César Vallejo: 8 great poems analyzed and interpreted

César Vallejo (1892-1938) is one of the greatest exponents of twentieth-century Latin American avant-garde poetry. His literary contributions revolutionized the way of writing and his influence has reverberated throughout the world. He is also one of the most important Peruvian poets, if not the most important.

In the words of Américo Ferrari, as an exponent of the avant-garde:

(...) it is perhaps Vallejo who embodies the freedom of poetic language in the most complete way: without recipes, without preconceived ideas about what poetry should be, dives between anguish and hope (...), and the fruit of that search is a new language, an accent unheard.

This selection of poems, which we are going to analyze and interpret, exemplifies the originality and diversity in the range of tones that characterize the poet. Some mix drama with humor. They all point to the themes and obsessions of his poetics: death, temporality, transcendence, everyday life, brotherhood, solidarity, compassion, opposites, destiny, pain, illness, etc.

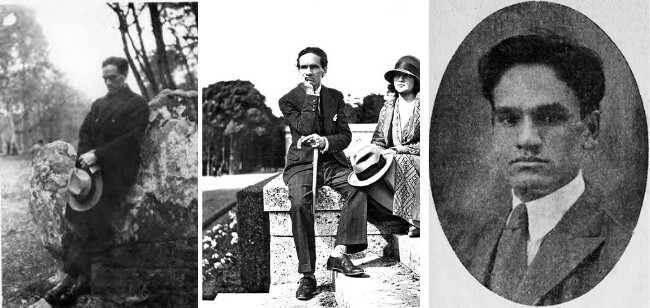

Photograph of César Vallejo in Nice, 1929.

1. Considering cold, impartially ...

Considering coldly, impartially,

that man is sad, he coughs and yet

she delights in his red chest;

that all he does is compose himself

of days;

that he is a gloomy mammal and combs his hair ...Considering

that man proceeds smoothly from work

and he reverberates boss, he sounds subordinate;

that the time diagram

is constant diorama on his medals

and, half open, his eyes studied,

from distant times,

his starving dough formula ...Effortlessly understanding

that man stays, sometimes, thinking,

like wanting to cry,

and, subject to tending itself as an object,

he becomes a good carpenter, sweats, kills

and then sings, has lunch, buttons ...Considering also

that man is truly an animal

And yet, turning around, he hits me with his sadness on the head ...Examining, in short,

The found pieces of him, the toilet of him,

his despair, ending his atrocious day, erasing it ...Understanding

that he knows that I love him,

that I hate him with affection and he is, in short, indifferent to me ...Considering your general documents

and looking with glasses that certificate

which proves that he was born very small ...I make a sign,

comes,

and I give him a hug, excited.

What difference does it make! Excited… Excited…

The poem builds the image of the human being in all its aspects by listing characteristics presented with an objective, scientific and distant tone.

It emphasizes its perishable and limited being, annihilated by routine and hierarchical orders, lost in the masses. But also his capacity for depth and introspection: his emptiness and sadness, the hunger for knowledge.

It contrasts the lower aspects, such as its animal characteristics and "its toilet", aspects associated with shame that we would like to hide and deny, with the successes and achievements of history: the medals, the advances scientists.

Thus, a tribute to the human being is made, it celebrates his capacity for resilience and suggests reconciliation and acceptance with his shortcomings and faults. It welcomes the human being as he is, with an emotionality that contrasts and ends up winning the victory over the rational and scientific tone of the poem.

It suggests that feelings of brotherhood and compassion have the last word and ultimately prevail over everything else.

2. It comes to me, there are days, a tremendous desire, politics ...

It comes to me, there are days, a wild, political win,

to love, to kiss the affection on both of his faces,

and a love comes from afar

demonstrative, another wanting to love, of degree or force,

the one who hates me, the one who tears his paper, the little boy,

to whom he cries for whom he cried,

the king of wine, the slave of water,

to the one who hid himself in his wrath,

the one who sweats, the one who passes, the one who shakes his person in my soul.

And I want, therefore, to accommodate

to the one who speaks to me, his braid; his hair, to the soldier;

his light, to the great one; the greatness of him, the boy.

I want to iron directly

a handkerchief that cannot cry

and when I'm sad or happiness hurts,

mending children and geniuses.I want to help the good to be his little bit of bad

and he urges me to be seated

to the right hand of the left-hander, and answer the dumb,

trying to be useful to you in

what I can, and I also want very much

wash the lame foot,

and help the next one-eyed man to sleep.Ah love, this one, mine, this one, the world cup,

interhuman and parochial, project!

He comes to me bareback,

from the ground up, from the public groin,

and, coming from afar, it makes you want to kiss him

the scarf to the singer,

and to the one who suffers, kiss him in his frying pan,

to the deaf, in his cranial murmur, undaunted;

to the one who gives me what I forgot in my bosom,

on his Dante, on his Chaplin, on his shoulders.I want, to finish,

when I'm on the famous brink of violence

or full of chest my heart, I would like

help the one who smiles laugh,

to put a bird on the evil one in the neck,

take care of the sick by angering them,

buy from the seller,

help him kill the matador — terrible thing—

and I would like to be good to me

throughout.

The poem puts a humorous twist on one of the great themes of Vallejo's poetics: brotherhood, companionship, and compassion. Through the resource of caricature and with a mischievous tone, a need, vocation or call to express emotion and affection is responded to.

We find the enumeration dictated by free association and the resource of oxymoron. The game of putting together opposing elements gives the feeling of a failed complement: "a handkerchief that cannot cry."

We can also see the influence of cubism that develops the vision of man fragmented and composed of the parts of him.

Part of the richness of the poem is given by the convergence of dissimilar objects that has the ability to evoke multiple sensations, emotions, memories and associations in the reader.

3. The old asses think

Now i would dress

of a musician to see him,

I would collide with his soul, rubbing fate with my hand,

it would leave him alone, since he is a soul on pauses,

anyway, he would let her

possibly dead on his dead body.

He could stretch out in this cold today,

he could cough; I saw him yawn, doubling in my ear

his fateful muscle movement.

So I mean a man, his positive plate

and why not? to the boldo performer of him,

that horrible luxurious filament;

to his cane with a silver fist with a little dog,

and the children

who he said were his funeral brothers-in-law.

That is why I would dress as a musician today,

I would collide with the soul of him who stared at my matter ...

But I will never see him shaving at the foot of his morning;

no longer, no longer, no longer for what!

Must see! What a thing!

What ever ever his ever!

It refers to the fond memory of "a man" who has died. The man can be anyone and refers to a generic man.

We find the longing that takes the form of the loving gestures and gifts he wanted to give her, or in imagining what this man would do if he were present now.

In this case, “I would dress as a musician” is a completely original way of referring, perhaps, to a serenade, a favorite song and with a touch of humor, we can associate it with those who appear dressed up at children's birthday parties: as a clown, magician, spider-man, princess Elsa or “de musician".

The weight of the presence of the man in the poem appears embodied in his garments and in the most important acts. routine and everyday: "his cane with a silver fist with a puppy" and in "seeing him shaving at the foot of the morning".

Implicitly there is a question about the existence and transcendence of man, since his time is ephemeral and This man who is anyone and at the same time is unique in his individuality, will disappear: Never!".

4. Today I like life much less ...

Today I like life much less,

but I always like to live: I already said it.

I almost touched the part of my whole and held back

with a shot in the tongue behind my word.

Today I feel my retreating chin

and in these momentary pants I say to myself:

So much life and never!

So many years and always my weeks ...

My parents buried with their stone

and his sad stretch that has not ended;

full body brothers, my brothers,

and, finally, my being standing and in vest.

I like life enormously

but of course

with my dear death and my coffee

and seeing the leafy chestnut trees of Paris

and saying:

This is an eye; a forehead this one, that one... And repeating:

So much life and the tune never fails me!

So many years and always, always, always!

I said vest, I said

everything, part, craving, he says almost, not to cry.

That it is true that I suffered in that hospital that is next door

and that it is right and wrong to have looked

from the bottom up my organism.

I would like to live always, even if it were on the belly,

because, as I was saying and I repeat it,

So much life and never and never! And so many years

and always, always a lot, always always!

With an optimistic vision, the poem shows an appreciation and a taste for life, even from the perspective of illness and death. Thus appears the stay in the hospital, and the feeling of mourning for the death of their loved ones appears as a constant companion of life itself.

The reflection on time, the interpellation of the reader as a brother and the vision of the fragmented man, can also be appreciated in the poem.

5. It is where I put myself ...

It is that the place where I put myself

the pants, is a house where

I take off my shirt loudly

and where I have a soil, a soul, a map of my Spain.

Right now he was talking

of me with me, and put

on a small book a tremendous bread

and then I have made the transfer, I have transferred,

wanting to hum a little, the side

right of life to the left side;

later, I have washed everything, my belly,

spirited, worthily;

I have turned to see what gets dirty,

I have scraped what brings me so close

and I have ordered the map well that

nodding or crying, I don't know.

My house, unfortunately, is a house,

a ground by chance, where he lives

with your inscription my beloved spoon,

my dear skeleton no longer letters,

the razor, a permanent cigar.

Really, when I think

in what life is,

I can't help but tell Georgette

in order to eat something nice and go out,

in the afternoon, buy a good newspaper,

save a day for when there isn't,

one night too, for when there is

(That's what they say in Peru — I excuse myself);

in the same way, I suffer with great care,

so as not to scream or cry, as the eyes

they possess, independently of one, their poverties,

I mean, his trade, something

that slips from the soul and falls to the soul.

Having traversed

fifteen years; after fifteen, and before fifteen,

one actually feels silly,

it is natural, otherwise what to do!

And what to stop doing, which is the worst?

But to live, but to arrive

to be what is one in millions

of breads, among thousands of wines, among hundreds of mouths,

between the sun and its moonbeam

and between the mass, the bread, the wine and my soul.

Today is Sunday and, therefore,

The idea comes to mind, to the chest the crying

and to the throat, as well as a large lump.

Today is Sunday, and this

it has many centuries; otherwise,

It would be, perhaps, Monday, and the idea would come to my heart,

to the brain, the crying

and to the throat, a dreadful desire to drown

what I feel now,

as a man that I am and that I have suffered.

The poem has an introspection tone and reflects on being in the present and the place he inhabits, both physically and with his thought: “a house” and “a map of my Spain”.

Human existence is shown in the most everyday and routine acts and objects. Acts like washing what gets dirty or "going out to eat something." The objects are generally small and yet, full of familiarity with personal and distinctive touches: "a little book", "a tremendous bread", "with its inscription my beloved spoon".

The present with its daily life is put into perspective in light of what it means to carry history and memories; the passage of 15 years is mentioned, which may refer to the life of the individual, but also evokes something that "has been going on for many centuries", alluding to the history of humanity.

Throughout the poem the reflection on the expression and what to do poetic appears implicit: in the “loud voice”, in the “humming” and “in the care not to scream or cry”. In this case, what you want to express is something stuck and accumulated that is linked to the reflection on the transcendence of the individual.

6. This...

This

it happened between two eyelids; I trembled

in my sheath, angry, alkaline,

standing next to the lubricious equinox,

At the foot of the cold fire that I ended up in

Alkaline slip, I'm saying,

more here of the garlic, on the syrup meaning,

deeper, much deeper, of the rust,

as the water goes and the wave returns.

Alkaline slip

also and greatly, in the colossal montage of the sky.

What spears and harpoons will I throw, if I die

in my sheath; I will give in sacred banana leaves

my five subordinate bones,

and in the look, the look itself!

(They say that sighs are edified

then bony, tactile accordions;

They say that when those who are finished die like this,

Oh! die off the clock, hand

clinging to a lonely shoe)

Understanding it and everything, colonel

and everything, in the crying sense of this voice,

I make myself ache, I draw sadly,

at night, my nails;

then I have nothing and I speak alone,

I check my semesters

and to fill my vertebra, I touch myself.

The poem looks into the deepest part of the human being, the interiority of him and the emotional universe. The images made up of opposing elements seem to be the only ones capable of describing some human emotions.

It reflects on the transcendence of man, one of the concerns of the author's poetics, by means of the surrealist language: "I will give in sacred banana leaves / my five little bones subordinates ". We find images that refer to dreams, loaded with free unconscious associations that do not pretend to be rationalized, but generate all kinds of sensations in the reader.

In this poem, mentions of corporeity create the sense of poverty, loneliness, and desolation of the condition. human: the body, nails, bones and vertebrae are, ultimately, the only companions and witnesses of the existence.

7. Hat, coat, gloves

In front of the French Comedy, there is the Café

of the Regency; in it there is a piece

secluded, with an armchair and a table.

When I enter, the motionless dust has already risen to its feet.

Between my lips made of rubber, the pavesa

From a cigarette it smokes, and in the smoke you see

two intensive smokes, the thorax of the Coffee,

and in the thorax, a deep rust of sadness.

It is important that the autumn be grafted onto the autumns,

it matters that autumn is made up of suckers,

the cloud, of semesters; cheekbones, wrinkle.

It matters to smell crazy, postulating

How warm is the snow, how fleeting is the turtle,

the how how simple, how sudden the when!

Start with a narrative tone. Starring in the poem are the objects, which account for the voice and the narrated place. Starting with the title of the poem: "Hat, coat, gloves" which could be referring to the poet, as well as the cigarette.

In the Café there is a gloomy air of loneliness and abandonment. The passage of time, decay, what ages or enters the process of death, inhabit the place. This is suggested, among others, by the accumulation of dust, rust and autumn as the season when trees lose their foliage and nature prepares for winter.

To study the environment of the place, the image of an X-ray is suggested; the medium that allows it seems to be cigarette smoke, and the object to be analyzed, the Café de la Regencia: “and in the smoke you see / (...) the thorax of the Café, / and in the thorax (.. .) ".

8. The black heralds

There are blows in life, so strong… I don't know!

Blows like the hatred of God; as if before them,

the hangover of everything suffered

it will pool in the soul... I don't know!They are few; but they are... they open dark ditches

on the fiercest face and the strongest back.

Perhaps it will be the foals of the barbarians Attila;

or the black heralds that Death sends us.They are the deep falls of the Christs of the soul

of some adorable faith that Fate blasphemes.

Those bloody hits are the crackles

of some bread that burns on the oven door.And the man… Poor… poor! Roll your eyes like

when a clap calls us over the shoulder;

turns crazy eyes, and everything lived

he puddles, like a pool of guilt, in his eyes.There are blows in life, so strong… I don't know!

It is a lyric poem in which the Alexandrian verse and rhyme predominate. The poem deals with human pain and shows the impossibility of expressing, apprehending or understanding it. Words and language are insufficient and it is necessary to resort to new ways of expressing, in this case through simile.

Read more about Poem The Black Heralds by César Vallejo.

César Vallejo and the avant-garde

For the avant-garde, poetic language had lost its expressive capacity; Classic and romantic forms had been abused, and there was a sense of harassment and weariness in the climate.

In this search, music has a leading role, and the poetry of César Vallejo stands out precisely for this. Rhyme is put aside and free verse and prose prevail. The music follows the intrinsic sound of the language and the door opens at a heterogeneous rhythm, with different accents.

His language is also guided by intuition and free association. The influence of surrealism and expressionism is welcomed. Repetition, grammatical and syntactic transgressions, and dream language create images and senses that escape reason, but that communicate with great efficiency deep emotions and sensations.

Subjects, places and words that were previously excluded from art and poetry are welcomed. For example, it refers to the animal side of the human being with its biological functions. He embraces terms that belong to scientific jargon and the ingenuity of spoken language. We find words without any poetic prestige, such as puddles, toilet, groin, muscular, etc.

Everyday life, routine and common objects are the protagonists in his poetics. Bread, newspaper, pants and other garments are frequent, and among his many merits is added the fact that he has managed to make poetry of the most mundane and ordinary objects.

The result is a poetry that does not pretend to be fully or rationally understood, but that communicates with the reader through conscious and unconscious sensations and emotions that manage to be transmitted through music and intuition.

Biography of César Vallejo

He was born in Santiago de Chuco, Peru, 1892. He entered the Faculty of Letters at the University of Trujillo, but had to leave his career for economic reasons. Years later he resumed his studies paying for them as a teacher. He was the teacher of the renowned novelist Ciro Alegría. He graduated with his thesis Romanticism in Castilian poetry.

After having published some of his poems in newspapers and magazines, in 1918 he published The black heralds. In this same year his mother died and he returned to Trujillo. In 1920 he is accused of starting a fire and is wrongfully imprisoned for almost four months. His imprisonment could be related to the socialist articles that he published denouncing some injustices. While in jail he writes Trilce and he publishes it in 1922.

He travels to Europe in 1923, and there he works as a journalist and translator. He frequents the writers Pablo Neruda, Vicente Huidobro, Juan Larrea and Tristan Tzara. In 1924, his father died, and the poet was hospitalized for an intestinal hemorrhage from which he recovered successfully.

In 1927 he met Georgette Vallejo, when she was 18 years old, and they married in 1934. In 1928, he founded the Socialist Party in Paris. In 1930 he publishes Trilce in Madrid, and he frequents Federico García Lorca, Rafael Alberti, Gerardo Diego and Miguel de Unamuno. When the Spanish civil war broke out in 1936, together with Pablo Neruda, he founded the Ibero-American Committee for the Defense of the Spanish Republic.

In the years from 1931 to 1937, he wrote various dramatic works and short stories, as well as poems that were later collected and published posthumously as Human poems.

He falls ill on March 24 and dies on April 15, a Good Friday in Paris and with "downpour", as he says in his poem "Black stone on white stone":

I will die in Paris with a downpour,

a day of which I already have the memory.

I will die in Paris - and I do not run -

maybe on a Thursday, as it is today in the fall.

(...)

Years later it was learned that he died because the malaria he suffered as a child was reactivated. His remains are found in the Montparnasse cemetery in Paris.

Works by César Vallejo

These are some of the most outstanding works César Vallejo.

Poetry

- The black heralds (1919)

- Trilce (1922)

- List of bones (1936)

- Spain, take this chalice away from me (1937)

- Sermon on barbarism (1937)

- Human poems (1939)

Narrative

- Climb melographed (stories, 1923)

- Wild fable (novel, 1923)

- Towards the kingdom of the Sciris (nouvelle, 1928)

- Tungsten (novel, 1931)

- Man hour (novel, 1931)

Drama

- Lock-out (1930)

- Between the two banks the river runs (1930)

- Colacho Brothers or Presidents of America (1934)

- The tired stone (1937)

Articles and essays

- Russia in 1931: Reflections at the foot of the Kremlin (1932)

- Russia before the second five-year period (1932)