One Hundred Years of Solitude, by García Márquez: Summary and Analysis

One hundred years of loneliness it has become the most emblematic novel of Latin American culture. Written by Gabriel García Márquez, this work was part of what for some is magical realism and for Alejo Carpentier it is "the marvelous real".

In an exhaustive work of imagination, Gabriel García Márquez tells the story of seven generations of the Buendía family, a family condemned to loneliness.

Summary of One hundred years of loneliness

The novel is structured in unnamed chapters. However, to facilitate understanding of the argument, we have arranged and separated the story into four stages that identify, broadly speaking, the most emblematic passages.

I stage: foundation and early years of Macondo

Since Úrsula Iguarán married her cousin José Arcadio Buendía, she has been afraid of fathering a child with a pig's tail as a result of their relationship. Therefore, she temporarily refuses to consummate the marriage. This causes Prudencio Aguilar to mock José Arcadio Buendía who, offended, kills him in a duel to save his honor. Since then, Aguilar's ghost haunts him and José Arcadio decides to leave town.

Inspired by a dream during his journey through the jungle, José Arcadio Buendía decides to stay at that point on the road and found Macondo, a town that grows little by little.

The town frequently receives visits from gypsies. Its leader, Melquíades, always brings artifacts and objects that obsess José Arcadio Buendía.

By then, the young couple has already conceived three children: José Arcadio, Aureliano and Amaranta. In addition, they adopt Rebeca, the daughter of some relatives. Incest is a constant concern in Úrsula, who over the years observes how Receba and her son José Arcadio fall in love and marry.

A Macondo comes the plague of insomnia, which brings with it the plague of forgetfulness. A concoction of Melquiades puts an end to the plague. The success is such that the gypsy stays to live in Macondo, during which time he writes some scrolls that will only be deciphered many years later.

The patriarch, José Arcadio Buendía, meets again the ghost of Aguilar and goes crazy. The family then ties him to a tree in the backyard, where he will die of a heart attack.

II stage: the civil war and Colonel Aureliano Buendía

When the civil war broke out, Aureliano Buendía fought against the conservatives, commanding a group of Macondo soldiers. He appoints his nephew Arcadio as the civil and military chief of the town.

Arcadio had been the fruit of a loving relationship between José Arcado Jr. and Pilar Ternera, who ran a brothel. He was raised in the home of his grandparents on the condition that his origin was hidden from him. He grew up thinking he was the son of the great patriarch. When he is appointed head of Macondo, Arcadio becomes a dictator and tyrannizes the town. He is shot by conservatives.

During his activity as leader of the Liberals, Colonel Aureliano Buendía faced a total of 32 battles, of which he always came out the loser. Tired, the colonel soon understands that armed struggle is meaningless.

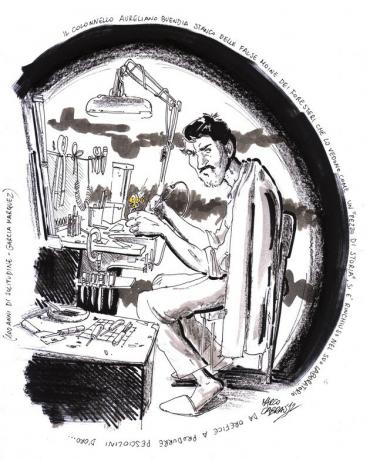

Eventually, Aureliano signs a peace treaty, after which he attempts to commit suicide. He returns to Macondo, where he will spend the rest of his life making and remaking little gold fishes.

III stage: banana fever

Aureliano conceives 17 children of different mothers. One of them, called Aureliano Triste, promotes the train to Macondo, which activates commerce and allows the arrival of inventions such as the telegraph and the cinema. This attracts investment by a foreign group in a banana plantation.

The plantation generates the illusion of prosperity for the town, but a workers' strike will make all this end in a real massacre. The investors, after having exploited the town, retire with their money and Macondo returns to poverty.

From that moment on, the town suffered constant rains for almost five years. Úrsula, the centennial matriarch who has taken care of the whole family, waits for the end of the rains to die and rest her peace.

During the last days of Úrsula, Aureliano (Babylon), the last descendant of the Buendía, was born. Aureliano is the natural son of Meme and Mauricio Babilonia, an apprentice mechanic who is always chased by a swarm of yellow butterflies.

Meme's religious and tyrannical mother, Fernanda del Carpio, opposes the relationship, gets Mauricio out of the way, sends Meme to a convent, takes the child from him and raises him, making him believe that he has been found in a layette.

Stage IV: the end of Macondo

Years go by and little by little the town empties. Aureliano Babilonia, who was characterized by being wise, spends his life deciphering the scrolls that Melquíades had written.

Meanwhile, his aunt Amaranta Úrsula, married to Gastón, returns from Europe. Without knowing of their relationship, both fall in love, Gastón leaves but she becomes pregnant.

During childbirth, in which she dies, she gives birth to a pig-tailed child. Aureliano tries to seek help, but finding only a bartender, he gets drunk and falls asleep. When she wakes up and returns, the child has been eaten by ants.

Finally, Aureliano will be able to decipher Melquíades' scrolls: "because the lineages condemned to one hundred years of solitude did not have a second chance on earth." Then, all of Macondo will be devastated and buried by a hurricane.

Genealogical tree of the Buendía family

Analysis of One hundred years of loneliness

The real wonderful

The novel One hundred years of loneliness It is one of the most representative works of the boom Latin American. Part of what this generation brought in his writing was called by Alejo Carpentier as "the marvelous real", in response to the pretense of calling it "magical realism". Carpentier will say that the real marvelous refers to:

(...) to the gross, latent, omnipresent state in everything Latin America. Here the unusual is everyday, it was always everyday.

The story of this novel relates a series of unusual, unsuspected events, but neither the narrator nor the characters are amazed at these events. In the universe of the narrative, the marvelous behaves as part of everyday reality, as something that does not require explanation. It is, therefore, a literary transgression and who knows if the Cartesian order of thought.

History and myth, memory and oblivion

Each of the events narrated in the novel is related to a reading about historical time, about the construction of memory and the passage of oblivion. The author dialogues with the history and identity of his native Colombia, which is, in some way, an image where Latin America can be recognized.

Macondo is not just a sonorous word: it is an image of a family tree that spreads its branches to shelter all luck of myths, prejudices, anecdotes, values, dreams and wills destined to oblivion, to the transformation of the weather.

The intrahistory of the Buendía family is both a wink to García Márquez's childhood and to History in capital letters.

From a journey through the memory of his native Aracataca, the writer observes the nineteenth-century confrontation between liberals and conservatives, the arrival of the train, the rise of the banana fever, the expansion of capitalism and its practices of domination, in short: the transition from tradition to modernity from the periphery.

García Márquez also dialogues with the values of a culture traversed by all sorts of mythical and religious stories, which have great significant power. He gives voice to the prejudices, the most alive and strong superstitions, and the biblical images of Catholicism, naturalized in the Latin American popular imaginary: an original sin awaiting its punishment, an assumption and a flood are just some of these symbols.

Thus, García Márquez is articulating a mythical discourse, a story of symbols that explains the origin and end of a microcosm in which an image of the world is constructed, and at the same time it is spun in the web of a historical time large.

Characters and archetypes

The names of the characters in this novel are repeated from generation to generation, practically identical, as if it were human archetypes, imbued, as these tend to be, in the deepest conflicts of the culture. They seem to act as mythical characters that represent concepts and thought structures that explain the human thing, like Greek characters.

But García Márquez goes a step further when he gives similar names to each character. With this fact, he emphasizes the weight of inheritance, memory, the mandate of the ancestors, the weight of history and culture.

Perhaps, in some way, each character is not an archetype of individual, but the expression of the various forces in history that push in different directions.

The impulsive and dreamy Arcadios, the withdrawn and curious Aurelians, the energetic but superstitious Úrsulas or an extremely Fernanda religious and tyrannical, can represent, after all, the forces of history struggling to predominate (the search for knowledge, military force, religion, prejudice, capitalism), images of the world refused to disappear, all woven into the great story of the founder.

Love and history

But what can these forces, these images, do against the passage of time? What can they possibly against nature? What can they do against the mystery of symbols and imagination? What can they against human destiny?

In each account of One hundred years of loneliness, in the history of each character and in the way in which each one is spun, only one force remains tied, veiled, cornered by the energy of the opposing forces: the love, that every time it peeks out, it struggles unsuccessfully to break through. This vital human force succumbs to the weight of a culture that, in a sense, condemns the Buendías to live one hundred years of solitude.

See also:

- Gabriel García Márquez: biography and books.

- The Labyrinth of Solitude by Octavio Paz.

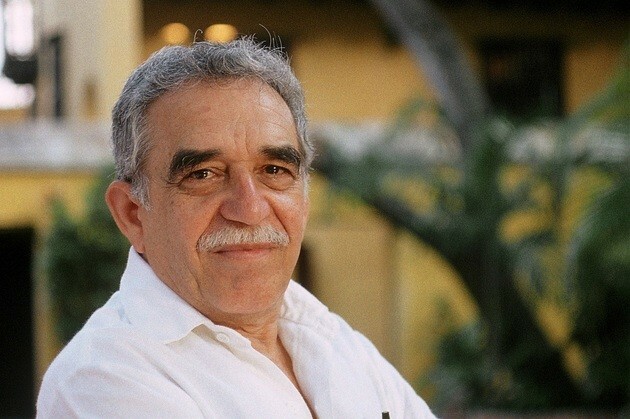

Biography of Gabriel García Márquez

Gabriel García Márquez was born on March 6, 1927 in Colombia, specifically in the Aracataca town. Because his parents went in search of better economic opportunities to Sucre, Gabo was raised by his his grandparents and aunts, from whom he heard many stories that inspired much of his literature, especially the novel One hundred years of loneliness.

He attends the National University in Bogotá, but due to its closure after the Bogotazo of 1948, García Márquez moved to Cartagena to continue his studies. He never graduates, but joins the Barranquilla Group, in which important figures of the Colombian cultural scene such as José Félix Fuenmayor and Ramón Vinyes, the latter of origin Catalan.

That same year, the writer began his career as a columnist, and over time worked for newspapers The universal Y The Herald of Barranquilla, The viewer and for the magazine Myth.

He lived abroad for some years, interspersing short stays between countries such as France, Poland, Hungary, the Democratic Republic Germany, Czechoslovakia, the Soviet Union, Venezuela, Cuba and the United States, where Columbia University awarded him an honorary doctorate Cause. Finally, he resided in Mexico for many years and there he worked as a film scriptwriter and director of publications. The family Y Events.

Publish your masterpiece One hundred years of loneliness in 1967, at the height of the boom Latin American. This work would very quickly become an unsuspected publishing success. Finally, he won the Nobel Prize for literature in 1982, for which he wrote a speech called "The loneliness of Latin America."

Gabriel García Márquez passed away in Mexico City on April 7, 2014.

Most important works of Gabriel García Márquez

Among some of the most important titles of him, we can mention the following:

- 1955.- Litter

- 1961.- The colonel has no one to write to him

- 1962.- The bad time

- 1967.- One hundred years of solitude

- 1970.- Story of a castaway

- 1972.- The incredible and sad story of the candid Eréndira and her heartless grandmother

- 1975.- The Autumn of the Patriarch

- 1981.- A Chronicle of a Death Foretold

- 1985.- Love in times of cholera

- 1989.- The general in his labyrinth

- 1992.- Twelve pilgrim tales

- 1994.- Love and Other Demons

- 2004.- Memory of my sad whores

- 2010.- I did not come to make a speech

See also:

- The colonel has no one to write to him, by Gabriel García Márquez

- Chronicle of a Death Foretold, by Gabriel García Márquez