Caspar David Friedrich: biography of this Romantic painter

Norbert Wolf collects in his book dedicated to Friedrich the impression that the romantic painter had on one of his visitors, the Russian poet Vasili Andreyevich Shukowski, who said of him that, although his landscapes seemed to betray a melancholic person, this image did not correspond to the reality.

While we may believe that Caspar David Friedrich was not perennially in the typical romantic gloom, we also cannot fully trust Shukowski's view, since we know from some of his contemporaries that the painter attempted suicide on some occasion and that his character tended (and, above all, in his last years) to depression and isolation. A true character of Romanticism.

In this biography of Caspar David we will try to sketch a portrait of the life and work of this charismatic artist., one of the greatest exponents of the romantic movement in painting.

Brief biography of Caspar David Friedrich, the great painter of German Romanticism

Although when Friedrich was born in September 1774 his hometown of Greisfwald belonged to the Swedish crown by virtue of the Thirty Years' War, the region was culturally German. Let us remember that then the German territories were a mosaic of states that, at that time and by virtue of pre-romantic movements such as the

Sturm und Drang, they began to become aware of his national identity.Caspar David Friedrich was one of the great standard-bearers of the romantic movement in the pictorial field, who took landscape painting to levels of symbolism and spirituality never seen before. However, and as always, his work did not start from scratch. The artist was obviously influenced by Dutch and British landscape painters, especially John Constable (1775-1837), the great leader of English landscape painting.

- Related article: "History of Art: what is it and what does this discipline study?"

An early experience of death

Romanticism is not understood without death. The romantics felt for her a kind of admiration tinged with fear, an often morbid emotion that peppered practically all of her work. Friedrich was no exception; especially in his late works, when he was already very ill, we see an evident obsession with the subject, whose main expression is the disturbing Landscape with grave, coffin and owl, executed around 1836, just four years before her death.

But Friedrich not only made love to death because of his adherence to the romantic movement. He had felt her very close since her earliest childhood: in 1781, when she was only seven years old, her mother, Sophie Dorothea, died, and he and his five siblings passed into the care of a housekeeper, the endearing Mother Heiden, for whom Friedrich would always profess great affection.

The deaths did not stop here. One year after the death of her mother, Elizabeth, one of her sisters, died of smallpox. Later, in 1791, another of the girls, Maria, would succumb to typhus. But probably the death that most impacted the sensitive spirit of the little one was that of his brother Johann Christoffer, who died in the winter of 1787 while trying to save Friedrich, who had fallen into the ice. The guilt that the artist would carry with him throughout his life contributed, and not a little, to his constant attacks of melancholy and, more than likely, to his suicide attempts.

- You may be interested in: "What are the 7 Fine Arts?"

The arrival of success in the world of art

Friedrich's first successes come in the 1810s. Before, however, he had studied drawing at the University of Greifswald with the famous professor Johann Gottfried Quistorp and later moved to Copenhagen to continue studying at his academy. It is in the Danish city where he executes his first watercolor, Landscape with gazebo (1797), inspired by English gardens and in which echoes of a distant Rococo style still resonate.

It was Thomas Thorild, a Swede who held the chair of Literature and Aesthetics at the University of Greifswald, who taught the young Friedrich to distinguish between an external vision (that is, the one that captures the real forms of a landscape) and the internal one, much more related to the psychic and spiritual state of the observer. This is important, since Friedrich's landscapes will not be conventional landscapes at all; the painter impregnates his views with a whole symbology and a meaning that goes beyond mere appearance.

In 1808, the artist executes what will be one of his great works: The cross on the mountain, also known as The Tetschen altar. Baron von Ramdohr, who saw the work in Friedrich's studio, lashed out hard at it, criticizing its lack of perspective and depth, as well as its excessive stylization. What von Ramdohr criticized was precisely what made this painting an apotheosis of the new German romantic painting, since The Tetschen altar he is inevitably reminiscent of a Gothic altarpiece.

The Napoleonic invasions had spurred anti-French and anti-classicist sentiment among the Germans, and Friedrich was no exception. In fact, and as noted by Norbert Wolf, it is plausible that The Tetschen altar It was, at first, a patriotic and non-religious work, and that only after certain vicissitudes did he end up decorating the altar of a church.

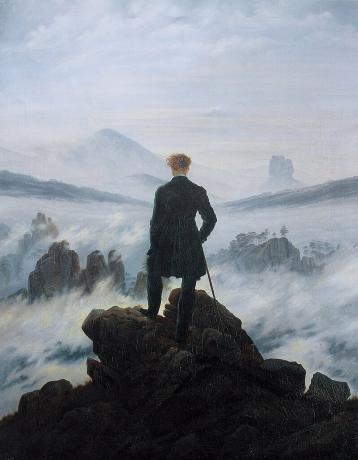

Be that as it may, that year marks the beginning of success for Friedrich. First, because The cross on the mountain he placed his name on everyone's lips; second, because that same year he performs one of his masterpieces, the famous monk by the sea, an authentic hymn to romantic spirituality and the contemplation of the sublime.

In a similar way to his later painting Traveler contemplating a sea of clouds (1818), Friedrich here confronts the human being with the immensity of nature, before which the character inevitably dwarfs. However, there are clear differences between the two paintings: while, in the second, the man occupies a large part of the painting, in the first the monk is practically a tiny point that can barely be glimpsed between the expansion of the sea and the darling.

- Related article: "The psychology of creativity and creative thinking"

Caroline Bommer, muse and fellow lover

Perhaps the much larger size offered by the walker in the sea of clouds is due to the change that occurs in the life trajectory of the painter.

That same year, 1818, he married Caroline Bommer, a smiling twenty-five-year-old (Friedrich is already forty-four) that seems to shed a placid light on the existence of the tormented artist.

This can be verified if one observes the work of this period, where the canvases become more bright and cheerful and, above all, human figures begin to proliferate, especially those feminine. Critics attribute this change to the painter's happy union with Caroline that, despite having “disrupted his life” (in a letter Friedrich comments on how he has changed his life as a hermit) it has given a positive direction to his existence.

Caroline appears in numerous works by Friedrich from the 1810s and 1820s. We see it, for example, in the famous Woman before the exit (or) sunset, made around 1820. Caroline appears on the canvas from behind, bathed in warm solar rays, which cannot be discerned if they belong to dawn or twilight. Both versions are plausible; a sunrise would make sense if we consider the figure as a kind of prayer from the Christian era primitive, but the sunset version would correspond perfectly with the idea of death, so constant in Friedrich. The path suddenly cut off before the young woman would consolidate this last hypothesis.

Another of Friedrich's famous works in which his wife appears is Cretaceous rocks on Rügen (1818), inspired precisely by his honeymoon. Three characters (with their backs turned, as is usual in the painter's work) look towards the void that opens before them, as they are on the edge of a beautiful white cliff. Beyond, the sea unfolds eternal and immutable, also an important leitmotiv in Friedrich's work as a symbol of life and the journey towards death. The three characters would be Caroline, the artist and his brother, Christian, who had accompanied them on the trip.

Also at this time male figures begin to proliferate as a couple, reflecting their closest friendships (especially with Carus and Johann Christian Clausen Dahl, a Norwegian-born painter who became his neighbor in Dresden and livened up his existence with her sympathy and his evening chats). It's the time of paintings like Two men watching the moon (1819-20), Man and woman contemplating the moon (1824) and Sunset landscape with two men (1830-35).

Since the Congress of Vienna (1814-15) and the restoration of the Old Regime, Friedrich's work had become, in a way, more withdrawn and intimate. After the “luminous” years of his first years of marriage with Caroline, the artist's character began to sour, and around 1830 he fell back into melancholy. His works no longer interest anyone beyond his circle.

Last years and death

In 1824 an illness overtook him that prevented him from painting in oil for a few years, which did not help to improve his condition. In 1835, a stroke left him temporarily immobilized in his arms and legs, which greatly affected his work. The disease accentuates his depression and his obsession with death, that old friend who has accompanied him since his early childhood, which leads him to carry out numerous works on cemeteries: cemetery in the snow, from 1826, with an open grave in the foreground that connects with the morbid obsession of his own departure; the gate of the cemetery (1825-1830) and, above all, the entrance to the cemetery (1825), where we can see a couple looking at the small tomb of his son, over which winged figures fly over which, at first, are barely perceptible.

The same year that the disease came into his life, he executed a work that is practically considered his masterpiece, but which during the painter's lifetime had so little success that it could not even be sold. Is about the icy ocean, whose surprising modernity leaves us completely amazed. Inspired by the shipwreck of a ship in the ice, the canvas only reveals the tiny keel of the ship, camouflaged among the huge solid blocks of ice. It is not necessary to be very perceptive to realize the connection that this work maintains with the great torment of Friedrich's existence: the death of his brother, drowned precisely in the ice. the icy ocean It is, therefore, a kind of living testament, an exorcism with which the painter intends to remove the pain that he has accumulated during his life.

Friedrich's mental state worsens by leaps and bounds. Some witnesses speak of mistreatment of his wife, whom he accuses of being unfaithful. Shukowski's friend, of whom we have already spoken, visits him a few months before he died, and affirms that his condition was lamentable and that the painter began to cry in his presence. Friedrich finally died on May 7, 1840; his work will not be recognized again until almost a century later.