Existentialism: definition and history of this school of thought

We have all wondered why we have come into the world and what is our role in it. They are basic and inherent questions to the human being to which, since always, philosophy and religion have tried to find answers.

Existentialism is a current of thought that seeks answers to human existence. Not only that; The existentialist current also tries to fill the distressing void that is produced when the human being questions the bases of his presence in the world. What am I here for? Why have I come? And, most importantly: does it make sense that I am?

Existentialism has developed over the centuries and, depending on the author and the historical moment, it has emphasized one aspect or another. However, and despite the obvious differences, all these ramifications have one point in common: considering the human being as free and absolutely responsible for his own destiny.

In this article we will review the bases of this current of thought and we will stop at the most important existentialist authors.

- Related article: "The 10 branches of Philosophy (and their main thinkers)"

What is existentialism?

Basically, and as its name indicates, Existentialism asks what is the meaning of existence or, rather, if it makes any sense. To reach certain conclusions, this school of thought performs an analysis of the human condition, dissecting aspects such as the freedom of the individual or his responsibility before his own existence (and that of others). others).

Existentialism is not a homogeneous school; its leading thinkers are scattered both in strictly philosophical realms and in literary circles. In addition, there are many conceptual differences between these existentialists, which we will analyze in the next section.

However, we do find an element that all these thinkers share: the search for a path of overcoming moral and ethical norms that, in theory, belong to all beings humans. Existentialists advocate individuality; that is to say, believe in the responsibility of the individual when making their decisionsTherefore, these must be subject to their own specific and individual needs, and not depend on a universal moral source, such as a religion or a specific philosophy.

- You may be interested in: "The 8 branches of the Humanities (and what each of them studies)"

existentialist individualism

If, as we have commented in the previous section, existentialists maintain that one must go beyond universal moral and ethical codes, since each individual must find his own wayWhy, then, do we find profoundly Christian thinkers framed in this current, as is the case of Kierkegaard?

Soren Kierkegaard (1813-1855) is considered the father of existentialist philosophy, despite the fact that he never used this term to refer to his thought. Kierkegaard was born into a family marked by the psychological instability of his father, affected by what, at the time, was called "melancholy", and which was nothing more than a depression chronicle.

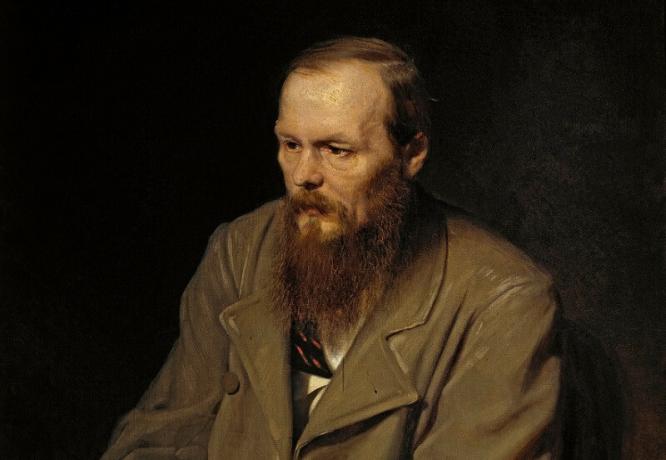

Young Soren's upbringing was eminently religious, and in fact he was a believer throughout his life, despite the fact that he was a forceful critic of the Lutheran ecclesiastical institution. Thus, Kierkegaard would be circumscribed in the so-called "Christian existentialism", in which we find authors as important as Dostoyevsky, Unamuno or Gabriel Marcel.

- Related article: "What is Cultural Psychology?"

christian existentialism

But how can you transcend universal ethical codes, as existentialism points out, through Christianity, which is nothing more than an ethical-moral code? Kierkegaard raises a personal relationship with God; that is, he places the emphasis, again, on individualism.

It is necessary, then, to forget about any pre-established morality and norm, valid in theory for all human beings, and replace them with a series of ethical and moral decisions that emerge exclusively from the individual and of his direct and personal relationship with divinity. All of this obviously entails absolute freedom, unlimited free will, which is what, according to Kierkegaard, causes anguish in human beings.

Christian existentialism has Kierkegaard as its standard bearer, but we also find important writers framed within this current, such as Dostoevsky or Miguel de Unamuno. The first is considered one of the first representatives of existentialist literature. Works like underground memories, The demons either Crime and Punishment They are authentic monuments to the suffering and transformation of the human being who, through free will, accesses a higher spirituality.

As for Miguel de Unamuno, his work stands out Of the tragic feeling of life in men and peoples, where the author is based on the theories of Soren Kierkegaard to delve into individualism and the internal anguish of the human being.

"Atheistic" Existentialism

There is another current within existentialism that differs significantly from authors such as Kierkegaard, Dostoyevsky, Unamuno or Gabriel Marcel. This other perspective has been called "atheistic existentialism", since it distances itself from any transcendental belief. One of the greatest representatives of this current is Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980).

In Sartre, free will and human freedom reach their maximum expression, by maintaining that man is nothing other than what he makes of himself. In other words, there is nothing definite when a human being comes into the world; it is his own decisions that establish his own meaning.

This, of course, completely contradicts the idea of the existence of a creator God, since, if the human being he arrives on earth without being defined, that is, without essence, it does not make any sense to suppose that he has been created by a being superior. Any creationist theory maintains that divinity creates the human being with a specific purpose. In Sartre, this is not so. Most existentialist thinkers agree on this: existence precedes essence, so it is only human will, his freedom and his free will, that can shape the meaning of being human.

Albert Camus (1913-1960) goes a step further by stating that, in reality, It is absolutely irrelevant to humans whether God exists or not.. Thus, questions about human existence do not depend on the answer to this question. This is why Camus has often been classified as an agnostic existentialist.

Albert Camus is the father of the philosophy of the absurd. Camus's absurdity takes existentialist philosophy to its limit, because when asked "Does life have meaning?" Camus answers with a resounding "no". Indeed, according to this thinker, existence does not make any sense; human life sinks into the most absolute absurdity. Therefore, it is sterile (and useless) to search for answers. What must be done, then, and according to the author in his famous work The myth of Sisyphus, is to stop asking questions and simply live. Sisyphus must be happy while he pushes the stone, since he has no way to get rid of it.

Responsibility causes anxiety

If, as we have affirmed, the human being possesses absolute free will (an idea in which all existentialist thinkers), this means that their actions are solely and exclusively the responsibility hers. And that is why the human being lives immersed in perpetual anguish.

In Kierkegaard's case, this anguish is the result of indecision.. Life is a continuous choice, a permanent encounter with one and the other. It is what the philosopher calls "dizziness or vertigo of freedom." The awareness of one's own responsibility and the fear that this entails is what leads human beings to deposit their choices in other people or in universal moral codes. According to Kierkegaard, this is the result of the terrible anguish of having to decide.

For his part, Jean-Paul Sartre affirms that the human being is responsible not only for himself, but for all humanity. In other words: the action you undertake individually will have consequences in the community. As we can see, the anguish in this case multiplies, since it is not only your life that is in your hands, but that of the entire society.

This vital anguish is what leads the human being to live a deep crisis and to project a disenchanted look at the world. Yes, indeed, all the moral responsibility falls on the individual; if, as existentialists (including Christian existentialists like Kierkegaard) maintain, we cannot embrace a universal code of values that guides us, then we find ourselves before an abyss, before nothingness absolute.

So how to get out of this discouraging situation? But before focusing on the "solutions" proposed by the various existentialist authors (and we put it in quotes because, in reality, there is no absolute solution), let us review the historical context that allowed the appearance of this current of thought. Because, although we can find traces of existentialism throughout history (for example, there are authors who point to Saint Augustine and Saint Thomas Aquinas as pre-existentialist authors) it is not until the 19th century that the current takes its full force. Let's see why.

- You may be interested in: "Existential anxiety: what is it and how does it affect the human mind?"

The context: the crisis of the 19th and 20th centuries

The Industrial Revolution, which began at the end of the 18th century, gradually turned man into a machine. There is also a strong religious crisis, in which scientific discoveries have a lot to do, such as Darwin's theory of evolution, among many others. The labor movements begin to take over the cities. The criticism of the bourgeoisie and the Church is increasingly pronounced and fierce. Progress intoxicates the human being, and he forgets God. The 19th century is, then, the positivist century par excellence.

At the same time, Europe is immersed in a progressive armament that will lead to the First World War. The European powers sign continuous alliances between them, which crack the continent. And, now that the 20th century has arrived, things will not improve at all: after the Great War, the rise of fascism takes place and, with it, the Second World War.

In this context of wars and death, the human being has lost the reference. He can no longer cling to God and the promise of an afterworld; religious consolation has lost its conviction. Consequently, men and women feel helpless in the midst of immense chaos.

In this context, the questions arise: Who are we? Why are we here? The existentialist current gains strength, and asks if the presence of the human being in the world makes any sense. And if you do, you wonder what your role (and responsibility) is in all of this.

the search for answers

In reality, existentialism is a search, not an answer. It is true that, as we have previously commented, various thinkers venture various paths, but none of them fully satisfies the existential conflict.

Soren Kierkegaard's Christian existentialism emphasizes a direct relationship with God, beyond pre-established moral and ethical codes. His philosophy is, therefore, radically contrary to that of Hegel, who forgets individuality as the engine of progress. For Kierkegaard, evolution can only occur from a constant vital choice, which emerges from the absolute freedom and free will of the human being.

For his part, Jean-Paul Sartre advocates an existentialism "without God", in which the human being makes himself through his own decisions. Man exists in the first place; later, he finds himself out in the world, alone and bewildered. Finally, and exclusively through his personal acts, he defines himself, without any divinity mediating in this definition.

Finally, Albert Camus proposes a solution that we could perhaps call intermediate. Through his theory of the absurdity of life, he affirms that the role of God in human life, as well as the meaning of the latter is completely irrelevant, and that the only thing that really matters is live.