The Garden of Earthly Delights, by Hieronymus Bosch: history, analysis and meaning

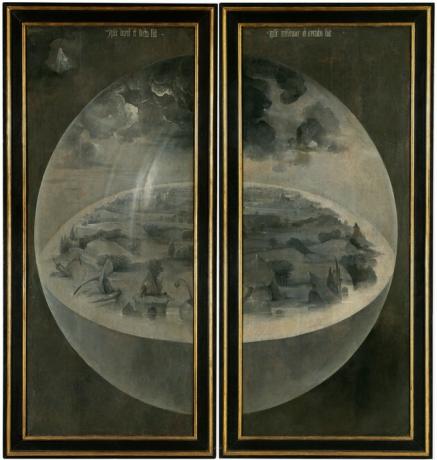

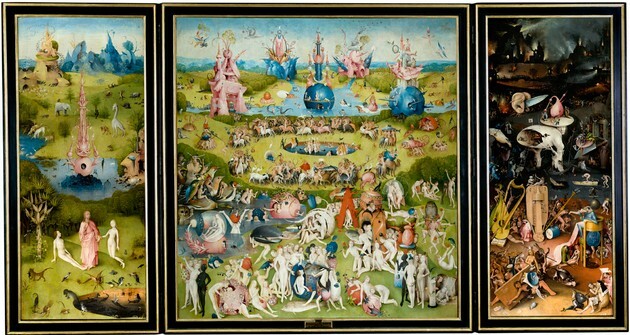

The Garden of Earthly Delights It is the most emblematic and enigmatic work of Bosco, a Flemish painter. It is a triptych painted in oil on oak wood, made around 1490 or 1500. When it remains closed, we contemplate two panels in which the third day of creation is represented. When opened, the three interior panels represent paradise, earthly life (the garden of earthly delights) and hell.

His way of representing these themes has been the subject of all kinds of controversy. What was the purpose of this work? What was it intended for? What mysteries are hidden behind this piece?

Animation of the Museo Nacional del Prado (detail).

Description of the closed triptych

When the triptych is closed, we can see the representation of the third day of creation in grisaille, a pictorial technique in which a single color is used to evoke the volumes of the relief. According to the Genesis account, a fundamental reference in the time of Bosco, God created vegetation on Earth on the third day. The painter thus represents the land full of vegetation.

Technique: grisaille. Measurements: 220 cm x 97 cm in each panel.

Along with this, Bosco seems to imagine the world as it was conceived in his time: a flat Earth, surrounded by a body of water. But strangely, Bosco surrounds the Earth in a kind of crystal sphere, foreshadowing the image of a round world.

God watches from above (upper left corner), at a time that seems to be, rather, the dawn of the fourth day. Creator God wears a crown and an open book in his hands, the scriptures, which will soon come to life.

On each side of the board, a Latin inscription of Psalm 148, verse 5 can be read. On the left side it reads: "Ipse dixit et facta sunt", which means 'He said it himself and it was all done'. On the right side, 'Ipse mandavit et creata sunt', which translates as 'He himself ordained it and everything was created'.

Description of the open triptych

When opening the triptych in its entirety, we are faced with an explosion of color and figures that contrasts with the monochrome and inanimate character of the creation.

Some scholars have seen in this gesture (revelation of the internal content of the piece) a metaphor for the process of creation, as if somehow El Bosco introduced us to a complicit look at the natural and moral evolution of the world. Let's see which are the main iconographic elements of each panel.

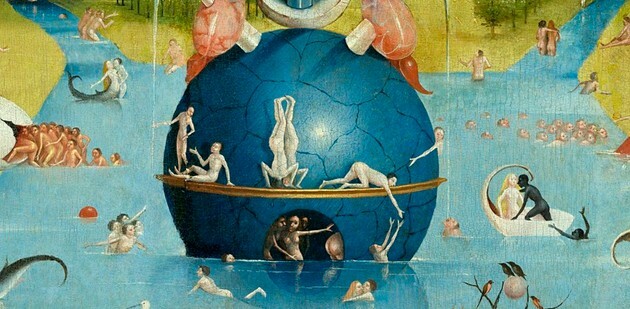

Paradise (left panel)

Oil on oak wood. Measurements: 220 cm x 97 cm.

The left panel corresponds to paradise. In it you can see the creator God with the features of Jesus. He holds Eve by the wrist, as a symbol that she gives it to Adam, who lies on the ground with his feet superimposed on the ends of it.

To the left of Adam, is the tree of life, a dragon tree, an exotic tree typical of the Canary Islands, Cape Verde and Madeira, which El Bosco could only know through graphic reproductions. This tree was formerly associated with life, as its crimson juice was believed to have healing properties.

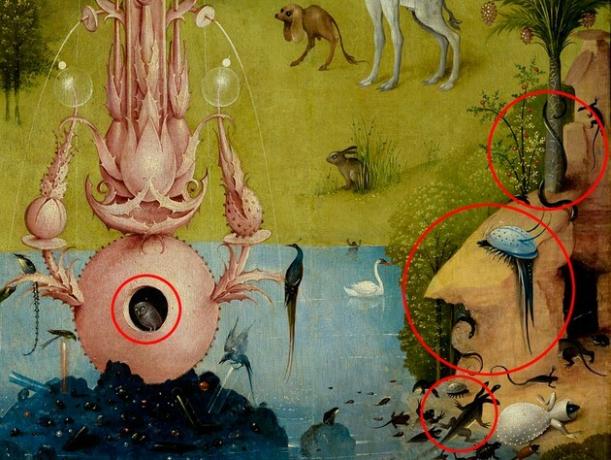

In the central strip and to the right, is the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, surrounded by a snake. It lies on a rock with a humanoid profile, probably a symbol of hidden evil.

Under the rock, we see a series of reptiles emerging from the water and adopting extraordinary forms. Can this be understood from the perspective of the evolution of species? It is one of the questions that experts ask themselves. Could Bosch have imagined a preview of evolutionary theory?

Below, the rock with human features. In the lower right corner, the evolution of reptiles.

In the center of the piece, an allegorical fountain stands out to the four rivers of Eden that vertically crosses the space like an obelisk, symbol of the source of life and fertility. At its base, there is a sphere with a hole, where you can see an owl that contemplates the imperturbable scene. It is about the evil that haunts the human being from the beginning, awaiting the time of damnation.

Between the fountain and the tree of life, over the lake, a swan can be seen floating. It is a symbol of the spiritual brotherhood to which Bosco belonged and, therefore, a symbol of brotherhood.

Throughout the entire scene you can see all kinds of sea, land and flying animals, including some exotic animals, such as giraffes and elephants; we also see fantastic beings, such as the unicorn and the hippocampus. Many of the animals are fighting.

Bosco had knowledge of many natural and mythological animals through the bestiaries and travel stories published at the time. This is how he had access to the iconography of African animals, for example, illustrated in the diary of an Italian adventurer known as Cyriacus d'Ancona.

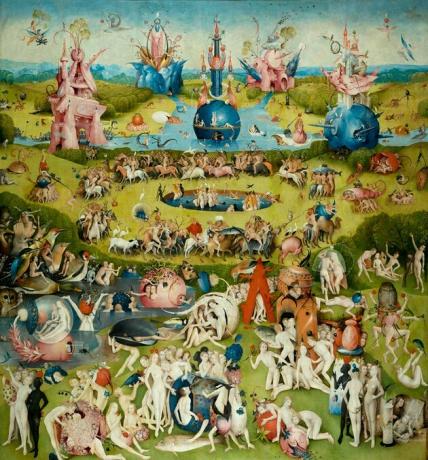

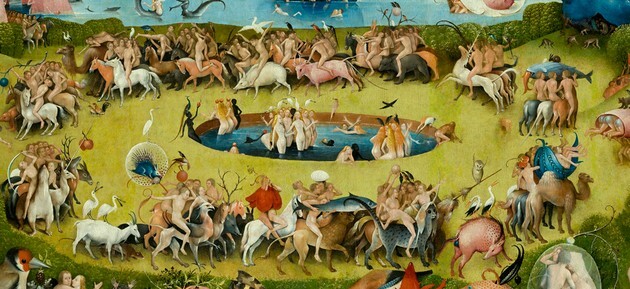

The Garden of Earthly Delights (central panel)

Oil on oak wood. Measurements: 220 x 195 cm.

The central panel is the one that gives the title to the work. It corresponds to the representation of the earthly world, which is symbolically referred to today as "the garden of earthly delights."

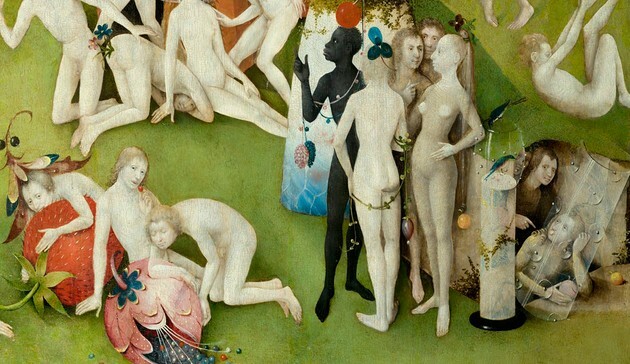

In this one, dozens of totally naked, black and white people are represented. The characters are distracted while enjoying all kinds of pleasures, especially sexual ones, and are unable to see the fate that awaits them. Some characters look at the audience, others eat fruit, but, in general, they all converse with each other.

For the time of the painter, nudity in painting was unacceptable, except that it was the representation of mythological characters, such as Venus and Mars and, of course, Adam and Eve, whose ultimate goal was sobering.

Thanks to the somewhat more permissive environment of the Renaissance, devoted to the study of human anatomy, Bosco is not afraid head-on depicting the nudity of ordinary characters, but of course justifies it as an exercise moralizing.

There are common and exotic animals, but their sizes contrast with the known reality. We see giant birds and fish, and mammals of varied scales. Vegetation and, especially fruits of enormous sizes, are part of the scene.

The strawberry tree will, in fact, have a recurring appearance. It is a fruit that was considered capable of getting drunk, since it ferments in the heat and its excessive consumption generates intoxication. Strawberries, blackberries and cherries are other fruits that appear, associated with temptation and mortality, with love and eroticism respectively. Apples, a symbol of temptation and sin, could not be left out.

In the upper strip of the composition and in the center, there is an allegory to the fountain of paradise, now cracked. This font completes a total of five fantastic constructions. Its fractures are symbolic of the ephemeral nature of human pleasures.

In the center of the plane, you can see a pool full of women, surrounded by horsemen riding all kinds of quadrupeds. These groups of horsemen are associated with capital sins, especially lust in its different manifestations.

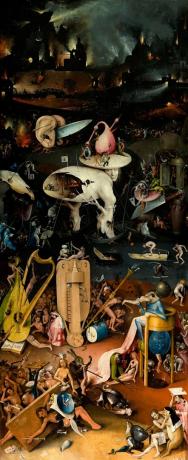

Hell (right panel)

Oil on oak wood. Measurements: 220 cm x 97 cm.

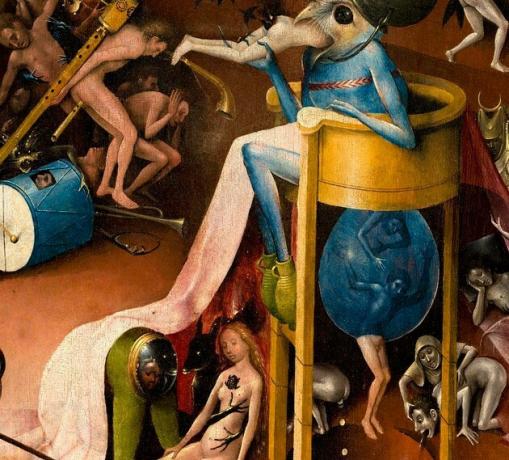

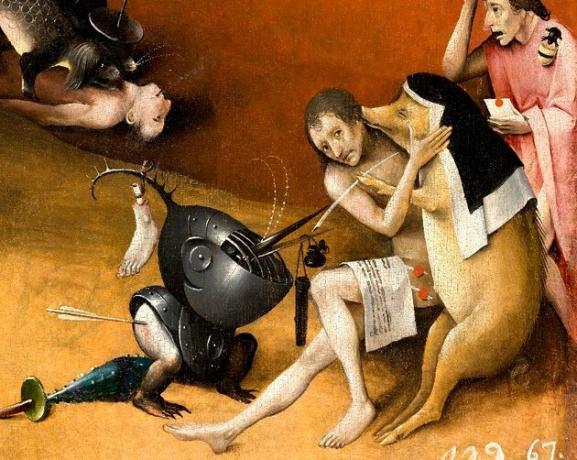

In hell, the central figure of the man-tree stands out, who is identified with the devil. In Hell, this appears to be the only character looking towards the viewer.

In this section, people get their due for sins committed in the garden of earthly delights. They are tortured with the same elements that they enjoyed in the garden of earthly delights. Bosco here condemns gambling, profane music, lust, greed and avarice, hypocrisy, alcoholism, etc.

The prominence of musical instruments used as torture weapons has earned this panel the popular name of "musical hell".

Likewise, hell is represented as a space of contrasts between extreme heat and cold. This is because in the Middle Ages there were several symbolic images of what could be hell. Some were associated with eternal fire and others with extreme cold.

For this reason, in the upper part of the Hell panel, we see how multiple fires fall on the souls in distress, as if it were a scene of war.

Just below the man-tree, we see a scene of extreme cold, with a frozen lake on which skaters dance. One of them falls into the winter water and struggles to get out.

Analysis of the work: imagination and fantasy

In an engraving by Cornelis Cort with the portrait of Bosco, published in 1572, an epigram by Dominicus Lampsonius can be read, whose approximate translation would be the following:

What do you see, Jheronimus Bosch, your astonished eyes? Why the paleness on his face? Have you seen the ghosts of Lemuria appear or the flying specters of Erebus? It would seem that before you the doors of the miser Pluto and the dwellings of Tartarus have been opened, seeing how your right hand has painted so well all the secrets of Hell.

With these words, Lampsonius announces the amazement with which he admires the work of Bosco, in which the subterfuges of the imagination exceed the canons of representation of his time. Was Bosch the first to imagine such fantastic figures? Is his work the result of a single thought? Would anyone share such concerns with him? What did El Bosco want with this work?

Certainly, the first thing that strikes us when we see this triptych is its imaginative and moralizing character, expressed through elements such as satire and mockery. Bosco also uses multiple fantastic elements, which we could call surrealbecause they seem taken from dreams and nightmares.

If we think of the great Renaissance painting we are used to (sweet angels, saints, Olympian gods, elite portraits and historical painting), this type of representation calls the attention. Was Bosch the only one capable of imagining such figures?

While easel painting and large Renaissance frescoes were committed to a naturalistic aesthetic, which, although allegorical, it was not fantastic, the wonderful elements of Bosch would not be entirely strange to the imagination of the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

The popular imagination was full of fantastic and monstrous images, and certainly Bosch would be nourished by that imagery through iconographic treatises, engravings, literature, etc. Many of the fantastic images would come from couplets, popular sayings, and parables. Then... In what would the originality or importance of Bosch lie and, in particular, of the triptych? The Garden of Earthly Delights?

According to experts, the novel contribution of El Bosco in Flemish Renaissance painting would be to have elevated the iconography fantastic, typical of the minor arts, to the importance of oil painting on panel, normally reserved for the liturgy or devotion pious.

However, the author's imagination plays a leading role, not only when spinning those images fantastic in a satirical and moralizing way at the same time, but for having gone beyond imagined. Indeed, El Bosco lays the foundations for creative elements that can be considered, in a certain way, surreal.

See also Surrealism: characteristics and main authors.

Therefore, while framing himself in tradition, El Bosco also transcends it to create a unique style. His impact was such that he exerted an important influence on future painters such as Pieter Bruegel the Elder.

The composition: tradition and particularity

This piece by the painter would also break with the Renaissance principle that focuses the attention of the gaze on a leading point in the scene.

In the triptych, the scenes certainly respect a central vanishing point, which makes each of the parts converge around a plastically balanced axis. However, although the spatial organization based on verticals and horizontals is evident, the hierarchy of the different elements represented is not clear.

Along with this, we observe the rarity of geometric shapes. Most especially, we note the construction of multiple concatenated but autonomous scenes at the same time that, in terms of the panels of the earthly world and of hell, form a choral environment of placid and suffering roar respectively.

In the central panel, each of these scenes is made up of a group of people who live their own universe, their own world. They carry on a conversation with each other, although a few figures eventually look at the audience. Do you want to integrate it into the conversation?

Purpose and function of the triptych: a conversation piece?

When the V centenary of the triptych was celebrated, the Prado Museum held an exhibition with the collaboration of Reindert Falkenburg, an expert in the field.

Falkenburg took the opportunity to present his thesis on the triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights. For him, this triptych is a conversation piece. According to the researcher's interpretation, this work was not conceived for a liturgical or devotional function, although it certainly alludes to the imaginary of the afterworld (heaven and hell).

On the contrary, this piece was destined for its exhibition in court, for which Falkenburg maintains that its purpose was generate conversation among the visitors, the same ones who might have a life very similar to the one denounced by the painter.

We must remember that the conventional triptychs were destined for the altars of the churches. There they remained closed until there was a solemnity. In the context of the liturgy, the conversation is not, then, a purpose. On the contrary, the contemplation of the images would be destined to the education in the faith and the personal prayer and devotion.

Would this use make sense in court? Falkenburg thinks not. The exhibition of this triptych in a court room could not but have as its purpose the conversation, before the wonderful effect that arises when the outer panels are opened.

Falkenburg argues that the piece also has a specular character, since the characters within the representation practice the same action of the spectators: to converse with each other. The piece, therefore, aims to be a reflection of what happens in the social environment.

The purpose of the painter

All this thus supposes one more originality of the Flemish painter: to give the triptych format a social function, even within his deep Catholic moral sense. This also responds to the training of El Bosco and the conditions of his commission. Bosco was an elite painter, who can be considered conservative despite his lush imagination. He was also an educated, well-informed and documented man, accustomed to reading.

As a member of the brotherhood of Our Lady, and under the influence of the spirituality of the Brothers of Common Life (The imitation of Christ, Thomas of Kempis), Bosco managed to explore Catholic morality in depth and, like a prophet, wanted to give signals about human contradictions and the fate of sinners.

His morality is neither accommodative nor soft. Bosco looks hard at the environment, and does not skimp on denouncing even ecclesiastical hypocrisy when necessary. For this reason, the Jerónimo Fray José de Sigüenza, responsible for the Escorial collection at the end of the century XVI, affirmed that the valuable thing of the Bosco in front of the contemporary painters was that this achieved paint the man inside, while the others barely painted his appearances.

About Bosco

Bosco's real name is Jheronimus van Aken, also known as Jheronimus Boch or Hieronymus Boch. He was born around 1450 in the city of Hertogenbosch or Bois-le-Duc (Bolduque), duchy of Bravante (now the Netherlands). He was raised in a family of painters and became a representative of Flemish Renaissance painting.

There is very little information about this painter, as he signed very few paintings and did not date any of them. Much of his works have been attributed to the author after serious research. It is known, yes, that Felipe II was a great collector of his paintings and that he, in fact, commissioned the piece from him The final judgement.

Bosco belonged to the brotherhood of Our Lady of Hertogenbosch. It is not surprising that he is interested in the themes of Catholic morality, such as sin, the transitory nature of life and the madness of man.

Order and destination of The Garden of Earthly Delights: from the Nassau house to the Prado Museum

Engelberto II and his nephew Henry III of Nassau, German noble family that owned the famous Nassau castle, were members of the same brotherhood as the painter. It is presumed that one of them was responsible for commissioning the piece from the painter, but it is difficult to determine because the exact date of its creation is unknown.

It is known that the piece already existed by the year 1517, when the first comments on it appeared. By then Henry III had the triptych under his power. He inherited it from his son Enrique de Chalons, who at the same time inherited it from his nephew Guillermo de Orange, in 1544.

The triptych was confiscated by the Spanish in 1568, and was owned by Fernando de Toledo, prior of the order of San Juan, who kept it until his death in 1591. Felipe II acquired it at auction and took it to the El Escorial monastery. He himself would call the triptych The strawberry tree painting.

In the 18th century the piece was cataloged with the name of The creation of the world. Towards the end of the 19th century, Vicente Poleró would call it Painting of carnal pleasures. From there the use of expressions became popular Of earthly delights and finally, The Garden of Earthly Delights.

The triptych remained in El Escorial from the end of the 16th century until the advent of war Spanish civilian, when it was transferred to the Prado Museum in 1939, where it remains until the date.

Other works by El Bosco

Among his most important works the following can be noted:

- Saint Jerome in prayer, around 1485-1495. Ghent, Museum voor Schone Kunsten.

- The temptation of San Antonio (fragment), around 1500-1510. Kansas City, The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.

- Triptych of the Temptations of Saint Anthony, around 1500-1510. Lisbon, National Museum of Ancient Art

- Saint John the Baptist in meditation, around 1490-1495. Madrid, Lázaro Galdiano Foundation.

- St. John on Patmos (obverse) e Passion Stories (reverse), around 1490-1495. Berlin, Staatliche Museen

- The Adoration of the Magi, around 1490-1500. Madrid, Prado Museum

- Ecce homo, 1475-1485. Frankfurt am Main, Städel Museum

- Christ carrying the cross (obverse), Christ child (reverse), around 1490-1510. Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum

- Triptych of the Last Judgment, around 1495-1505. Bruges, Groeningemuseum

- The Hay Wagon, around 1510-1516. Madrid, Prado Museum

- Extraction of the stone of madness, around 1500-1520. Madrid, Prado Museum. Authorship in question.

- Table of deadly sins, around 1510-1520. Madrid, Prado Museum. Authorship in question.

Conversations about The Garden of Earthly Delights in the Prado Museum

The Prado Museum has made available to us a series of audiovisual materials to better understand the triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights. If you like to challenge the way of interpreting works of art, you cannot miss this conversation between a scientist and an expert in art history. It will surprise you: