7 examples of Art of the First Civilizations

Art has always been linked to human beings. As far as we know, there is no other living being that is capable of creating, so human artistic manifestations are unique. Since human beings have existed, they have tried to capture, in all possible media, a series of concerns, fears and desires or, simply, the beauty that surrounded them.

There is a lot of talk about the art of the Renaissance, the 19th century, the avant-garde... but What about the art of early civilizations? How did people create in ancient Sumeria, in Babylon, in India, in Egypt? In today's article we bring you some of the first masterpieces of humanity. We hope you enjoy them.

7 examples of art from the first civilizations in Antiquity

From the votive figurines of Sumerian cities to the colossal winged creatures of the Babylonian culture, passing through the fascinating Egyptian civilization and the rich culture of the Valley of the Indo. Join us on a brief journey through 7 of humanity's first works of art.

1. The seated statuette of Gudea (Sumer, 3rd millennium BC. C.)

The Sumerian civilization was the first great civilization of Eurasia, where the beginning of the entire history of humanity is commonly located. And although this idea is still linked to the usual Eurocentrism that existed in the 19th century, it is true that In the valley of the Tigris and Euphrates we can find some of the oldest artistic manifestations.

From Sumer comes cuneiform writing, one of the first known writing systems, which spread to the other Mesopotamian lands and served for the administration and literature not only of the Sumerians, but also of Babylonians. On the other hand, the Sumerian pantheon powerfully influenced the religion of adjacent cultures, so it is not an exaggeration to say that Sumer was the origin of the Mesopotamian civilization.

The example in question must date back to the 3rd millennium BC. C., in the time of a king (pathesi) known as Gudea, lord of the Sumerian city-state of Lagash. It is a small statuette (46 x 33.2 cm), made of black diorite and showing obvious hieraticism. Gudea is represented sitting on his throne, with his hands together and gathered in a prayerful attitude (very common in human representations from Sumer). In fact, in the cuneiform stele that we can see on Gudea's tunic it is said that the work is an offering to a divinity. The anatomy is poorly identified and obeys more of an idealization than a real representation.

This seated figurine is not unique; We know more than twenty representations of this patesi or monarch, in addition to other representations of praying people. This statuette in question is currently kept in the Louvre Museum.

- Related article: "Art History: what is it and what does this discipline study?"

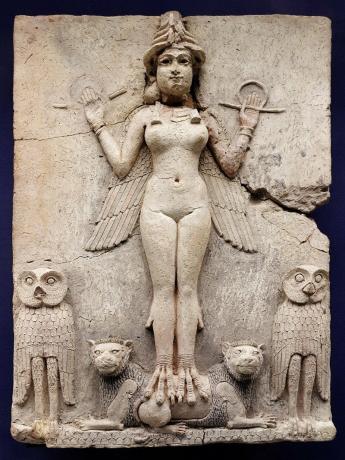

2. The Queen of the Night or Burney Relief (Babylon, 2nd millennium BC. C.)

This impressive and beautiful relief dates from the time of the Paleo-Babylonian empire, a stage in the history of Babylon that we must date to the 2nd millennium BC. c. Babylon occupied what is now Iraq and the surrounding territories (expanding into Akkad and Sumeria), and its power did not diminish until its annexation to the Achaemenid Persian empire of Cyrus the Great (6th century to. C.).

The relief known as Queen of the night Or simply, Burney relief It is a small terracotta relief that shows an enigmatic naked woman, whose feet are eagle claws resting on two majestic lions. There are serious doubts about the identity of the person represented: in all likelihood she is a goddess, but experts are considering three divinities as possible candidates. The first, Ishtar, the goddess of love, sex, fertility and war, who the Sumerians called Inanna and the Phoenicians, Astarte. The identification of her with Ishtar is quite probable given the lions on which the deity rests her claws, an animal-symbol of the goddess.

The second possibility is Ereshkigal, a Mesopotamian goddess linked to the underworld. Similar to the Greek Persephone, she was kidnapped by a monster from the underworld, and since then she rules the depths with her husband Nergal. The two owls that escort her could corroborate this identification of hers, since they are nocturnal animals, related to the world of the dead. The downward-turned wings that the goddess presents would also give a clue to her status as an earthly goddess, and not a celestial one, as Ishtar would be (of whom, by the way, Ereshkigal is her sister).

Finally, a final possibility identifies the enigmatic goddess as Lilitu, a creature from the underworld, which the Hebrews incorporated into their mythology as Lilith, Adam's first wife.

3. Fresh from the Taurocatapsia (Crete, 2nd millennium BC. C.)

The Minoan civilization, installed on the island of Crete around the 3rd-2nd millennium BC. C., was one of the most prosperous, richest and refined in the Mediterranean. Its manufacture was sold throughout the European continent and, of course, reached the lands of Mesopotamia. On the other hand, her art, cheerful and brightly colored, powerfully influenced Mycenaean art and primitive Greek art.

The Taurocatapsia is a dry wall painting located in the ostentatious palace of Knossos, the capital, and currently preserved in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum. These are several layers of painted stucco that represent acrobats at the moment of practicing the famous “jump into the sky.” bull”, a very typical activity of the Minoan culture and which was related to the sacredness of the bull in the area Mediterranean.

The animal occupies the center of the painting; Its sinuous but eminently stylized silhouette seems to capture the restless movement of the bovid, spurred on by the three human figures that surround it. On both sides we see two light-skinned characters, probably women (since, in a similar way to what As the Egyptians did, the Cretans differentiated the sexes in their paintings through the tone of the fur); They are shown practically naked, so that their clothes do not interfere with the dance. On the other hand, we see a male character jumping on the animal's back, in a forceful and majestic acrobatic moment.

- You may be interested: "The 6 stages of Prehistory"

4. The bust of Nefertiti (Egypt, around 1345 BC. C.)

It is probably one of the most remembered works of ancient Egypt. The really paradoxical thing is that the bust of Nefertiti does not present the typical characteristics of Egyptian art, as it is framed in a time (the Amarna period) in which both she and her husband, Pharaoh Akhenaten, undermined the foundations of the culture of her country and renewed it culturally and spiritually.

In fact, the artistic production that was carried out under the reign of Akhenaten is included in a subperiod of the Egyptian style, the Amarna or Amarnian style. The main difference with respect to the artistic tradition of the Nile country is its greater naturalism, which often falls into a certain ridicule of forms or, at the very least, their exaggeration. Famous are the cases of the portraits of the pharaoh, who is represented with a bulging belly and loose flesh, as well as with pronounced and almost caricature-like features.

This is why the bust of Nefertiti stands out for its elegant beauty. It was found in the city of Akhetaten, among the remains of the sculptor Tutmose's workshop, making it the only Egyptian sculpture of which we know the author. The queen is represented in all her splendid beauty, with her long swan neck, her full red lips and her discreet makeup. If we are guided by the date (around 1345 BC. C.), Nefertiti would have been about forty years old when Thutmose made her portrait, so it is very likely that the artist “retouched” her features to make her look younger and more beautiful.

5. Ashoka's capital (India, s. III a. C.)

The Mauryan period is one of the most splendid in the Indus Valley, when the arts flourished under the impulse of the new religion, Buddhism. Under the reign of Ashoka, the so-called “Ashoka pillars” proliferated., a series of pillars spread across northern India of which we currently only preserve barely twenty.

One of the most famous is the one known as “Ashoka's capital”, in the city of Sarnath, one of the four sacred cities of Buddhism as it is the city where Buddha preached for the first time. There is a capital formed by four lions that join together at the back, and place their paws on a base where various animals are captured in a beautiful frieze. All of this rests on a lotus flower.

One of the most accepted interpretations is the reading of the capital as the plastic embodiment of Buddhist enlightenment: the lotus would be our earthly world, while the animals that “turn” in the frieze would be samsara, the eternal wheel. Finally, the four lions could be representing Buddha, although they could also be the four truths of Buddhist philosophy.

The capital is carved from a single block of sandstone, and the original is currently preserved in the Sarnath Museum.

6. The Terracotta Warriors (China, s. III a. C.)

This impressive funerary complex is one of the most spectacular not only in China, but in universal art. Promoted by Emperor Qin Shi Huang, the first of the Qin dynasty (3rd century BC). C.), is a set of more than 6,000 figures, both soldiers and horses, that make up an authentic imperial army.

Discovered in the early 1970s by local farmers, It is a funerary monument to the emperor, whose tomb is located one and a half kilometers away.. The figures are distributed in several graves. The third of them would correspond to the General Staff, since figures of generals are buried there. The warriors are arranged in battle formation, and include archers, spearmen, cavalrymen, in addition to figures not related to war, but rather to entertainment: acrobats, dancers or swans.

But the most surprising thing about this work is not its size (already astonishing in itself), but the scrupulous individualization of the characters. Because each of the soldiers has personalized features, as well as careful war equipment that, due to its detail, allows military ranks to be differentiated. The material is terracotta, but it is known that they were glazed in different colors which, unfortunately, have been almost completely lost.

7. The sarcophagus of the spouses (Etruria, Italy, 6th century BC. C.)

The Etruscans are an enigmatic people, despite the fact that a large part of Roman culture comes from them. Its origins are unknown; It is known that they lived in the part of Italy that now corresponds to Tuscany, and that they were a sophisticated people and great lovers of luxury. Likewise, the Etruscans attached great importance to funeral rituals, as attested to by one of the funerary jewels that we have left. this culture: the one known as the “sarcophagus of the spouses”, from the Cerveteri necropolis and which is currently preserved in the Louvre.

The sarcophagus, more than one meter high and almost two meters wide, is actually a funerary urn, where the ashes of the deceased were kept. In this case, it is a marriage, which we see represented in the magnificent sculpture that adorns the sarcophagus. The deceased are not depicted in a recumbent and sleeping position, as is common in medieval tombs, but rather they are shown to us alive., actively participating in a banquet; probably, at his own funeral agape.

The artist has represented in a very detailed way the busts and faces of the deceased (despite the marked hieraticism and their facial features). archaic, which show the typical Etruscan smile), very much in contrast to the legs, which seem “crushed” against the lid of the sarcophagus. In any case, it is one of the best examples of funerary art from ancient Etruria, which also attests to the concept post-mortem that this Mediterranean civilization had.