Michelangelo Buonarroti: biography of the great artist of the Renaissance

Few discrepancies exist about the genius of Michelangelo Buonarroti, better known in Spanish as Miguel Ángel. Already in the colossal work of Charles de Tornay, his main biographer, in the title the author refers to him as "Painter, sculptor, architect". And perhaps to all this we should add the words "engineer" and "poet". Almost nothing.

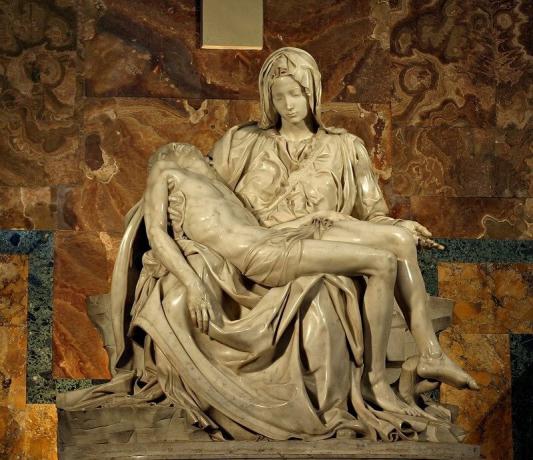

Michelangelo was a true man of the Renaissance, educated, very interested in the arts and with an unparalleled talent. Because there are few artists who have left us authentic masterpieces in various disciplines, and that is the case of Michelangelo. In the field of sculpture, his true vocation, there is little to say. He David, the Piety of the Vatican, the Moses. In architecture, nothing less than the dome of the Basilica of Saint Peter in Rome. And as for painting, a field in which he himself said that he was not sufficiently prepared, one only has to evoke the magnificent frescoes in the Sistine vault.

Join us on this journey through the life and work of the great genius not only of the Renaissance, but of the history of universal art.

Brief biography of Michelangelo Buonarroti

Michelangelo used to say (at least, this is how his biographer Ascanio Condivi reports it) that his passion for sculpture gave him He came because her wet nurse was the wife of a stonemason and, according to him, she had administered marble dust with her milk.

Anecdotes aside, the truth is that Michelangelo always considered himself, first of all, a sculptor. Despite this, he began his training in the workshop of Domenico Ghirlandaio (1448-1494), one of the most notable painters of Renaissance Florence, where his father had moved after the expiration of the by podesta that had taken him to Caprese, the town where our genius came into the world in March 1475.

The beginnings: under the protection of Lorenzo de Medici

Ludovico, Miguel Ángel's father, was not amused that his son wanted to dedicate himself to "manual arts", which was how fine arts were considered at the time. Let us remember that in the fifteenth century the medieval concept of the artist as just another craftsman, who earned his living with the work of his hands, was still in force. Ludovico, who despite living somewhat narrowly came from a patrician family in the city, could not allow one of his sons to dedicate himself to craft work.

However, that was the case, which increased the tensions that the artist had with his mother. We have commented that Michelangelo trained during his early adolescence in the Ghirlandaio workshop in Florence. It is the last decades of the 15th century, and the city is brimming with cultural splendor. The opulent Medici family was in command of the government of Florence and served as important patrons, especially the head of the family, Lorenzo the Magnificent (1449-1492).

Lorenzo de Medici was the protector of Michelangelo and, in many things, he behaved like a father to him. when the Magnificent died in 1492, Michelangelo suffered a severe blow, since he had lived during the last years in his house and had been educated in the famous sculpture garden that Lorenzo made available to young artists. There, Michelangelo not only had the opportunity to cultivate his innate talent, but was introduced to Florentine intellectual life and became he immersed himself in the philosophy and cultural environment of the city, which undoubtedly implied an important background that would help him in his production later.

The death of his supporter and the rise to power of the city of the obscure friar Girolamo Savonarola (by the way, coming from the same convent where Michelangelo's brother had professed his vows) turned the life of our genius upside down and left a permanent mark on his character.

- Related article: "What are the 7 Fine Arts? A summary of its characteristics"

The first stay in Rome

In the austere Florence that Savonarola proposed, the effervescent cultural life overshadowed by the harangues the friar's incendiaries, Miguel Ángel could only find an intellectual and artistic void that could in no way help you. So the young Michelangelo headed for Rome, a city that would be key to his development as an artist.

From this first stay are the Bacchus, which he made for Cardinal Riario (who did not like the work at all because it was "too sensual"), and the extraordinary Piety of the Vatican, which Michelangelo sculpted when he was only twenty-three years old. Commissioned by a French cardinal, the work shows a perfect mastery of both sculpture and composition..

The triangle formed by the mother and the son is compensated by the horizontal figure of the dead Christ, who he rests in the arms of a much too young Mary (remember that Jesus died at the age of thirty-three). With this, Michelangelo perhaps wanted to underline the virginity and purity of Mary.

There is an anecdote about the Pietà which, due to its curiosity, we must review here and which is collected by Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574) in his book The lives of the most excellent Italian architects, painters and sculptors. It seems that Michelangelo found out about the rumor that he awarded the magnificent piece to a certain Gobbio, a sculptor from Milan. He was filled with anger, at night he carved his name on Maria's belt. True or not, the truth is that the Pietà is the only work by the artist that is signed and, if we consider his difficult and angry character, we can consider that there may be some basis in the anecdote of reality.

- You may be interested in: "History of Art: what is it and what does this discipline study?"

Return to Florence and execution of David

Despite the success achieved with his Piety, Michelangelo's goal was to secure a papal commission during his stay in Rome. Not getting it, he returned to his family's town. Savonarola had fallen from grace and had been executed in 1498, so Florence returned to what it had once been: a city full of cultural effervescence..

It was the year 1501, and the city needed an element that would express the character of the Republic. The idea was to sculpt a figure of David, the biblical hero, from a single block of marble that had been kept in the Duomo for years. The company was very difficult, since the block was very narrow, which made it difficult to execute the proportions correctly.

Everyone knows that Miguel Ángel achieved his goal, and with a vengeance. The result was the sculpture of the David, possibly the best known of the artist and which became a symbol of the Florentine Republic, embodying courage and strength. Michelangelo does not represent David after bringing down the giant Goliath, as Donatello does in his homonymous sculpture, but rather that he presents it just before the confrontation, focused on his mission. Hence the frown and intense look of the young man, a true expressive feat that gives us an idea of the genius of its author.

Much has been said about the deformities anatomical features of the hero's body. Indeed, the head is too big, as well as its hands and feet. Some experts relate these errors to the narrowness and size of the block offered to the artist, without tell that a half-sketched figure already existed, which did not give the artist many options when it came to executing the David.

On the other hand, we must take into account that the sculpture had to be placed, in principle, at a considerable height, in one of the buttresses of the Duomo, so Miguel Ángel perhaps wanted to correct the possible optical deformations that this would cause. This theory, however, does not seem plausible, since it would not explain the disproportion of the feet. Be that as it may, the David represents one of the creative peaks of the Florentine genius.

- Related article: "The 8 branches of the Humanities (and what each of them studies)"

Second stay in Rome: The Sistine Chapel

Michelangelo's second stay in Rome meant the achievement of the objective of the first: obtaining a papal commission. The then pontiff, Julius II, entrusted the artist with the execution of his tomb. This was to be Michelangelo's great work, for which he worked conscientiously with the monetary advance he had received. He went to the Carrara quarry to personally supervise, as he always did, the choice of marble, the transfer of it to Rome and the storage of it.

But, unexpectedly, Julius II abandoned the idea of the sepulcher and decided to entrust Bramante (1444-1514) with the reform of the Basilica of Saint Peter. Michelangelo, enraged and in debt over the preparations for the tomb, flees Rome, in a dramatic gesture that has caused rivers of ink to flow about the bad relationship between the pope and the artist.

Leaving aside the legend, it is true that the personalities of these two characters, although similar in many ways, were violently similar in terms of character and determination. In the end, Julio II ends up commissioning the Florentine the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel vault; according to Vasari and Condivi, spurred on by Bramante, eager to promote the career of young Rafael. If this story is to be believed, Bramante did not believe Michelangelo capable of doing the frescoes, and wanted the pope to commission him the work only to see his rival fail.

Be that as it may, Michelangelo took charge of the great enterprise despite his initial protests, since he considered himself a sculptor, not a painter. Julius II's initial project was to represent the twelve apostles, but the iconography that ended up prevailing was motifs from the Old Testament: the Creation of Adam and Eve, the expulsion from Paradise, the sibyls and the prophets, among others.

Michelangelo's creative process was not always satisfactory. The artist began work on the Sistine in January 1509, with the execution of the universal deluge, and he continued to work on the frescoes until October 1512, to the despair of the pope, who wanted Michelangelo to paint faster. The artist's working position, lying on his back on the scaffolding, was fatal to his physical health, and the fact that he worked at night, by candlelight, aggravated his vision problems. The great work of Michelangelo had completely devoured him.

tireless worker to death

The papal tomb project was not entirely abandoned. Once Julius II died, Saint Peter a Medici ascended to the throne, who took the name of Leo X, a pontiff also an art lover but who preferred the work of Michelangelo's great rival, the young Raphael Sanzio.

However, Leo X managed to get the della Roveres, the family to which the late pope belonged, to commission a new project from Michelangelo. On this occasion it would be a funerary monument of smaller dimensions and, unlike the temple free-standing projected during the life of Julius II, this would be attached to the wall of the church of San Pietro in Vincoli.

For this new tomb Michelangelo carved his other masterpiece, the Moses, who gained immediate fame and he served as a model for many European sculptors of the time. Also for this project he started working on his slaves. Most of them were unfinished, which still gives them a more mysterious and fascinating aura, since it seems that the figures are trying to "escape" from the block.

Those years were troubled for the artist. In 1534 Ludovico, his father, died. Two years earlier, Michelangelo had met Tommaso Cavalieri, a much younger nobleman who awakened a deep and intense passion in the mature sculptor, if we take into account his correspondence. It is known that Michelangelo had no love affair (known, at least) until then, which raises some questions: was Michelangelo homosexual? Also known is his intellectual relationship with Vittoria Colonna, for which he came to compose beautiful sonnets. Maybe he was bisexual, or Vittoria just represented an ideal? Be that as it may, we have to remember that, at that time, homosexuality was punishable by death, so, if it were, Miguel Ángel had to be very careful that it did not spread.

The last great works of Michelangelo were to be the Medici Chapel, in the New Sacristy of the church of San Lorenzo, the Laurentian Library and the colossal Last Judgment of the Sistine, executed more than two decades after the frescoes of the vault. Miguel Ángel paints various groups as if suspended in a space without form or time, presided over in the center by the spectacular figure of Christ, with a very careful and forceful anatomical study, as was characteristic of the work of the Florentine. To his right, The Virgin withdraws in a gesture that seems to be in pain or fear. As Charles de Tolnay comments, his body is reminiscent of the fold of classical curled-up Venuses. Taken together, the painting is so powerful that the viewer is instantly captivated by what appears to be a sublime vision.

Constant and tireless worker, incorrigible perfectionist, Michelangelo Buonarroti was creating until the end of his life. It is known that a few days before he died, he was busy with the Piedad Rondanini, his last masterpiece, which remained unfinished. The genius died in Rome in February 1564, when he was about to turn eighty-nine, and was buried in Florence, the city of his youth. That same year, the Congregation of the Council of Trent ordered to cover the "sinful" nudes of the Sistine.