Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: the best 5 poems of her analyzed and explained

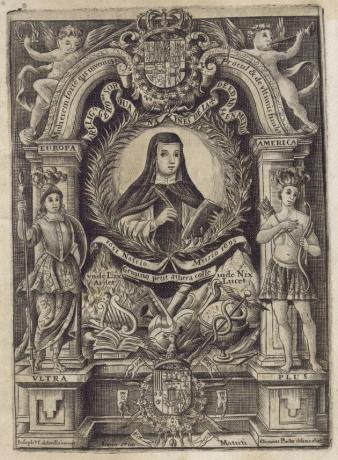

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (1651-1695) was a Mexican nun and writer. She is the author of a baroque literature of the highest invoice, which gave her prestige and recognition in both New Spain and Spanish high society. She is considered one of the greatest exponents of the Spanish golden age.

Octavio Paz says that in colonial times, the court and the cloister parlor were the only spaces in which a woman could intellectually rub shoulders with men. And Sor Juana, who avoided marriage to be able to dedicate herself to letters, she knew how to take advantage of those spaces very well.

Her work encompasses a diversity of literary genres, among which the theater, the auto sacramental and the lyric stand out. Within the context of her lyrical work, Sor Juana wrote sonnets, redondillas, décimas, romances, and many other literary forms.

But not because she was a nun, Sor Juana dedicated herself only to Christian themes. On the contrary, a good part of her work also talks about love, values, women, the classical world and virtue, among others.

In this article you will find a selection of some of her most emblematic poems, whose formal characteristics and topics addressed continue to fascinate us.

That she consoles a jealous person by epilogue the love series

The sonnet is made up of fourteen verses of major art in consonant rhyme, almost always hendecasyllables, grouped into two quartets and two triplets.

In this sonnet, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz exposes the fate of love when the jealous, mobilized by the passions that possess it from the beginning, lets itself be carried away. The jealousy that she had for fear of losing her loved one, becomes the cause of losing her.

Love begins with restlessness,

solicitude, ardors and sleeplessness;

it grows with risks, challenges and misgivings;

hold on to crying and begging.

Teach him lukewarmness and detach

preserve being between deceptive veils,

until with grievances or jealousy

with her tears she extinguishes her fire.

The beginning of it, the middle and end of it is this:

So why, Alcino, do you feel the detour

of Celia, what other time did you love well?

What reason is there that pain costs you?

Well, she didn't cheat on you my love, my Alcino,

but the precise term arrived.

Complain about luck: she hints at her aversion to vices and justifies her amusement to the Muses

In this sonnet, the lyrical voice confronts the order of the world, with its vanities and vices. Faced with these temptations, for the poet there is no possible dilemma: what would money and beauty be worth without understanding?

In chasing me, world, what are you interested in?

How do I offend you, when I just try

put beauties in my understanding

and not my understanding in the beauties?

I do not value treasures or riches,

and so it always makes me happier

put riches in my understanding

than my understanding in riches.

I do not estimate beauty that has expired

It is civil spoil of the ages

nor do I like wealth fementida,

taking for the best in my truths

consume vanities of life

than to consume life in vanities.

Contains a fantasy content with loving decent

The dream of love is present in this sonnet. But we must not only read love here as a human relationship, but also as a divine experience. Divine love cannot be possessed, but it can be experienced. The lyrical voice yearns and enjoys at the same time.

Stop, shadow of my elusive good

image of the spell that I love the most,

beautiful illusion for whom I happily die,

sweet fiction for whom I live.

If the magnet of your attractive thanks

serve my chest of obedient steel,

Why do you make me fall in love, flattering,

if you have to mock me then runaway?

More emblazon can not satisfied

that your tyranny triumphs over me;

that although you leave the narrow bond mocked

that your fantastic form belted,

it does not matter to mock arms and chest

if my fantasy carves you prison.

See also Analysis of the poem Stop shadow of my elusive good by Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.

Foolish men you accuse

The famous poem "Foolish men who accuse ..." is a round, that is, a poem by stanzas of four verses of minor art with consonant rhyme of the first with the last, and the second with the third. In this one in particular, Sor Juana criticizes the position of men towards women.

Foolish men you accuse

to the woman without reason,

without seeing that you are the occasion

of the same thing that you blame:

yes with unequaled eagerness

you request their disdain,

Why do you want them to do well

if you incite it to evil?

You fight their resistance

and then, with gravity,

you say that she was lightness

what the stagecoach did.

To seem wants the boldness

of your looking crazy

the boy who puts the coconut

and then he is afraid of her.

You want, with foolish presumption,

find the one you are looking for,

for pretended, Thais,

and in possession, Lucrecia.

What humor can be weirder

than the one who, lacking advice,

he himself blurs the mirror,

and he feels that it is not clear?

With favor and disdain

you have the same condition,

complaining, if they treat you badly,

making fun of you, if they love you well.

You are always so foolish

that, with unequal level,

you blame one for cruel

and another for easy blame.

Well, how can she be tempered

the one that your love pretends,

if the one who is ungrateful, offends,

and the one that is easy, angry?

But, between anger and grief

that your taste refers,

well there is the one who does not love you

and complain at good time.

Give your lovers sorrows

to your freedoms wings,

and after making them bad

you want to find them very good.

What greater fault has he had

in a wrong passion:

the one that falls by request,

or the one who begs to be fallen?

Or what is more to blame,

even if anyone does wrong:

the one who sins for the pay,

or the one who pays to sin?

Well, why are you scared

of the fault that you have?

Want them which you do

or make them which you are looking for.

Stop requesting,

and later, with more reason,

you will accuse the fans

of which I will beg you.

Well with many weapons I found

what your arrogance deals with,

Well, in promise and instance

you put together the devil, the flesh and the world.

See also Analysis of the Poem Foolish men you accuse by Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.

To Christ in the Sacrament, day of communion

We speak of lyrical romance to refer to an indefinite series of verses, almost always eight syllables. These verses have an assonance rhyme in pairs, while the odd ones are independent.

In this romance, once again divine love is present, this time in Christ, materialized in the Eucharist. The presence of the living God in the Eucharist is thus the presence of love that completes, dignifies and justifies existence.

Sweet lover of the soul,

sovereign good to which I aspire,

you who know the offenses

punish profits;

divine magnet in which I adore:

today how auspicious I look at you,

that you spoil me the audacity

to be able to call you mine:

today that in loving union

it seemed to your love

that if you weren't in me

it was not enough to be with me;

today what to examine

the affection with which I serve you

to the heart in person

you have entered yourself,

I ask: is it love or jealousy

such careful scrutiny?

That who registers everything

gives suspect signs.

But alas, ignorant barbarian,

and what mistakes have I said,

as if the human encumbrance

hinder the divine lynx!

To see the hearts

it is not necessary to assist them,

that for you are patents

the bowels of the abyss.

With an intuition present

you have in your registry

the past infinity

up to the finite present.

Then you did not need

to see my chest,

if you are looking at it wise,

enter to look at it fine.

Then it's love, not jealousy,

what I see in you.

About Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

She was born in the year 1648 and died in 1695. Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz is the name that the writer assumed after her religious profession. Her first name is Juana de Arbaje y Ramírez.

He learned to read from the age of 3 and from the age of 8 he would take Latin classes, a language that he learned quickly.

She was a passionate reader and student, who constantly challenged herself. In 1664 she became a lady-in-waiting for Leonor María Carreto, which allowed her to enter the court.

In that environment, she stood out for the deep knowledge she had of her. In order to continue her apprenticeship, Sor Juana joined the order of the jerónimas, the only worthy way to evade marriage but to find a solution to her economic destiny.

There she dedicated herself to studying and writing, but she also worked as an accountant and archivist. In addition, she wrote on request for many people.

She wrote an abundant literature, but she found an end to her career when a letter written against a sermon by the Portuguese priest Antonio Vieyra brought her great controversy. As a consequence, Sor Juana was forced to leave her studies.

She may interest you: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: biography, works and contributions of the New Spain writer.

Works by Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz

In addition to the lyrical work already mentioned in the text, among the most outstanding works of it the following can be mentioned:

Dramatic

- The efforts of a house.

- The great comedy of the second Celestina, in collaboration with Agustín de Salazar y Torres.

- Love is more labyrinth, in collaboration with Juan de Guevara.

Sacramental cars

- The divine Narcissus.

- The martyr of the sacrament.

- The scepter of Joseph.

Miscellaneous

- Praise to the Blessed Sacrament.

- Allegorical Neptune.

- Castálida Flood.

- Athenagoric Letter.

- Reply to Sr. Filotea de la Cruz.