Male Beauty Canons and their historical evolution

The beauty is relative. Surely you have heard this maxim many times; and it is, in fact, true. There is no such thing as an “official” beauty, and the concept of what is beautiful and what is not has been changing, depending on the culture and the historical moment.

It is often thought that the canons of beauty fall mainly on women and, however, this is not true. Men have historically been tied to different ideals as much as women and, in fact, still are; What happens is that, due to various variables, this tends to go more unnoticed.

How has the masculine ideal evolved throughout history? In this article we will try to briefly summarize the evolution of masculine beauty canons through different historical periods.

- Related article: "What is Cultural Psychology?"

Male beauty canons and their evolution in history

Practically since the human being exists, there has been a canon of beauty. The first human communities (and also our closest relatives, the Neanderthals) already exhibited certain aesthetic customs that reflected specific ideals of what was and what was not beautiful.

From ritual tattoos to body adornment with jewels made of shells, stones and bones; all of this is a clear manifestation that, beyond its possible ritual connotations, men and women have been keenly interested and from the beginning in feeling beautiful and attractive.

the beauty of the body

But the variables in the idea of the beautiful are not limited simply to external adornments. The first aspect to take into account is our original envelope, that is, the body. Indeed, the human body has been the object of multiple appreciations over the centuries, appreciations that have depended on the various cultures that have examined and valued it. Even today, when globalization hangs over the world without any kind of barrier, we find human communities that resist the “official” canon of beauty and continue to adhere to their tradition. This is the case, for example, of the Bodi, a tribe that lives in Ethiopia.

The masculine ideal of the Bodi is considerably far from what in the West we would call "beautiful". And it is that this culture has a curious ritual: for months, the men of the tribe are locked up and fed with a hypercaloric diet, consisting of cow's milk and blood, which makes them triple their body weight in a short space of time time. On the last day, a big party is held, in which men display their bulging abdomen due to excess fat. The one with the biggest stomach is the one who wins the hand of the most beautiful young woman in the tribe.

For the Bodi, masculine beauty goes through fatness, an idea closely connected to the concept of status: a bulging abdomen indicates a high-fat diet that ensures survival in a world where food is not always available enough. Even today, at a time when the Bodi have access to food, we see that this ancient idea has he survived to this day and has adhered to his culture as the prototype from which the beauty of a male.

- You may be interested in: "Canons of beauty: what are they and how do they influence society?"

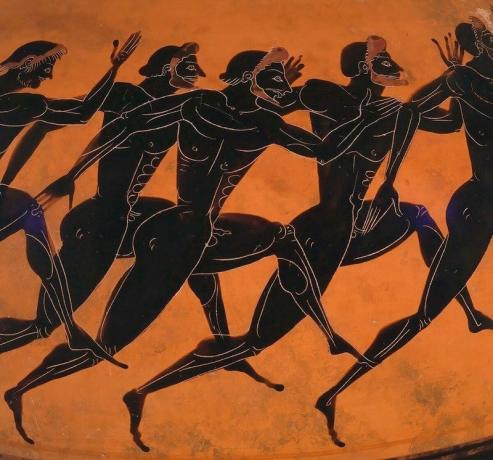

Muscular and athletic bodies

In the antipodes of the Bodi ideal of masculine beauty we have, of course, the classic ideal (which, in a certain way and without too many changes, survives to this day). In the ancient Greece, the canon of beauty for men was drawn mainly from the world of athletes and gymnasts; The ideal body, therefore, should be proportioned and properly toned, without being, yes, excessively muscled.

Grecia proposes a man who, although he is directly drawn from reality, presents in his idealized form a series of proportions that are not always found in nature. It can therefore be said that the Greek masculine beauty canon is a perfect balance between a body real (that of athletes, warriors and gymnasts) and a specific ideal canon, which varied over the years. centuries. Thus, for Políkleitos (480 a. c – 420 a. C) the ideal body should measure seven times the head. His most famous work, the doryphorus, is considered the marble representation of the masculine ideal of the time: we see a man, of a indefinite between youth and maturity, with an athletic and well-formed body and exquisitely muscled muscles. drawn.

With the Hermes of Praxiteles (4th century B.C. C.) we find an evolution of this ideal, since, although the god presents the same athletic body as his ancestor, we see that his silhouette folds into a counterpost which causes its volume to oscillate slightly. We are facing the typical "S" silhouette that was so common in Hellenistic times; an equally muscular man, but much more subtle and light.

- Related article: "The 5 ages of History (and their characteristics)"

The stylized medieval man

Obviously, we cannot summarize in so few lines the evolution of the ideal of masculine beauty. But we will talk about key moments, from which we will be able to extract a fairly complete vision of the whole.

Much has been said about the exacerbated medieval spirituality and the oblivion into which the subject of bodily beauty fell during these years. Could not be farther from the truth. You cannot conceive of an era or culture without a specific ideal of beauty, and the Middle Ages are no exception.

It can be affirmed, even at the risk of falling into reductionism, that in the Middle Ages beauty is color and light. The beautiful must necessarily be luminous, since beauty emanates from God, and God is light. Thus, the medieval centuries are stained with an extraordinary range of colors, each one more intense and brilliant. The brighter a hue is, the more beautiful the object it adorns will be considered. Thus, the mystic Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179), when she speaks of Lucifer before the fall (when he was the most beautiful angel) describes him adorned with gems, whose splendor can only be compared to the stars.

Thus, the masculine ideal of the time goes through a decidedly resplendent wardrobe. It is not unusual to see a knight dressed in a crimson doublet, a blue cloak, a green stocking, and a yellow stocking. In the same way, the jewels adorn the subject and surround him with beauty: rubies, emeralds and sapphires, all designed to cast an aura of light and majesty around the person concerned.

On the other hand, from the 13th century the canon of bodily beauty varies considerably. Fashion emphasizes parts of the body such as the waist (which should be very narrow) and the shoulders (which, on the contrary, should be the wider the better). So, the masculine ideal of the time resembles an inverted triangle, the shape of which is reinforced by the use of stiff shoulder cloth (in the manner of modern pauldrons) and extraordinarily short, narrow doublets. The resemblance of this masculine canon of the last centuries of the Middle Ages with that of the ancient Egypt, according to which men also had to have broad shoulders and very narrow waists. narrow.

This shortness in the garments that cover the torso is designed so that men exhibit two parts in which the sexual focus falls at that moment: on the one hand, the legs; on the other, the genitals. The ideal masculine not only has broad shoulders and a narrow waist, but also flaunts long, toned, and slim legs whose profile is accentuated by wearing tight-fitting stockings. As for the genitals, there was a real furor at the time for exaggeration, which would last for several more centuries; It is the time of the so-called "phallic case", a kind of hard cover that served to protect the male genitalia, since the doublets being so short, they were only covered by the socks.

In summary, at the end of the Middle Ages we find a muscular but graceful man, with a stylized silhouette reminiscent of Gothic cathedrals and with duly marked masculine attributes, a symbol of "masculinity" and "power". A curious balance between an almost ethereal ideal and the image of the fierce warrior who stands bravely (and often crudely) in battle and tournament.

Refinement and delicacy in the Renaissance

The Renaissance It is the time of the great princes. Although the Neoplatonism of the fifteenth century defends a type of almost symbolic beauty, beyond canons and proportions (a "beauty supersensible”, as Umberto Eco would say), in the 16th century the established masculine ideal was that of the powerful prince, with a strong body and robust, often thick, the best example of which can be found in the portraits of Henry VIII, considered one of the most beautiful of the time. The roundness of the shapes is a symbol of power, and slenderness comes to be seen more as a symptom of weakness or cowardice.

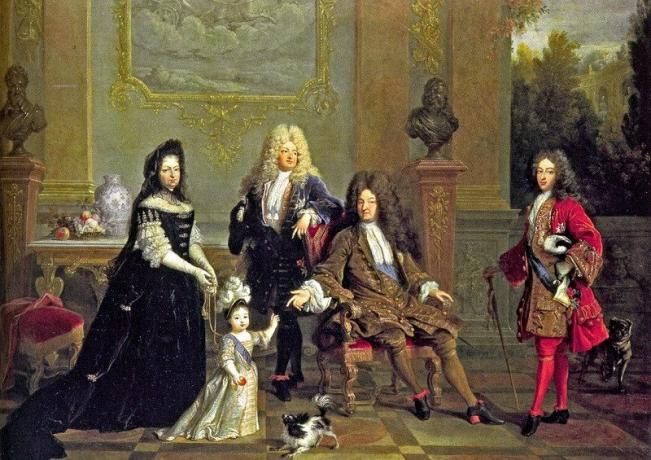

But since the canons are there to be broken, overcome and changed, from the second half of the 17th century we find the opposite. It is only necessary to take the portraits of Louis XIV and his court at Versailles to attest to this. The ideal of man has ceased to be "masculine", and beauty becomes exclusively related to grace and "femininity".

Thus, the "effeminate" man is empowered, even androgynous. Male beauty goes through the use of curly wigs, profusion of makeup and lipstick, as well as lace, bows and high-heeled shoes. We are facing the extinction of the warrior ideal and the appearance of a rather courtly, refined and exquisite ideal. The baroque man is a delicate, fine and courteous man, and any expression of extreme “masculinity”, which years before was a status symbol, is now seen as something vulgar and coarse.

Thus, this elegance and delicacy and the "savoir faire" are related to adornments that, much later, will be considered inappropriate for men.

disease is beautiful

The 18th century is the century of the Enlightenment and, as such, the prototype of a man is that of someone reserved, judicious and sober, of moderate customs and highly intellectual. The decorations of the baroque go out of fashion and, especially after the French Revolution and the advent of its ideal of "republican man", the austere and frugal became fashionable. It is the return of classical ideals: harmony, proportion, containment.

The arrival of the romantic movement once again shakes the aesthetic panorama. As Romanticism promotes the sublime, that is, that which escapes reason and is beyond the finite, a type of taciturn, dark and, above all, melancholic man becomes fashionable. Melancholy, (which, on the other hand, is nothing new in history), is the state par excellence of the romantic artist. So, the beautiful will inevitably be everything "sick", the decadent, the incomplete, what could have been and was not.

The man of Romanticism is an individualist and full of rebellion. It shows in his long and messy hair, in his slightly disheveled appearance and, above all, in the fire in his eyes. The ideal of masculine beauty of the romantic era is a man with a pale, emaciated face, which highlights the intense gaze of his eyes. We are again faced with the sick as a source of beauty: the greater the pallor and thinness, the greater the attractiveness. And, if the subject is "lucky" to have a fever, much better; the high body temperature will accentuate the strange glare of the look and will arrange some "beautiful" furrows under the eyes.

The beauty of the androgynous

Probably the opposite of this ideal is the famous dandy, of which Oscar Wilde is the best example.

At the end of the 19th century, the concept of "art for art's sake" is a true way of life for many men, who see existence as a work of art that must be lived to the fullest. The dandy, therefore, is a man who cultivates his image to the extreme, who wears strange but exquisite clothes, and who is wrapped in a refinement and opulence that make it contrast tremendously with the "official" masculine ideal, the gray and correct bourgeois.

The dandies of the late 19th and early 20th centuries are deliberately effeminate, and even androgynous. They take care of their body and its appearance with a precision that, at the time, they would call “feminine”. Something of this remained in the first decades of the 20th century, although in this case women were the protagonists, who left behind their traditional "femininity" to seek new ways of expressing the beauty. It is the time of androgynous beauty.

We cannot summarize here all the masculine ideals that followed one another in the 20th century, but we can ask ourselves: which ideal is the one that prevails today? A man close to doryphorus of Polykleitos, or rather a stylized and androgynous man?

The ideal of beauty is constantly changing. We are heirs of multiple cultural manifestations, so our prototypes combine a bit of all of them. The interesting thing is to verify that there is no absolute truth, and that what we can consider "beautiful" or "ugly" may not be so in other latitudes or in other social and historical contexts. Because what is more different than the men of the Bodi tribe and the athletes of ancient Greece? And yet, both are considered beautiful in their context, proving once again that beauty is relative.