonists of not a few fights and skirmishes against the municipal power (as we can see, things have not changed much since then). It should also be noted that the influx of both students and passing merchants leads to a significant growth in prostitution, taverns and gambling houses.

Finally, we cannot forget the marginalized: sick, “crazy”, beggars; beings that live outside of order and social laws, and that are increasingly numerous in cities in full expansion and growth. Often, hospitals, lazarettos and houses of charity (which, on the other hand, abound in medieval cities) are not enough to cover the needs of these poor people, and they are pushed to delinquency and crime.

The Middle Ages are a much more complex time than is believed, but we hope that this brief review of the medieval estates will help you to better understand both its social structure and its contradictions internal.