The Golden Age: what it is and who are its most important authors

Invoked over and over again as the most splendid stage of Spanish arts and literature, the called the Golden Age continues to ring in our ears as a unique moment in the history of Spain. Names such as Miguel de Cervantes, Lope de Vega, Calderón de la Barca or Francisco de Quevedo have been established as the great exponents of Spanish literature from the 16th and 17th centuries.

What exactly was the Golden Age? How many years does it cover? Who were its great protagonists? Is it true that the Spanish monarchy that saw him born was an empire already in clear decline?

In this article, we talk about one of the most famous and brilliant stages of Hispanic literature.

What is the Golden Age and where does the term come from?

The stage in which Spanish arts and letters acquired a brilliance never seen before is known as the Golden Age. In general, it is considered that this period of splendor began with the publication of the Castilian grammar by Antonio de Nebrija (1492) and ends with the death of the great Calderón de la Barca, which occurred in 1681.

However, its limits are not always clear, and even vary depending on the expert who analyzes it. Thus, for other authors the completion date would be none other than 1659, the year in which the Treaty of the Pyrenees and concluded with it the Spanish hegemony in Europe in favor of other nations, such as the France of Luis XIV.

On the other hand, the name Golden age it has not always been “canonical”. According to the literary critic Juan Manuel Rozas (1936-1896), the term appeared for the first time in 1736; Alonso Verdugo invoked it in his admission speech to the RAE, in clear parallelism with the Golden age of the human being (in which he lived peacefully with the gods), which Hesiod already sang in the jobs and the days and that Don Quixote himself recovers in Cervantes' novel.

A golden age that refers, then, to a time of splendor. It seems that from then on the idea began to spread (the following year we found the concept Century of Gold in the third chapter of the Poetics of Ignacio de Luzán), to end up consolidating at the end of the 18th century. In 1804, the enlightened writer Casiano Pellicer (1775-1806) included Calderón in the name, until then excluded from the Golden Age and, already in the XX, the inclusion of Luis de Góngora by the Generation of Poets of 27 takes place, completely fascinated by the beauty and innovation that his poetry.

- Related article: "The 8 branches of the Humanities (and what each of them studies)"

Son of a "decadent Spain"

One of the great clichés that surround the Spanish Golden Age is the idea that it was the result of a Hispanic monarchy in full decline. This is not accurate for various reasons; first, because, in truth, the beginning of the Golden Age occurs precisely in parallel with the rise of the Spanish monarchy (just with the first Austria, Carlos V), and continued throughout the 16th century with figures as preeminent in Spanish history as Felipe II. On the other hand, Hugh A. Huidobro demonstrated in his thesis The defensive strategy of the empire in the time of Felipe III (2017) that the myth of the reign of Felipe III as the starting point for the great decline is just that, a myth. In fact, and according to his research, the real decline of the Spanish empire did not come until much later, well into the eighteenth century.

It is true, however, that the Golden Age (which actually covers much more than a century) must be framed in a context of difficulties and social and economic conflicts. It is not a question of a "decadence" in the sense that it has traditionally been given, but it is true that Spain in the 17th century (the de Quevedo and Lope de Vega, among others) is a Spain afflicted by extremely high fiscal pressure and which presents sharp economic and social.

At the top of the social pyramid, the two privileged estates continue to exercise political dominance, the nobility and the Church, the owners of most of the land but who, on the other hand, account for only a minimal percentage of the population. The bulk of the population is made up of artisans, bourgeois, lawyers and, above all, peasants. It is a very unequal and bipolarized society, in which, in addition, religious differences and of ancestry: on the one hand, there are the old Christians, those who can prove several generations of family Christian; on the other, the descendants of converted Jews or Muslims.

The basic productive system is still an agriculture little or nothing adapted to the impressive population growth that occurred in the sixteenth century. On the other hand, the enormous military enterprises of the Habsburgs bleed the state treasury, until, At the beginning of the 17th century, the economic crisis erupted and materialized in a devaluation of the currency and an exorbitant increase in fiscal pressure.. That is the Spain that gives birth to the golden century of arts and letters: a monarchy that is still "glorious" on a military and political level, but in whose A great crisis is brewing inside that, on the other hand, many historians do not see as something isolated, but as part of the general regression that is taking place in Europe.

- You may be interested in: "The 5 ages of History (and their characteristics)"

Between the Renaissance and the Baroque

In the long century and a half that the golden age of Hispanic arts and letters lasted, specialists distinguish two basic periods: the renaissance stage and the baroque stage, to which a third could be added, the mannerist. As often happens, the limits of the different stages are not at all clear. Some authors, such as José Antonio Miravall (1911-1986), place the Baroque of the Golden Age in the 17th century (until Calderón's death), while others, such as Ángel del Río (1901-1962), expand their existence and locate their beginning around 1580, a century end that, on the other hand, coincides with the Mannerist expression in the Arts.

There is no doubt about the important role that the peninsular Renaissance had in the birth of this golden age of Hispanic culture. In this sense, It is essential to review the preponderant influence of universities such as those of Salamanca and Alcalá de Henares, as well as the poetry of Garcilaso de la Vega (1501-1536), the true promoter of Renaissance poetry in the Hispanic crown.

However, the main protagonists of the Golden Age cultivated a type of literature in a certain way "contrary" to Renaissance ideals; a literature that some authors have wanted to see as "anti-classical", for opposing the lofty idealism of the Renaissance. The 17th century is the century of the Baroque, a time of strong contrasts and harsh social criticism, in which, Although mythological and pastoral themes are still in vogue, a new meaning is often traced in them. It is the century of the picaresque novel (whose beginning we find in the lazarillo de tormes, by an anonymous author and published in the previous century), or popular plays (the “new comedy”), whose great exponent is Félix Lope de Vega (1562-1635).

The turn of the century and the new baroque airs accentuate the critical spirit of literature. In 1605 he appears The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quijote of La Mancha, by Miguel de Cervantes, a critic of society as "ingenious" as its protagonist, and who became so popular that, in 1614, Alonso Fernández de Avellaneda openly copied the character. An enraged Cervantes responds with the second part of his Don Quixote, published in 1615 and, for many, far superior to the first.

Realism is a key piece to understand the art and literature of the baroque world. We have already commented on how Cervantes carries out a dissection of society and its misery in his Quixote (and, by the way, a sharp criticism of chivalric novels and their idealism), as well as the adventures of Lázaro and Guzmán de Alfarache, the two “rogues” stigmatized by the misery and lack of opportunity characteristic of the time. Thus, the literature of the Golden Age becomes a vehicle for shaping the surrounding reality, testimony of the lights and shadows that that extravagant and pompous baroque supposes and, at the same time, disenchanted and contradictory.

The great literary genres in the Golden Age

Tradition has identified the Golden Age almost exclusively with Hispanic letters. Although the truth is that this golden age also extended to other artistic manifestations, such as painting and architecture, it was in the field of literature where this period of splendor acquired its greatest fame, and it is in this area where we will focus our description.

1. The poetry

Garcilaso de la Vega and his Renaissance sonnets are the banner of poetry from the first half of the 16th century. Later, and as the crisis and instability of the monarchy worsened, poetry gave way to a gradual abandonment of this idealization that the Renaissance implied. Many themes are still maintained (above all, those drawn from classical mythology) and some of the literary topics persist, although some new ones very characteristic of the Baroque are added, such as he Memento Mori and the Vanitas.

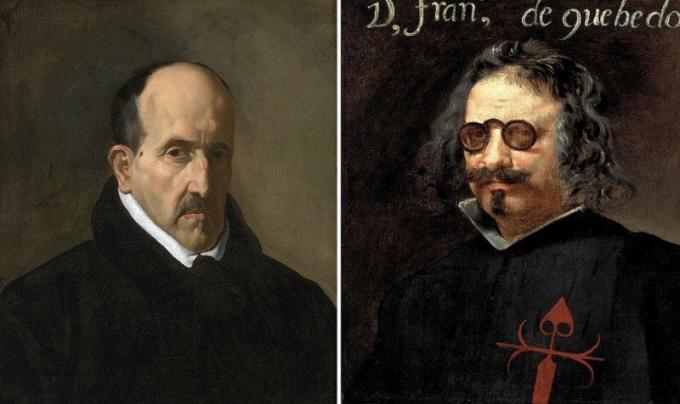

Broadly speaking, we can talk about two apparently irreconcilable currents, championed by two of the most distinguished poets of the Golden Age and who, if we believe the legend, were also irreconcilable. We talk, of course, about Luis de Góngora (1561-1627) and Francisco de Quevedo (1580-1645).

The first endorsed the trend that has come to be called culteranismo or gongorismo, which is characterized by the use of a language intricate, elaborate and excessive, as can be seen in one of his best-known works, The Fable of Polyphemus and Galatea (1612). Quevedo, for his part, displayed a poetry full of criticism and mockery, based on the somewhat far-fetched association of ideas, but much closer and understandable to the general public; the conceptual current.

2. The novel

Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra (1547-1616) is one of the most important authors, not only of the Spanish Golden Age, but also of universal literature.. His Quixote it has transcended borders and is considered a masterpiece of letters. Cervantes's work navigates between two centuries and two worlds; While some authors include it in Mannerism (the style of the final decades of the 16th century), others attribute a Renaissance style to it first and Baroque later.

Be that as it may, The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quijote of La Mancha It is, for many, the first modern novel in history. Considerations aside (since this point has been quite discussed), the truth is that the Spanish narrative has a before and after with the appearance of the Cervantine novel, since it constitutes a substantial departure from the style of novels that were then in vogue, the novels of chivalries. Not just a move away; Don Quixote is an authentic criticism of this type of narrative, as well as being a magnificent social satire.

On the other hand, we have already commented on the importance that, in a world pierced by social differences and economic, they acquire the picaresque novels, an authentic reflection of the misery of the classes lower. The picaresque novel uses the resource of the rogue, the great outcast of this Spain full of contrasts, to make a juicy satire of baroque society. To the already mentioned Lazarillo we have to add the seeker of Francisco de Quevedo (1580-1645) and Guzman de Alfarache, by Mateo Aleman (1547-1614).

- You may be interested in: "The 12 most important types of Literature (with examples)"

3. Theater

Needless to say; the Golden Age is the great century of the theater. What began in the 16th century as an entertainment show in the corrals (real animal pens, hence the name they later acquired spaces for the theater), continued in the 17th century with such important names as Félix Lope de Vega, who elevated this entertainment to the category of culture.

Lope de Vega is the great theatrical renovator of our literature. Not only did he break with the classical concepts of space and time, but he also made his characters speak in a popular language, far from the cultism that prevailed in the world of literature. Thus, from the hand of the playwright (who is estimated to have written some 400 plays), the Spanish theater acquired levels of excellence never seen before.

In Lope's extensive work (in which works such as Fuenteovejuna and El caballero de Olmedo stand out) we find the leitmotif of the time; the matter of honour. Many of his dramas revolve around a sullied matter of honor that must be avenged. This theme is collected by many other authors, such as Calderón de la Barca in his famous Mayor of zalamea. And it is precisely to the latter that we also owe the philosophical theater, more focused on moral and philosophical issues than on entertainment, whose greatest exponent is the well-known The life is dream. With Calderón's death the Golden Age of Hispanic letters came to an end.