Edvard Munch: 20 Brilliant Works to Understand the Father of Expressionism

Edvard Munch is a Norwegian painter located in the transition from the 19th to the 20th century, and is considered the father of Expressionism. His work, scandalous for many, aroused the admiration of young artists and the non-specialized public. These were identified with the anxiety generated by the rapid industrialization and the prevailing mechanism.

For established artists, the cause of scandal was in Munch's technical freedom. For the conservative sectors, it was based on the fact that the painter openly addressed subjects such as sex, love, and, above all, illness and death, his great obsessions.

His style was unique thanks to the fact that it created an authentic and original language, a consequence of freely dialoguing with post-impressionism, art nouveau and avant-garde. That is why, although Munch opened the doors of expressionism, he cannot be labeled in any movement. By taking a look at his most important works, we will understand why Munch is a unique and unrepeatable artist.

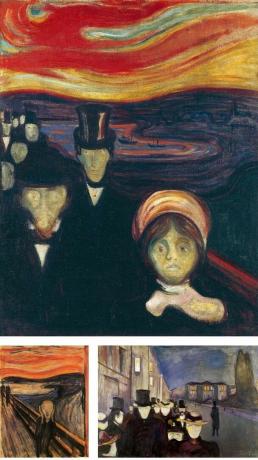

1. The Scream, 1893

Below - different versions of The Scream, by Edvard Munch

The Scream It is Munch's work that unleashed the most scandal and, nevertheless, today it is considered the Mona Lisa of contemporary art. It represents an androgynous person whose face expresses anguish in its maximum expression after hearing or uttering a scream. The subject, consequently, perceives the world as an undulating and strident mass. No one but Munch had done this before in art.

The play was conceived after the period in which one of his sisters was imprisoned for attempted suicide, which suggests some connection to the episode. A curious fact about The Scream is that Munch made four versions with slight differences between them, a very common practice in the painter. The most famous version is that of 1893, which was stolen in 1994, and recovered shortly after.

2. Anxiety, 1894

Under - The Scream (left) and Afternoon on Karl Johan Street (right), by Edvard Munch.

Yes The Scream It is the image of individual despair Anxiety it is the expression of the collective anguish that Munch captures in the Norwegian soul. Therefore, Munch is not an artist limited to the register of individual discomfort, but he is sensitive to general discomfort. affecting society at the end of the 19th century, whose transformation is much faster than its ability to process changes.

The canvas Anxiety It is based on two previous Munch paintings. The landscape we see in Anxiety has been recovered from the canvas The Scream. The characters, on the other hand, have been taken from Afternoon on Karl Johan Street. The strategy of taking elements from previous frames is recurrent in Munch. The painter not only "represents" scenes, but the elements that constitute them are conceived as his own symbols.

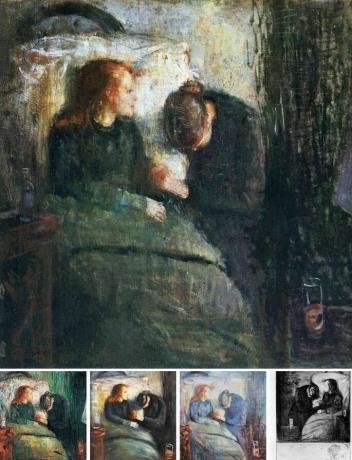

3. The sick girl, 1885-1886

Below - different versions of The sick girl.

The sick girl corresponds to an early style in Munch's work, which is close to impressionism. The canvas depicts Munch's younger sister, Sophie, on her deathbed from tuberculosis. By then, the young woman was about 15 years old.

As was his custom, Munch performed different versions of this theme, which was a permanent source of pain and guilt for him. This was due to the fact that the painter, who had suffered from tuberculosis at the age of 13, felt that he must have died instead of his sister.

4. Love and Pain (Vampire), 1893

Munch titled this work Love and pain. In it, he represented a woman embracing a man who lies on her lap, as if seeking comfort. Although Munch never revealed the personal meaning of the work, the original title speaks volumes. However, when this piece was revealed, it sparked a huge scandal.

People saw sadomasochistic signs in her, and interpreted that the woman was biting the neck of her lover as a vampire. Consequently, the painting began to be known as Vampire. Such was the scandal that, years later, this was one of many Munch paintings censored during the Nazi occupation of Norway.

5. Madonna, 1894

The box known as Madonna it was originally titled Lover woman or Woman who loves. Rename the work Madonna it is undoubtedly a provocation. Munch produced at least five known versions of this piece.

The artist makes a representation of the woman as if she were an icon, to imply the sense of adoration that her beauty and sexuality awakens. The red halo that surrounds his head alludes to the relationship between love and pain, even during the consummation of the sexual act.

This hypothesis is justified because Munch made an engraved version, the frame of which included decorative motifs of sperm that converge on a macabre fetus. In conclusion, the painting is a symbol of the cycle of life that passes through sexuality, procreation and death.

6. Ashes, 1894

Ashes It is considered one of the works with the greatest aesthetic beauty of Munch due to the threading of the lines and the coloring. In the composition, we see a man in black, the color of darkness and death. The man is lost in a corner, as if hiding his face in shame, with his hands to his head. It reminds us of the dejected man of Love and pain (Vampire).

Behind him, a woman in a white dress, the color of purity, and with a red bodice, the color of passion, also raises her hands from him. His face expresses sadness and concern. The veil of passion has been torn.

The relationship between the image and the title points to a paradox: when passion is consumed, it dissipates. The fire of passion leaves only ashes. But in addition, the gestures of the characters evoke guilt and despair. This reveals that the event defies a moral code. Is it adultery? Was it a rape? It must be the viewer who deciphers it.

7. Puberty, 1894-1895

On Puberty, Munch depicts a completely naked young teenager. The young woman has a fearful face and hides her private parts. More than a symbol of modesty and innocence, gestures are a symbol of fear and repression in the face of sexuality, which Munch suffered in his youth, given the religious rigor of his father and the context of the epoch.

The mysterious mood of the scene is confirmed by the indecipherable shadow in the background, which looks like a kind of haunting phantasmagoria. The importance of this early work by Munch lies in the fact that it represents the point of change between the "impressionist" stroke and the liberation of technique at the service of the artist's psychological world.

8. Self portrait with cigarette, 1895

Self portrait with cigarette It is one of Munch's most famous works, as well as being the best-known self-portrait of him among the many that he made. On the canvas, the author demonstrates an understanding and absolute mastery of the technique to represent the glow of light amid darkness and smoke.

In doing so, Munch builds an almost mysterious atmosphere that draws attention to her face and his hand. Her face looks between puzzled and surprised, while her hand, in addition to holding the cigarette, rises to the level of the heart. If the face is the sign of the inner identity of the subject, affected by emotional instability, the hand is the symbol of the plastic artist.

9. Death in the room, 1895

During his childhood, Edvard Munch saw many family members die of tuberculosis: his mother and his father are some of the cases. Death in the room he represents the suffering of his family at the loss of his younger sister, Sophie, whom we do not see. It is a genius of the author to focus the viewer's attention on emotional suffering rather than death.

The man who raises his hands in a prayerful attitude is his father, a severe Protestant religious. The man leaning against the wall is believed to be Munch, who turns his back on the scene (death, affection, and faith), while looking straight at his own shadow. It highlights the fact that each member of the family suffers separately.

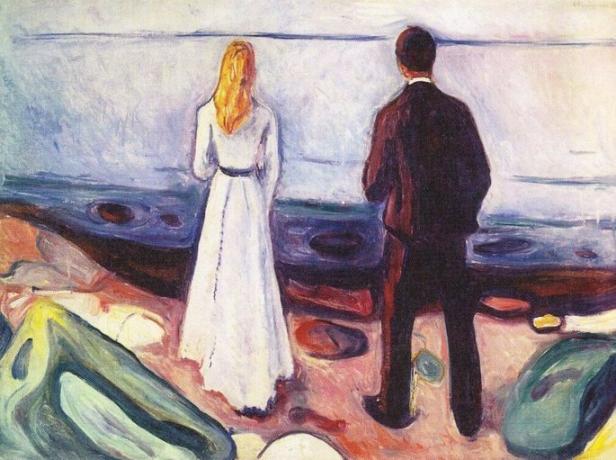

10. Two human beings (The lonely ones), 1896

The canvas Two human beings it is nothing more than an allegory of loneliness. In it we see a man and a woman without identity, with their backs to the viewer, contemplating the inert horizon. Between the two there seems to be an insurmountable distance.

The work, like many others by Munch, was covered numerous times and in different techniques. Both the theme and the way of representing it confirm the anxious, lonely and depressive character of the artist.

11. The kiss, 1897

The kiss, from 1897, is one of the versions of the painting known as The kiss behind the windowby Munch himself. The way in which the painter represented the two figures stands out. They look like a single body, with no dividing lines between them. The characters lack identity, their own limits.

The fusion of the characters cannot be read romantically, since the dark and heavy atmosphere of the scene also suggests the proximity of death. The impact generated by this series was such that it inspired the famous work The kissby Gustav Klimt.

It may interest you: Analysis of The kissby Gustav Klimt.

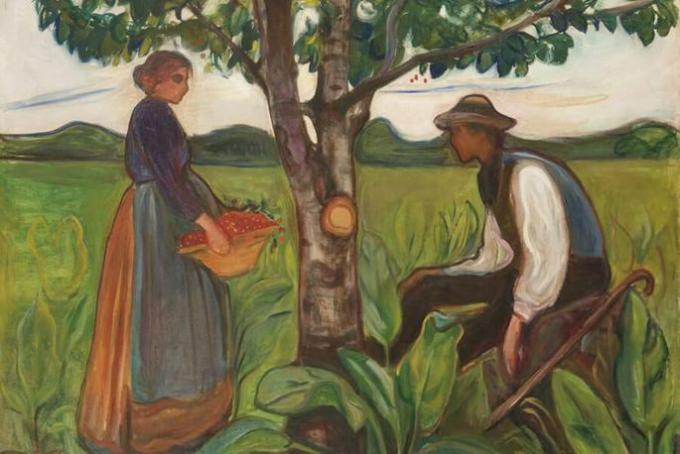

12. Fertility, 1898

On the canvas Fertility from Munch we see a pregnant woman, erect, carrying the abundant fruits of the tree. In front of her, the man sitting, crestfallen and stooped, contrasts. A fallen cane can be seen beside her. There is a continuity between the man and the tree because the former supports his foot on the trunk of the tree.

The tree could be interpreted as the tree of life. However, she has cut off a branch, of which only a stump remains. In order to bear fruit, the tree has been pruned, dismembered.

More radical interpretations suggest that Munch expresses his rejection of having children. Her fruits would represent the end of his fruits. The interpretation is based on the fact that the painting was painted when Munch was faced with the possibility of getting married to Tulla Larsen, a commitment that was never consummated.

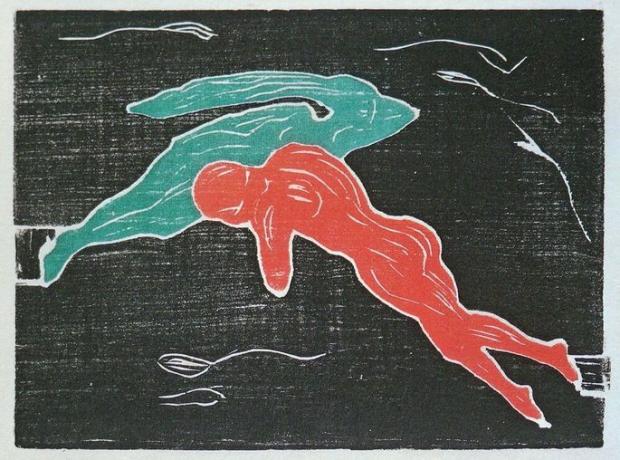

13. Meeting in space, 1898

On Meeting in space we see a man and a woman gravitating in space. The work represents an erotic moment, demarcated not only by bodies and gestures, but also by lines allusive to sperm move around the figures. His faces are distant from each other. The woman seems almost indifferent. The man seems delivered. The piece shows the technical versatility of the author, as well as the symbols and expressive resources.

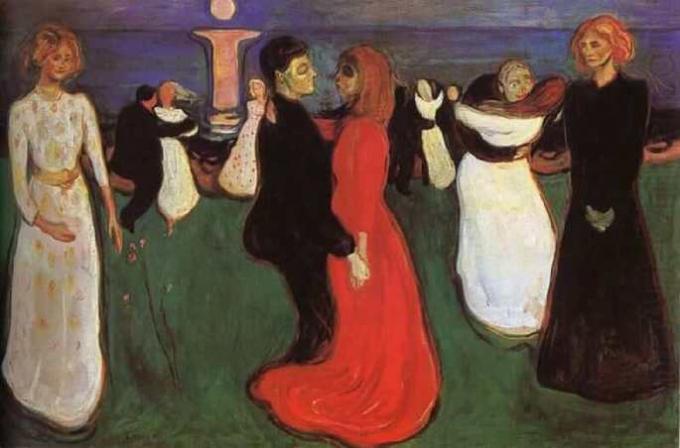

14. Dance of life, 1899

Dance of life it is a metaphor for the stages of life and love. It is an outdoor scene, the background of which is a deep blue sky over a Norwegian lake. In the sky, we see the northern sun and its reflection in the water, one of the symbols that is consistently repeated in the painter's paintings.

In the foreground, we see the same woman in three stages: a young maiden in white on the left. On the right, a lonely woman dressed in black. In the center, the woman and hers, her man, dancing as if the world did not exist. The red of her dress symbolizes life and passion. The couple could be Tulla Larsen and Munch.

Around them, other characters dance. Behind the woman in black, a grotesque man is seen ready to abuse a woman. The importance of this work lies in the way in which Munch manages to convey the complexity of his inner anguish around the stages of life, which he circumscribes to love.

15. The death of Marat, 1907

During a period of his life, Munch devoted himself to making various versions of The death of Marat. Among these versions, we present one made in 1907. Marat was an 18th century French journalist and politician, who was assassinated by Charlotte Corday.

The series seems to have Munch himself as a male reference, thereby consolidating the idea that the painter felt himself a victim of women. From an aesthetic point of view, the work stands out for the use of lines as a form of coloring. It is a kind of rayonism that breaks with the modernist style of the curved line and with the use of dense colored surfaces.

16. Bathers men, 1907

Bathers men de Munch stands out for his lively and vibrant character, which is opposed to the undulating and dark atmospheres of many of his canvases. The scene depicts a group of men on a nude beach, where Munch was spending a period of recovery.

Munch shows off his knack for anatomical drawing, as well as his knack for coloring. The implemented technique is nourished by impressionist and rayonist principles and, in some aspects, seems to dialogue with Fauvism.

17. Sun, 1909-1911

Sun is a monumental mural by Edvard Munch found in the University of Oslo. In this, Munch explores new plastic languages that bring him closer to abstract avant-garde, especially Kandinsky, representative of the group Der Blaue Reiter, and lyrical abstraction.

The symbolism here reaches its maximum expression. The sun becomes a metaphor for the divine, which radiates its light on the world and clears the shadows of ignorance. With this work, Munch demonstrates once again his creative freedom, which explains why he cannot be labeled in a single style or movement. Munch reveals himself as a unique artist in constant innovation.

You may also be interested in: Expressionism: characteristics, works and authors.

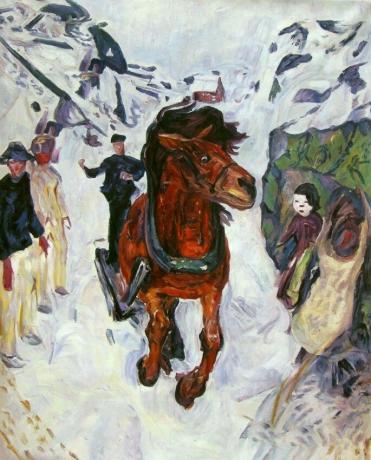

18. Galloping horse, 1912

In the frame Galloping horse, we see a horse pulling a snow sled with a man on board. The eye-catching detail is on the trail, which stands out as being excessively narrow for the feat.

The frightened expression of the horse and the disposition of the people on the side of the road give us to understand an imminent danger. The children on the right try to get away, while the adults on the left wait undaunted before moving. It is a new approach to the subject of fear and anxiety, so present in the author.

19. Workers in the snow, 1913

Edvard Munch was also sensitive to the social reality that surrounded him. Proof of this are the different paintings that he made on the workers, such as this canvas called Workers in the snow.

In the foreground, Munch represents three workers standing in front of the viewer, with their shovels as a fulcrum. In them you can sense strength, but also fatigue and aging.

The raised fist of the worker arranged in the center, makes a premonition of a claim or demand. These three men seem to be up in arms. Behind these three characters, the other workers continue their work, oblivious to the gaze of the artist and society.

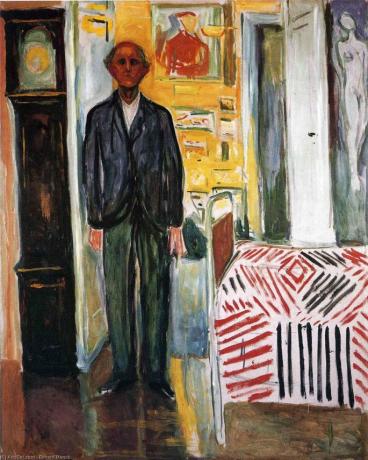

20. Self-portrait between the clock and the bed, 1940-1943

Self-portrait between the clock and the bed it is a painting from Munch's last creative stage. Munch took advantage of the canvas to symbolize the proximity of death, placing his figure between a grandfather clock and the bed. The clock represents the unstoppable passage of time, and the bed represents death as the final bed, as eternal rest.

One detail stands out by contrast: while the clock has an antique design, the bed cover has a modern geometric design. With this, Munch expresses the conscience about the dramatic change of the times that he had to live.

Behind Munch a kind of room can be distinguished in which the presence of referential works of his artistic life is implied, to which he has devoted all his efforts.

See also: Frame analysis The Scream by Edvard Munch.

Biography

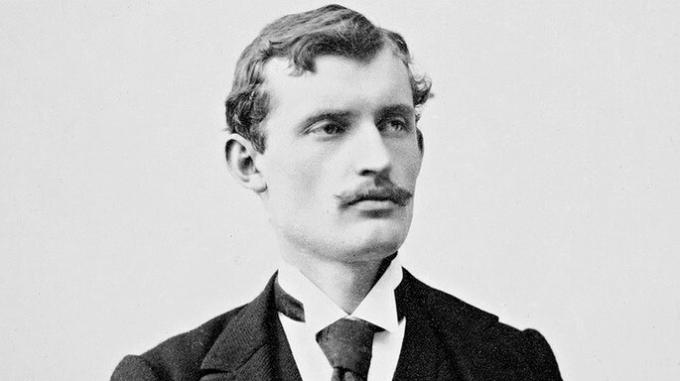

Edvard Munch is a Norwegian painter and printmaker who was born on December 12, 1863, and died on January 23, 1944.

From a very young age he had to deal with illness and death. Tuberculosis first claimed the life of his mother, Laura Cathrine Munch, when the boy was just 5 years old. Later, he caused the death of his younger sister, Sophie; that of his uncles and, years later, that of his father, Christian Munch. Even Edvard Munch himself suffered from the disease at age 13.

These events led the painter to develop a terrible terror of illness and disease. death and, therefore, he suffered from anxiety and depression all his life, which determined his inquiries artistic.

Munch began studying engineering in 1879, but he soon abandoned this career to dedicate himself to painting. He was influenced by 19th century French art thanks to his trips to Paris. Around 1890 he began to paint the project The frieze of life, a series of paintings depicting different milestones in human life, based on his own experiences.

Although his work was a source of scandal at first, it ended up gaining an important place in the museums of his country and Europe. However, after the Nazi occupation of Norway, around 1940, Munch's paintings were censored by the invaders and were removed from exhibits.

However, the year 1942 meant his definitive international consecration as he was the subject of an exhibition in New York in recognition of his fruitful artistic work. Two years later, Munch died in utter loneliness.