Sharp order

When we look at a score and we are not used to it, it can sometimes be confusing to see so many symbols and numbers, especially knowing that each one has a specific function. Chances are that if you have started in music you have heard the term "sharps" and perhaps you know what they are for but it is difficult to find the way to write them. In this lesson from a TEACHER we will talk about sharp order, one of the basic rules fundamentals in writing and musical notation.

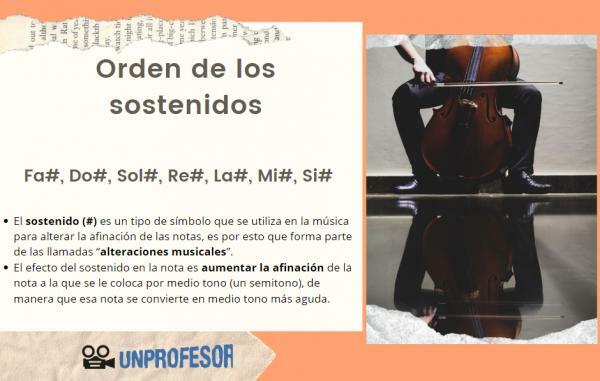

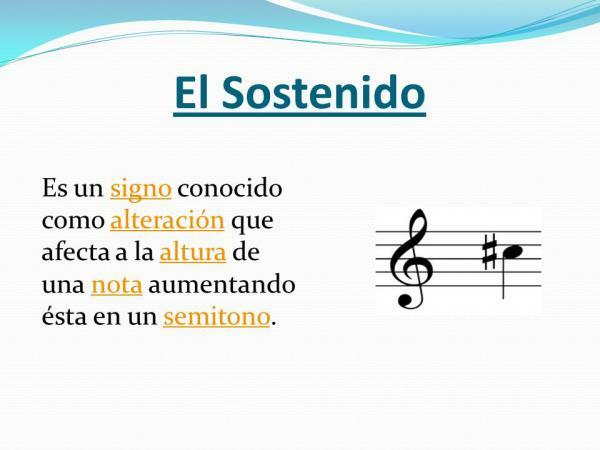

The sharp (#) is a type of symbol that is used in music to alter the pitch of the notes, that is why it is part of the so-called "musical alterations”. The effect of the sustain on the note is increase tuning of the note to which it is placed by half a tone (a semitone), so that note becomes half a tone higher.

Sharps can be used on individual notes, but they are often found in so-called “armor”At the beginning of a score and this is crucial for the performance of musical works.

Image: Slideplayer

Before knowing the order of the sharps it is important that we understand that

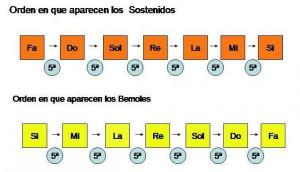

trusses are a set of alterations that, as we mentioned, are placed together at the beginning of a score or a section of the score to indicate the tonality of the work or that specific part of the work.The amount of alterations that is placed on an armor depends on the tonalityand they have a specific order and correct to be written. Important: this order is different for sharps and flats, since there is a specific order for writing sharps and another specific order for writing flats.

When a musical key signature is placed, this means that, for the rest of the work, those alterations must be followed using until the end changing those notes (unless otherwise indicated by means of another key signature different).

Image: Musical language with Cristina

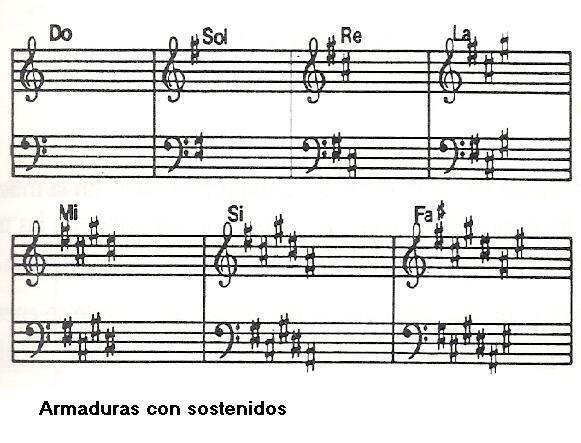

Since the different armors are placed depending on the tonality, you should know what tonality do you want to use to be able to find out which sharps and how many should be written on the key signature.

The amount of sustain in the keys comes from the musical scales. To make it easier, we are going to use the major scales as a reference so you can see it more clearly. These are the key signatures, the sharps and their amount on the major scales in order from least to most number of accidentals:

- C major: no alteration.

- G major: 1 alteration - fa #

- D major: 2 accidentals - F # and C #

- The biggest: 3 accidentals - F #, C # and G #

- My biggest: 4 accidentals - F #, C #, G # and D #

- B major: 5 accidentals - F #, C #, G #, D # and A #

- F # major: 6 alterations - F #, C #, G #, D #, A #, E #

- C # major: 7 alterations - F #, C #, G #, D #, A #, E #, Si #

Remember that there are not only major scales. In itself the key signature of a major scale is used exactly the same for its relative minor scale, thus that although it has the same number of alterations, it can be a major scale or a scale less. Even so, even in other scales such as Greek modes, the order for writing the accidentals is maintained.

Image: Musical language

Once all of the above is understood, we are already fully into knowing the order of the sharps. As you can see in the previous section, the amount of sustains is increasing in order of intervals of fifths. Do has no alteration, its fifth is G and it has 1 sharp. Re is the fifth of G and G has 1 alteration, so Re has 2 sharps... etc. In case you cannot memorize the order of the scales, you can think about this data.

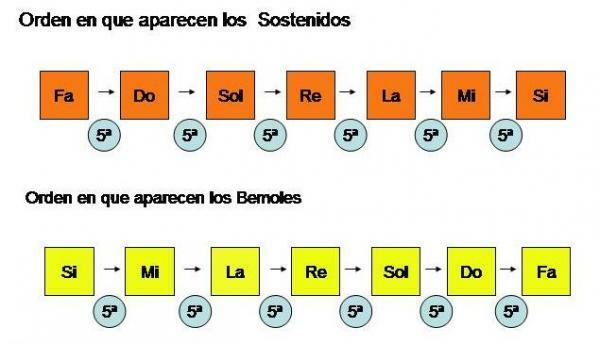

Now to write the sharps already knowing this you must memorize the order of the sharps, which is as follows:

Fa #, C #, G #, D #, A #, Mi #, Si #

If you have trouble memorizing the order, you can also resort to thinking about intervals again, as long as you know that the first sharp to be written is F #. The rest of the sharps, as in the keys, are added by fifths: C is the fifth of F, G is the fifth of C, D is the fifth of G... and so on.

Other musical alterations

- Flat: Shift the note half a tone downward (lower).

- Natural: Cancels the effect of sharps or flats.

There are also more accidentals but nowadays they are used as much lower frequencies, such as double sharp and double flat.

Although many elements of music theory may be strange and difficult to understand at first, remember that everything becomes easier with practice.

Image: Four Sixteenths