Byzantine art: history, characteristics and meaning

Byzantine art is known as the set of artistic manifestations developed in the Eastern Roman Empire, called the Byzantine Empire, from the 4th to the 15th century. However, this style is still alive today as a vehicle of expression for the Orthodox Church.

Byzantine art was born with the rise of Christianity to the imperial court. At the beginning of the 4th century Maxentius and Constantine were fighting for the title of Augustus in the Roman Empire, then divided into two administrations: the Eastern and Western Roman Empire. Inspired by a dream that augured his triumph under the sign of the cross, Constantine defeated Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in 312.

Constantine assumed control of the Eastern Roman Empire, put an end to the persecution of Christians through the Edict of Milan (year 313) and adopted Christianity as his court religion. The seat of the Eastern Roman Empire was established in

Byzantium, where does the name of Byzantine Empire, even though Constantine did call the city Constantinople since 330.

The emperor and his successors felt the duty to provide conditions for the "cult", which was the germ of Byzantine art. But in the beginning, what the Empire had at hand was Greco-Roman art and architecture, designed for other functions.

On the one hand, pagan temples were conceived as the house of the god they commemorated, in such a way that no one could enter them. On the other hand, these temples housed a statue of the god in question, and the pagans believed that these were inherent to the god himself. Both principles were contrary to Christianity.

The first Christians inherited from the Jews the rejection of images, particularly sculptural ones. But in addition, they believed that God did not dwell in any temple and that worship was done "in spirit and truth." For this reason, they met in domus ecclesiae, Latin term that means 'house of the assembly' ("synagogue" in Greek), destined to share the word and to celebrate the memorial of the passion, death and resurrection of Jesus.

However, with the rise of Christianity, larger spaces were needed. Along with this, the Empire, still pagan-minded, aspired to clothe the Christian celebration with signs of status. Therefore, the researcher Ernst Gombrich proposes the question: How to solve this question in architecture and, later, how to decorate those spaces within the framework of a faith that prohibited idolatry?

Characteristics of Byzantine architecture

Thinking about all these questions, the Byzantines devised different ways to solve their artistic needs. Let's get to know some of them.

Adoption of the basilica plan and development of the centralized plan

The first solution that the Byzantines found was to adapt the roman basilicas or royal rooms to the needs of the liturgy and the imperial court. In this regard, the historian Ernst Gombrich says:

These constructions (the basilicas) were used as covered markets and public courts of justice, consisting mainly of large oblong rooms, with narrow and low compartments in the side walls, separated from the main one by rows of columns.

Over time, the basilica plant became a model of the Christian church, to which was soon added the centralized plant or Greek cross in the time of Justinian, an original contribution of Byzantine art.

Adoption of Roman construction elements

At the constructive level, the Byzantines adopted the constructive techniques and resources of the Roman Empire. Among the Roman elements they mainly used the barrel vaults, the domes and the buttresses. They also used the columns, although more with an ornamental character, except in the galleries where they function as a support for the arches.

New uses and architectural contributions

Byzantine architecture brought the use of pendentives as support for the domes, applied in the centralized plants. In addition, they diversified the capitals of the columns, giving rise to new decorative motifs. They preferred smooth shafts.

Development of the iconostasis

Special mention should be made of the iconostasis, a characteristic liturgical object of Eastern Christianity. The iconostasis, which comes from the templon, gets its name from the icons that "decorate" it. This device is a panel arranged on the altar of Orthodox churches from north to south.

The function of the iconostasis is to protect the sanctuary where the Eucharist (bread and wine) is located. In this sanctuary, normally located to the East, the Eucharistic consecration takes place, which is considered a leading sacred act of the liturgy.

In general, the iconostasis has three doors: the main one, called holy door, where only the priest can pass; the southern gate or diaconal and finally the northern gate. The set of icons that are arranged in the iconostasis usually represent the twelve festivals of the Byzantine calendar.

In this way, the iconostasis is a communication door between the celestial and the terrestrial and, at the same time, according to Royland Viloria reports, it condenses the Theological Summa of the East. To understand this, it is necessary to first understand the characteristics of Byzantine painting below.

Characteristics of Byzantine painting

Byzantine art was originally inspired by early Christian art. Like this, it reflected the interest in the Greco-Roman style of the Empire, of which he felt heir. At the same time, he assimilated the influence of oriental art. But the need to make a difference with paganism would cause a transformation that would necessarily go through thoughtful theological discussions.

Among the many circulating doctrines, the most accepted was the thesis of the double nature of Jesus, human and divine. Under the argument that “He is the Image of the invisible God”(Col 1, 15), the development of a Christian pictorial art was allowed. Let us know its rules, forms and meanings.

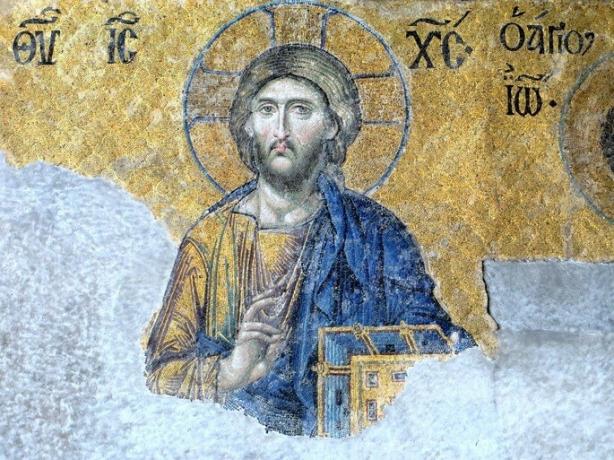

The icon as the highest expression of Byzantine art

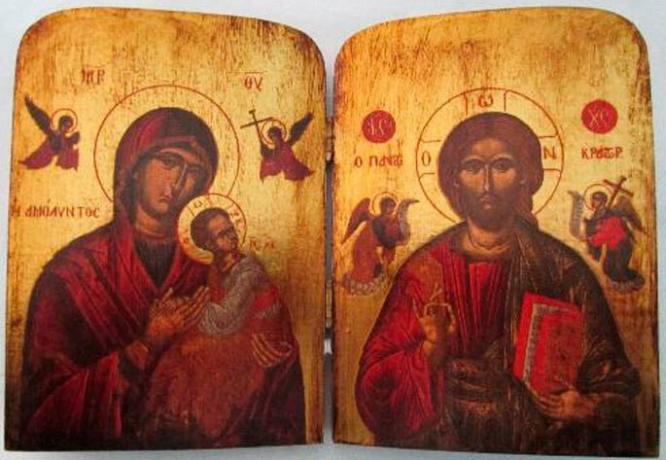

The main manifestation of Byzantine painting are icons. The word icon comes from the Greek eikon , which means "image", but they are conceived as vehicles of personal and liturgical prayer, as reported by Viloria. Therefore, sensuality is deliberately suppressed.

In ancient times, icons were made by iconographers, monks consecrated especially for the office of "writing" theology on icons (nowadays iconographers can be consecrated laypeople). The pieces were also consecrated. In its beginnings, the icons on the table registered the influence of the Fayum portraits in Egypt.

Unlike Western art, icons served liturgical functions. Therefore, they did not pretend to imitate nature, rather, they pretended to account for a spiritual relationship between the divine and earthly order, under strict theological and plastic standards.

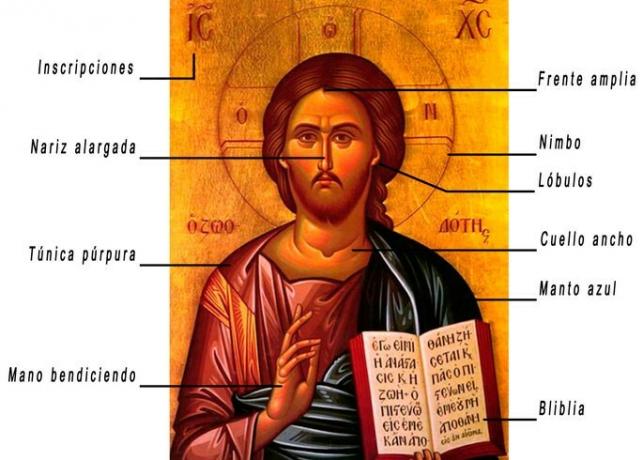

The face is the center of interest and reflects spiritual principles

The face is the icon's center of interest, since, according to researcher Royland Viloria, it shows the transfigured reality of those who participate in divine glory. That is, it condenses the character's signs of sanctity.

The construction is made from the nose, always elongated. There are two types of face:

- the frontal face, reserved for the holy characters by their own merit (Jesus) or who are already in divine glory; Y

- the face in profile, reserved for those who have not yet reached full holiness or do not have holiness in their own right (apostles, angels, etc.).

The ears they are hidden under the hair and only their lobes can be seen as a symbol of the one who listens in silence. The front it is represented wide, to account for contemplative thought. The neck (of the Pantocrator) appears swollen, indicating that it breathes the Holy Spirit. The mouth does not require protagonism; she is small and thin-lipped. The look it is always directed at the viewer, unless it is a scene.

The faces are usually accompanied by nimbus, symbol of the luminosity of bodies.

Using the inverted perspective

BELOW: Basic notions of perspective. Left: linear perspective. Center: axonometric perspective. Right: inverted perspective. Source: Royland Viloria (see references).

Byzantine art applies the model of inverted perspective. Unlike linear perspective, the vanishing point is located in the viewer and not in the work. Rather than seeing the icon, the viewer is seen by it, that is, by whoever is behind the material reality of the image.

Accentuation of verticality

Along with inverted perspective, Byzantine art favors verticality over depth. Thus the ascending character of theology prevails.

Colors embody theological concepts

In each icon, the presence of light is fundamental as a spiritual value, represented with the Golden or the yellow. The color gold, in particular, is associated with transfigured and uncreated light. This value remained unchanged throughout history. However, other colors changed or fixed their meaning after the triumph of orthodoxy in the 9th century.

The blue is usually symbolic of the gift of humanity, while the range of purple it usually represents the divine or royal presence.

For example, when Jesus is represented in a purple dress and blue cloak, he symbolizes the mystery of the hypostasis: Jesus is the son of God who has been clothed with the gift of humanity. Conversely, the Virgin Mary usually appears dressed in a blue dress and purple cloak as a sign that she is a human being who, by giving the Yes, has been clothed by divinity.

The green it can also symbolize humanity as well as life or the vital principle in general. The Earth colors they represent the order of the earthly. In the saints, the Red pure is a symbol of martyrdom.

The White, for its part, represents spiritual light and new life, which is why it is frequently reserved for the vestments of Jesus in scenes such as baptism, transfiguration and anastasis. By contrast, the black represents death and the dominion of darkness. The other colors they are arranged according to the gold inside the piece.

Mandatory registration

Icons always have inscriptions. These serve to verify the correspondence of the icon with its prototype. They are usually performed in the Byzantine liturgical languages, mainly in Greek and Church Slavonic, as well as Arabic, Romanian, etc. To this is added a theological argument, according to researcher Viloria:

This importance of the name comes from the Old Testament, where the “name” of God manifested to Moses (Ex 3,14) represents his presence and his saving relationship with his people.

Most used techniques

The techniques used in the Byzantine icons depend on the support. For the wooden supports the encaustic and the egg tempera. For the wall mounts, the technique of the mosaic (especially in the times of imperial splendor) and the cool.

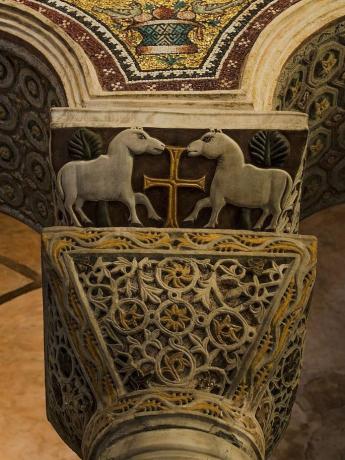

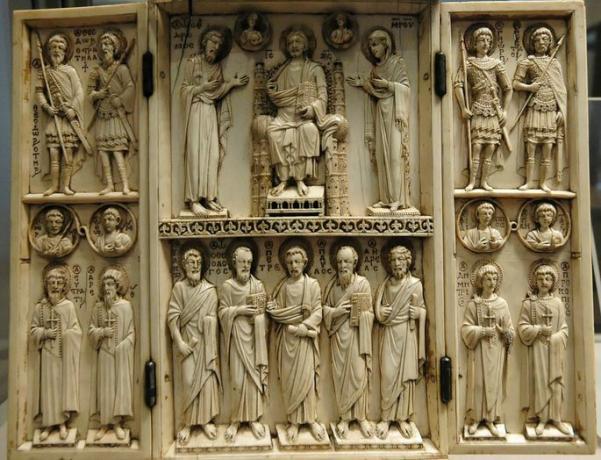

Characteristics of the sculpture

As a general feature, Byzantine sculpture established itself on the Greco-Roman tradition. It incorporated the iconographic elements of Christianity: not only the scenes, but the symbols and allegories: animals, plants, attributes, among others, were part of the new repertoire artistic.

Byzantine sculpture was at the service of architecture and applied arts, as was the case in the ancient medieval world. Round-shaped sculptures were not well regarded due to their resemblance to pagan idols, so the technique of the relief for sculpture for religious purposes.

Understanding the historical-theological context

The birth of the theological debate and the banishment of Arianism (4th-5th centuries)

When Christianity came to court, the recent imperial unity was threatened by disputes between Christian communities responding to different books and interpretations. At that time there were at least three major currents:

- the Arianism, defended by Arius, according to which the nature of Jesus was strictly human;

- the monophysitism, according to which the nature of Jesus was strictly divine;

- the thesis of the hypostatic union, who defended the double nature of Jesus, human and divine.

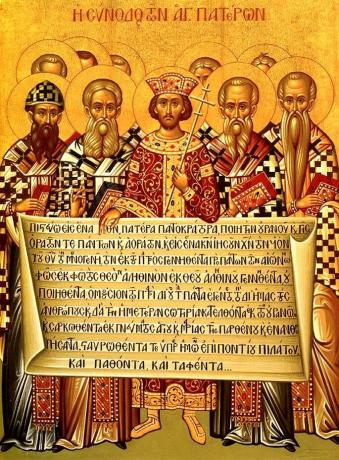

To end the conflicts, Constantine supported the convocation of the I Council of Nicea in 325. The council opted for the dual nature of Jesus, which resulted in the "Nicene creed." With this decision, Arianism was outlawed.

The Council of Nicea I, would be followed by others such as the I Council of Constantinople, held in 381. In this, the divinity of the Holy Spirit would be determined and the dogma of the Holy Trinity.

Such importance would have the Council of Ephesus 431, where the dogma of the Theotokos, that is, of the Mother of God, become a true iconographic type of christianity.

The exile of Monophysitism and the first splendor of Byzantine art (5th-8th centuries)

But even in the fifth century, the monophysitism he was still standing. The Monophysites were opposed to the images of Jesus as they considered him totally divine. Subjected to discussion in the Council of Chalcedon of 451, Monophysitism was outlawed, and the dogma of the double nature of Jesus was relegitimized, which would be spread through art.

It was only in the time of Justinian, in the 6th century, that Byzantine art was consolidated and reached its splendor. By then, although the political and religious powers were separate, in practice Justinian assumed powers in spiritual matters, giving rise to the cesaropapism. With a prosperous economy in his favor, Justinian fought Monophysitism through art, which had to be in the hands of artisans with a solid theological background.

Iconoclastic struggles and the triumph of orthodoxy (8th-9th centuries)

In the 8th century, the emperor Leo III the Isauric had a mosaic of the Pantocrator destroyed, withdrew the coins from circulation for this reason and banned religious images. Thus began the iconoclastic war or struggle, also called iconoclasm.

To end the war, Empress Irene summoned the II Council of Nicaea in the year 787. In this, the thesis of Nicephorus was accepted, who affirmed that if the son of God had become visible, what he himself agreed to reveal could be represented.

Along with the argument of images as a source of instruction for the illiterate, defended by Pope Gregory the Great in the century VI, religious images were once again allowed, but under strict regulations that sought to avoid all conduct idolatrous.

Byzantine art periods

Byzantine art spanned over eleven centuries, giving rise to stylistic differences that can be grouped into periods. These are:

- Proto-Byzantine period (4th to 8th centuries): It covers the entire gestation period until the consolidation of Byzantine aesthetics in the time of Justinian, which gave birth to the first Golden Age, which ended in 726.

- Iconoclastic period (8th to 9th centuries): it encompasses the entire cycle of iconoclastic struggles, in which a large part of the Byzantine artistic heritage was destroyed. It ended with the so-called Triumph of Orthodoxy

- Middle Byzantine period(867-1204): ranges from the triumph of Orthodoxy to the conquest of Constantinople by the Crusaders. Two dynasties were distinguished: the Macedonian (867-1056) and the Komnene (1057-1204). In the middle of that period, the Great Schism or Schism of East and West (1054).

- Paleological or late Byzantine period (1261-1453): It ranged from the restoration of Constantinople with the rise of the Palaeologos dynasty to the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Empire in 1453.

References

- Azara, Pedro (1992), The image of the invisible, Barcelona-Spain: Anagrama.

- Gombrich, Ernst (1989), History of art, Mexico: Diana.

- Plazaola, Juan (1996), History and meaning of Christian art, Madrid: Library of Christian Authors.

- Viloria, Royland (2007), Artistic, theological and liturgical approach to the icons of the Saint George Cathedral (Bachelor of Arts degree work), Caracas: Central University of Venezuela