The passion of Christ in sacred art: symbols of a shared faith

In the history of Western art, the passion of Christ is one of the most developed themes, so his iconography is familiar to us. However, do we miss some hidden meanings of the passion of Christ in art?

Passion is a word that comes from Latin passio, derived in turn from pati, which means 'suffer', 'suffer', 'tolerate'. For this reason, the last hours of the agony of Jesus of Nazareth are known as "the passion of Christ."

The Passion of Christ encompasses various episodes in the Gospels, all of them loaded with rich symbolism. It condenses, on the one hand, the fulfillment of the Old Testament prophecies, according to which the envoy of God would be rejected and killed. On the other hand, the coherence of Jesus, who in the darkest hour lived as he had preached.

Let's get to know some works that cover the passion of Christ in the history of sacred art.

Prayer in the garden of olive trees

After having celebrated Passover with the apostles and aware that Judas would betray him, Jesus retired to pray in the so-called garden of olive trees. With no escape, he prepares spiritually to face the dark hour. Pedro, Santiago and Juan accompany him, but they fall asleep. Sweating the blood of anguish, he pleads with God to free him from martyrdom: "Father, if you want, take this chalice away from me, but may not my will but yours be done."

The chalice with the wine is the symbol of the blood that he has to shed. Like wine, it will be the cause of life and benefit. The representation of the scene usually includes the angel who, according to the Gospel of Saint Luke, appeared before Jesus to strengthen him.

In the work Prayer in the Garden of olives From 1607, El Greco collects the essential elements of the passage from a mannerist aesthetic. The lower half of the painting represents the apostles Peter, James and John in foreshortening and at a closer distance from the viewer. In the upper half, Jesus prays in front of the angel who presents him with the chalice.

Following the Byzantine model, Jesus wears a purple dress, a symbol of his divine condition, and a blue cloak, a symbol of his human incarnation. In the background to the right, you can see the procession that comes to arrest him. As is typical of El Greco, the figures are more stylized at the upper end, to accentuate their height.

With more than two centuries of difference, Francisco de Goya bets on a representation of Prayer in the garden of olive trees that reveals much more the anguish of Jesus. Unlike El Greco, Goya colors his clothing white in allusion to the purity of his soul. The gesture of her open hands and her gaze reveals concern about the fate that lies ahead. Goya's Jesus is an anguished Jesus, and Goya's technique anticipates the pathos of expressionism. The line used by the painter reveals that his style was close to the time of the calls Black Paintings.

See also: The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci.

The arrest of Jesus

The arrest of Jesus took place in the darkest hour of that night in Gethsemane when, knowing the illegality of his action, the authorities wanted to take Jesus by surprise. It took Judas's treacherous kiss so that they could identify the Master, since according to apocryphal sources, Jesus and James were very similar and, unlike the Pharisees, the authorities in Jerusalem knew little or nothing.

Peter, convinced that the restoration of Israel has come, draws his sword and cuts off the ear of Malchus, the servant of a high priest. Jesus rebukes him, heals Malco and surrenders himself to the authorities so that no one dies for his cause: "It is me they are looking for," he says.

From an iconographic point of view, there will be painters who stop only at one of these moments. Others, on the other hand, will choose to represent both moments simultaneously.

Duccio di Buoninsegna, a painter of the School of Siena in the context of international Gothic, represents each of the elements of the scene in his version of The taking of Christ. On the left, Pedro can be seen cutting off Malco's ear. In the center, Jesus receives the treacherous kiss from Judas, while the disproportionate procession surrounds him as if he were a dangerous criminal. On the right, the apostles flee and leave him.

In his version, the baroque Caravaggio draws attention to the kiss of Judas. Jesus keeps his hands clasped in a prayerful and peaceful attitude, while the soldiers go on top of him. The disproportionate use of force is evidenced, of a guard that not only outnumbers the victim, but also wears useless armor. Behind Jesus, one of the apostles screams and tries to flee while his cloak falls, as the scriptures relate. Some exegetes hold that this is John.

You may also like: Baroque: characteristics, representatives and works.

The trial

Jesus appeared first before the high priests who, having no authority to kill him, took him before the Roman attorney Pontius Pilate. Although he found no fault in him, in keeping with the tradition of releasing a prisoner for Easter, he made those present to choose between Jesus and the rogue Barabbas. This is how he "washed his hands" of all responsibility.

Right: Albrecht Dürer: Pontius Pilate washes his hands. 1512. Stamp. 117 x 75 mm.

The representation of this moment is not so frequent in western art. More frequent are, instead, scenes parallel to the judgment, such as Peter's denial and repentance. Still, some artists have represented this theme at different times.

In the mannerist work Jesus Christ before Pilate, Tintoretto represents the moment when Jesus comes back from the home of Herod Antipas, who has dressed him in white as a mockery. According to the sources, Tintoretto would have been based on a print by Dürer.

Flagellation

Pilate gave the order to scourge Jesus, although it is not clear whether the order came before or after the death sentence. According to the Gospel of John, the punishment of the scourging would have been an attempt by Pilate to dissuade the Sanhedrin from killing Jesus. Other evangelists maintain that the order of the flagellation was the beginning of the martyrdom of Jesus that had already been decided.

In any case, in the artistic representation of this scene, the artists usually focus on the ugliness of the soldiers, who enjoy the violence they inflict on the innocent. The scene is, then, the representation of beauty as an image of goodness, compared to ugliness as an image of evil.

Ecce homo and the crowning with thorns

According to the Gospel of John, Jesus received the crown of thorns and the purple robe at the time of the scourging, after which Pilate decides to expose him to the crowd with the words: "Ecce homo", which means' Here you have the man'. According to Matthew and Mark, it was after the exposition and condemnation of Jesus that the soldiers crowned him, dressed him in purple, and uttered the expletives.

In any case, the attributes of Jesus in the paintings of the type Ecce homo Y The crowning with thorns (crown of thorns and purple cloak) are usually the same, depending on the intention of the artist or the evangelical story on which it is based (for example, in the Ecce homo the purple color of the robe may vary by white). However, at the Crowning with Thorns Jesus appears alone with the soldiers, while at the Ecce homo, usually appears with Pilate alone or with other additional characters, including the crowd.

In The Crowning With Thorns or The expletives of Bosco, not only includes the soldiers, but also the Jewish authorities, represented by a man to the left of the painting. This man carries a cane with a crystal ball in which the face of Moses can be seen.

The Renaissance Titian, for his part, offers us this version of the Ecce homo in large format, where the tension of the scene and the violence inflicted on the person of Jesus are evident.

With the passage of time, the representation of the complete scene of the Ecce homo was giving rise to the unique representation of Jesus on a neutral background, which seeks the timeless piety of the viewer. Thus, some artists will give the scene of Ecce homo a narrative character, while others will seek to develop with it a pietistic sense. It will be the case of Ecce homo de Murillo from 1660, located in the middle of the Baroque period.

The road to Calvary or Way of the Cross

The road to Calvary, also known as Way of the Cross, is a sequence of 14 scenes that summarizes the itinerary of Jesus from the exit of the Praetorium to the burial. This itinerary is nourished by evangelical and apocryphal sources. When not working as a series, the plastic representation of the "Camino de Calvario" usually goes to scenes such as the imposition of the cross, the passage of Simon of Cyrene, the passage of Veronica, the passage of the daughters of Jerusalem and the plunder.

The authorship of the work Christ carrying the cross It is not entirely clear, because El Bosco did not usually sign his works or date them. It could have been made by him or by a copycat, as it appears to be quite late.

In this table, the humanity of Jesus contrasts with the animalistic and monstrous character of his victimizers, men who have allowed themselves to be debased by evil. Towards the lower left corner, you can see Veronica wearing the veil where the face of Jesus has been marked. She is also an image of the gift of humanity.

The crucifixion

The crucifixion is the high point of the passion of Christ. There, the symbolism runs through each element, and each detail generates an interpretive variation in the art. Jesus is usually represented on the cross accompanied by Mary, her mother, Mary of Magdala, and John. However, we will also find representations of Jesus crucified in absolute solitude.

The sign that tells us if Jesus has already died on the cross is the wound in his side. If this wound did not exist in the representation, the work would be referring to the last hours of agony in which Jesus uttered the so-called "seven words."

On The crucifixion by El Greco, we can see Jesus accompanied by the Virgin Mary, Mary of Magdala and John the Evangelist. Next to the cross, three angels are in charge of collecting the blood that flows from his wounds. In the scene, the context disappears and the cross rises above the gloom of the atmosphere, a symbol of the darkest hour, the definitive hour of Jesus' death.

Diego Velázquez, for his part, offers one of the most influential images of the crucifixion. In it, he removes the elements of the scene's own pathos, to privilege the representation of Jesus as the most beautiful man among men, following Psalm 44 (45). It is, without a doubt, an Apollonian model that contrasts with the searches of the Baroque period to which it belongs.

Velázquez prefers that Christ, whom we know dead from the wound in his side, appear to be in a deep sleep. Unlike other representations, the Crucified christ de Velázquez is supported by four nails at the suggestion of Francisco Pacheco, a painter and writer who defended the historicity of this iconographic model.

The descent from the cross

Jesus was crucified on a Friday. Since the Jews could not do anything on the Sabbath, they asked the Romans to lower the body of Jesus before the day fell. The same was to be done with the two criminals crucified on either side. To hasten the death of the evildoers, they broke their bones, but since Jesus had already died, A soldier named Longinus, pierced Jesus' side with a spear, and from his wound came blood and Water.

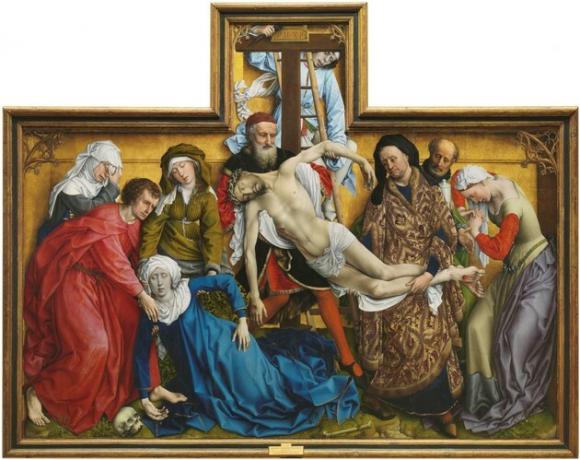

Rogier van der Weyden, representative of the Flemish Renaissance, includes two episodes in a single scene: the descent from the cross and the spasm of the Virgin Mary which, according to the apocryphal text known as the Acts of Pilate, would have happened when Mary recognized Jesus in the caravan of the Way of the Cross and not properly before the cross.

Over time, it was preferred to represent the Mother standing next to the cross (Stabat Mater), in attention to the Gospel of John. This attitude was considered to be more consistent with the image of Mary as a woman of faith.

Thus, we see in the Descent from the cross by Rubens, a affected but upright Mary, who participates in a resolute way in the process of lowering the body of Jesus. The mother contrasts with Mary Magdalene and Mary of Cleopas who lie lamenting at the foot of the cross.

The piety Y Lamentation over the dead Christ

The descent from the cross is usually related to other passages: piety and lamentation over the dead Christ, which precede the Holy Burial in that order. None of these passages are recorded in the gospels.

According to Juan Carmona Muela, the iconography of the piety, that is, of the Virgin Mary holding and contemplating the body of her dead son, became frequent in popular devotion at the end of the late Middle Ages. The iconography of lamentation also emerged, where Jesus lies horizontally while all his mourners cry to him.

La Piedad, in particular, is part of a spirituality open to the humanization of religious content, where the idea of the Virgin Mary as the throne where Christ establishes his power, gives way to the mother who shares suffering with humanity. It was natural to imagine a Virgin Mary saddened by that tragic episode, not only because of the tragic result, but especially because of the evil revealed.

The most difficult thing to solve in the iconography of the Pietà, according to Carmona Muela, was to fit the figure of an adult Christ on the mother's lap. At first, some artists had several characters accompany the scene, among whom Jesus was supported. Others chose to distort the proportions and make Mary larger than Jesus, something that Michelangelo himself does in his famous piety sculptural. This last resort led to the classic pyramidal representation that allowed the proportions to be balanced.

See also the meaning of the Sculpture The piety by Michelangelo.

The grave or the Holy Burial

As the Gospels describe it, Jesus was cloaked and perfumed in accordance with tradition. The biblical sources, however, do not agree on the characters that were present. Starting at Acts of Pilate, an iconography was set that includes:

- the Virgin Mary, mother of Jesus;

- Mary Magdalene, the woman whom Jesus had dignified;

- Joseph of Arimathea, who was a member of the Sanhedrin and secretly followed Jesus;

- Nicodemus, a Pharisee and magistrate;

- María Salomé, mother of Santiago el Mayor and Juan;

- John the Evangelist, who testifies to his presence on the scene.

They highlight the presence of Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, who until then had hidden the following of Christ for fear of the authorities. The reaction of both is, then, excessive: if on the one hand Joseph of Arimathea dares to ask Pilate's permission To bury the corpse, Nicodemus overflows by carrying thirty pounds of myrrh perfumed with aloe.

Final words

These overflowing gestures of Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea, in our opinion, highlight the role of symbolism of bread and wine as the body and blood of Jesus within the narrative sequence of the gospels, at least up to a certain point.

If in life Jesus was "bread" that fed the spiritual restlessness of the believers, that he has not yet fully understood what Jesus taught, his blood shed from him was the occasion of the awakening of conscience and Of value. The experience encouraged them to "correspond."

From the perspective of the evangelical accounts, in the face of the force of evil that seems to dominate everything, good overcomes, becomes courageous and builds community. Those who walked alone found themselves at the table sharing bread and wine until the time of the resurrection.