Could Neanderthals speak?

They became extinct approximately 30,000 years ago and lived alongside modern humans for ten centuries. Since the first evidence of these relatives was found near Düsseldorf in 1856 close, Neanderthal man has been one of the most studied questions of evolution human.

Many are the questions that, throughout all these years of study, have been formulated about the Neanderthals. One of these questions, which has baffled scientists in recent decades, is Whether or not Neanderthals were able to speak. The extraordinary resemblance of these men and women to us is evident; but there was a piece of the evolutionary puzzle that resisted being deciphered. Now, a recent investigation seems to have found the answer.

Could Neanderthals speak? New discoveries

It is estimated that Neanderthals arose on the European continent about 300,000 years ago. They descend from the so-called Homo Heidelbergensis, the first human species that spread to many regions of the world.

It is estimated that, during the second ice age (Mindel Ice Age, about 400,000 years ago), the

heidelbergensis they sought protection from the extreme cold in southern Europe, where they were isolated and generated new species such as Neanderthals. So, Neanderthals can be considered the first human species originating from Europe.Currently, genetic studies have been able to find out that Sapiens and Neanderthals were much more closely related than previously believed. In fact, thanks to DNA analysis, it has been possible to verify that, around 300,000 years ago, the hybridization of both took place. species, which would explain that, currently, a large part of the non-African population present in its DNA genome neanderthal.

So how alike are we? Both species mated and produced fertile individuals (unlike other animal hybridizations), which seems to indicate that both species were genetically very close. Let's examine these similarities in more depth.

- Related article: "What are hominids?"

Our closest relatives

Remarkably similar to us, Neanderthal men and women nevertheless had a much larger complexion than Sapiens. Thus, they had a large thoracic capacity and a large and heavy bone structure; the weight of an adult could reach 70 kilograms and be around 165 centimeters in height.

Recent studies have been more detailed and maintain that the majority were red-haired and light-skinned, to absorb solar radiation to the maximum, much scarcer in northern Europe than in Africa. This data was discovered by Carles Lalueza-Fox, from the University of Barcelona, who found a mutation in the MC1R gene, from fossil material from two Neanderthal sites, one from Asturias and the other from Italy.

On the other hand, the cranial capacity of these relatives was somewhat larger than ours: while that of the modern human being is around 1,200 cm3, that of the Neanderthals reached the figure of 1,550, something that, a priori, could make us question whether the level of intelligence of these "cousins" was superior to ours.

So were Neanderthals smarter than Sapiens? Does the greater cranial capacity have something to do with the ability to emit sounds and express oneself with a more or less articulate language? In a word: could Neanderthals speak?

- You may be interested in: "The Theory of Biological Evolution: what it is and what it explains"

The problem: the vocal organs do not fossilize

The size of the skull does not necessarily indicate greater linguistic abilities; however, skeletal remains have revealed that Neanderthal cranial areas that house language-related brain areas are very similar to those of modern humans. Would this be the definitive indication?

There is a problem regarding the study of language in extinct species, and that is that the organs related to speech (the larynx, the tongue, the glottis and the vocal cords) do not fossilize. This means that, in the Neanderthal remains that have been found, there are not and could never be elements that would give us a clue about the capacity for oral expression of our relatives. How to study it, then?

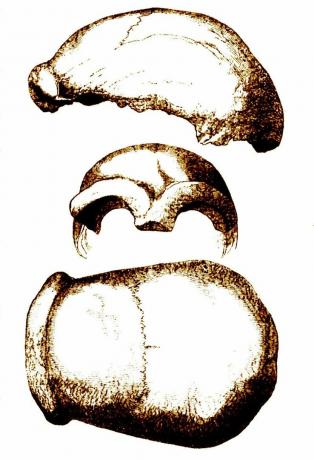

Fortunately, we have the hyoid bone, a tiny bone located at the level of the third and fourth vertebrae, which plays a large role in terms of the phonatory system. And it is that it is on the hyoid bone, the only bone of the vocal tract, where the tongue and larynx sit; As a bone, it goes without saying that the hyoid has the same capacity for fossilization as any other in the human body.

In 1989, the remains of a Neanderthal with an intact hyoid bone were discovered in Kebara (Israel), to which X-rays were applied. The results of the research, published in the journal Plus One, concluded that, indeed, the location and morphology of this bone in the Neanderthal species were practically identical to ours, so it was very possible that our relatives spoke the same as us.

- Related article: "The 6 stages of Prehistory"

The hearing abilities of the homo neanderthalensis

Now, a joint study by the Chair of Primitive Otoacoustics and Paleoanthropology of HM Hospitales and the University of Alcalá has reached similar conclusions through the analysis of the auditory abilities of neanderthals. Using computerized axial tomography techniques, It has been possible to reconstruct the cavities of the external and middle ear parts of some of the Neanderthal fossils from Sima de los Huesos, in Atapuerca; the result has shed light on the controversy of whether or not our relatives could speak.

The results of the study were published in the journal Nature Ecology & Evolution; in them it is affirmed that the Neanderthals could hear the same range of sounds that we do, which would also imply that they were probably capable of emitting varied sounds, since in general the hearing capacity is related to the communication. In other words: it is more than likely that Neanderthal men and women were capable of constructing an articulate language.

If it is true that Neanderthals were able to speak, we would have to accept that we are not the first and only species to do so. We already had to "give up" when it was shown that our relatives had abstract thinking, and that they even embellished themselves just like us and also felt affection and compassion. If the theory of Neanderthal speech is true, the similarities that unite us to our relatives would increase to unsuspected limits.

As María Martinón-Torres maintains in her interesting article on the oral capacity of Neanderthals, it is really difficult to believe that a species of such high intelligence (which, remember, he had a cranial capacity greater than ours), with an indisputable ability to decorate himself and create art, he did not have the ability to express himself in a language more or less complex. The path towards understanding Neanderthals remains open; let us hope that we continue to study them without prejudice and with an open mind to new surprises and possibilities.