What relationship do Romanticism and Nationalism have?

is quite well known the relationship that exists between Romanticism and nationalism. In fact, they are so linked that it is difficult to establish which of the two represents the starting point of the other. Does nationalism exist because it drank from the seed established by the romantic movement, or rather did the romantic movement exist as an evolution of an incipient nationalism?

To clarify the issue, it is necessary to take a journey through history. Only in this way will we be able to see more precisely what relationship they have with each other, what their origins were and where both movements derived with the passing of time.

- Related article: "The 15 branches of History: what they are and what they study"

What is the relationship between Romanticism and Nationalism?

It may seem like an exaggerated statement, but if we stick to the light of history, we will realize that it is not so much. Because, while in the France of the first decades of the 18th century the Enlightenment triumphed, which radiated its knowledge throughout Europe within the framework of the well-known

Century of the lights, A radically different movement was brewing in the German territories, which would implant the seed of the following romantic and nationalist currents.. We are talking about the Sturm und Drang, "storm and momentum" in German.The origin of the name of this movement is in the homonymous play by Friedrich Maximilian Klinger (1767-1785), premiered in 1776. He Sturm und Drang He reacted directly against the rationalism imposed by enlightened society and advocated the exaltation of subjectivism and freedom in artistic expression. In other words, it was a genuine protest against the Academy and its rigid rules; For the first time, a philosophical-artistic movement defended the importance of the free and personal creation of the artist.

- You may be interested in: "Since when does Nationalism exist?"

He Sturm und Drang and the roots of Romanticism

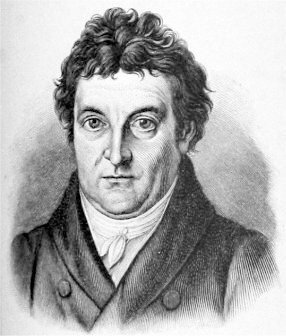

To give us an idea of the influence that the Sturm und Drang in the appearance of nationalist movements, let's just say that Johann Gottfried Herder (1744-1803), one of the founders of German nationalism, encouraged this pre-romantic movement, while defending individual freedom, so closely linked to popular sovereignty and the autonomy of peoples.

For his part, the poet Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832), who by the way knew Herder personally, materialized the ideas of the Sturm und Drang in his literary works, especially in The misadventures of young Werther, published in 1774, as well as in his poem Prometheus, finished that same year. In the first, the emotions and the subjective world of the protagonist are praised to extreme levels and, in the second, the author makes a true apotheosis of the romantic artist who rebels against authority in the figure of Prometheus, the classical hero who defies the Almighty Zeus.

On the other hand, Johann Gottlieb Fichte (1762-1814), philosopher disciple of Kant, stimulated in his works the term coined by Herder, the volksgeist, used to refer to the condition of being of a town, to his spirit. We must look for the origins of this idea in the German resistance against the Napoleonic invasions, a true European leitmotiv that paid considerably the nationalist terrain, since, in their fight against French imperialism, the invaded peoples began to become aware of their National reality.

- Related article: "What is Cultural Psychology?"

The invention of the national past

However, does this national reality defended by the German pre-romantics really exist? The theories of Fichte and Herder were in open contradiction with the Enlightenment precepts, which were much more global and tended towards a more universal vision of humanity. For the flag bearers of Sturm an Drang, a nation had immutable characteristics since ancient times, almost legendary times that had forged its identity and its spirit (the famous volksgeist).

For it, pre-romantics and later romantics do not hesitate to misrepresent the past and take from history those elements that are useful for their objective. In this sense, the Middle Ages play a prominent role, while these authors see in this period the roots of the german homeland. It is then when popular folklore acquires great importance, which authors such as the Grimm brothers are going to capture in writing as a way of vindicating this ideal origin of the Germanic peoples. In this way, the foundations of national invention are laid, that is, the adaptation of history to the interests of the nation.

And the rest of Europe?

Although, as we have already seen, the German territories played a huge role in the rise of the first Romanticism and, therefore, of nationalism, it would be wrong to believe that the rest of the European countries did not experience a similar experience. In fact, and as we have also commented, the Napoleonic wars had a lot to do with the unstoppable advance of nationalism in Europe.

In Spain, for example, the incipient Romanticism appeared at that time. Authors such as Francisco de Goya (1746-1828), with his whims and, above all, with his black paints, are clearly laying the foundations for the future romantic movement, although Goya's case is not an example of nationalism, since his vision is much broader and more cosmopolitan.

In Russia, the French invasion is a clear precedent for later nationalism; We have a very obvious example in one of the symbolic works of Russian literature, the War and peace by Lev Tolstoy (1828-1910) which, later, during the Soviet era, will rise as an unparalleled patriotic monument.

The consequences of the Napoleonic invasions, as well as the subsequent Congress of Vienna (1814), which sought to restore order of the Old Regime in Europe, reached the first decades of the 19th century, when the romantic movement was in full swing. apogee. All of this is the cause, for example, of the Belgian nationalist movement, a buffer state that had been created by the Restoration to stop any other revolutionary impulse coming from France. In 1830, the disagreements between this new territory and the country to which it was subjected, the Netherlands (caused by religious and language differences) made Belgium become independent and begin its journey as a country independent.

The ripple effect of romantic nationalism

The case of Belgium was not isolated. The nationalist ideas that arose within romantic subjectivism and its exaltation of the individual as the only person responsible for himself, penetrated deeply into the different towns in which he was divided Europe. The romantic idea of individual freedom it matched perfectly with the right of peoples to self-govern and to form states based on their national characteristics.

Belgium became independent in 1830, but a few years earlier Greece had done the same, freed from the yoke of the Ottoman Empire. And to understand the great importance that the intelligentsia attached to nationalism, we can use the example of Lord Byron (1788-1824), English poet who went to Greece to fight for its independence (and who, by the way, died of malaria before entering combat). On the other hand, Eugène Delacroix (1798-1863), the French romantic painter, made a canvas about the massacre that the Ottomans had perpetrated on the island of Chios, a clear denunciation of the subjugation of the towns. The canvas, executed in 1824 (two years after the event), was certainly harshly criticized. Romantic rebellion in its purest state.

The revolutionary wave that had started with the French Revolution could no longer be stopped. The Congress of Vienna and the restoration of the old pre-Napoleonic European order were a complete failure. In 1820, Spain was at the forefront of the rebellion with the uprising of Rafael del Riego in Cabezas de San Juan., Seville, with the aim of restoring the Constitution of 1812. Ten years later, in 1830, the Three (journeys) glorious, three days of street fighting and barricades that result in the overthrow of the autocratic king Carlos X (brother of the guillotined king) and his replacement by the more constitutional Luis Felipe de Orleans.

In 1848, during the call spring of nations, the nationalist fever was already a fact. It was the time of the independence claims of the northern Italian territories, who wanted to free themselves from Austrian power, and it was also the time of the Risorgimento Italian and the German unification movement. While, In Spain, in the mid-19th century, Spanish nationalism came to life through numerous historical misrepresentations, such as the famous Reconquest and the myth of Pelayo, the Asturian caudillo, and in Catalonia the Renaissance and the fabrication of Catalan founding myths. All in line with the romantic ideas of Herder, Fichte and Hegel and their volksgeist, he spirit of the people.