Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert: summary and analysis

Written by the French Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary It is the peak novel of literary realism of the nineteenth century. At the time, the novel aroused such scandal that Flaubert was prosecuted for it. The reason? The daring of his heroine, a character, whose treatment meant a real break with the literary tradition.

Bovarism They currently call the syndrome of people who, by idealizing love, become disillusioned shortly after starting a love relationship. But is it that Flaubert just recreated the story of a capricious woman?

The novel appears to have been inspired by the case of a woman named Veronique Delphine Delamare, she who had numerous lovers while she was married to a doctor, and she ended up committing suicide in 1848. The case quickly caught the attention of the press at the time.

Written and published by facsimiles in the magazine La Revue de Paris Throughout the year 1856, the novel will be published as a complete work in 1857. Since then,

Madame Bovary it marked a turning point in 19th century literature.Resume

A voracious reader of romance novels, Emma has many illusions about marriage and life, from which she expects passionate and gallant adventures. Excited, the young woman marries Charles Bovary, a doctor by profession. However, the reality will be different.

Become Madame Bovary, Emma meets a faithful husband, but absent, puritan, without character and without ambitions. Ignored and bored, she falls ill and her husband decides to take her to a town called Yonville, where she will give birth to her daughter Berthe.

The town pharmacist, Mr. Homier, fuels Emma's ambitions to profit economically and politically from her relationship with Dr. Bovary. Emma pressures her husband to take medical risks that bring him fame while he shops compulsively luxury goods to Mr.Lheureux, a salesman who plunges her into a sea of debt unpayable.

At the same time, Emma will have an affair with a Don Juan named Rodolphe Boulanger, but he leaves her standing on the day of her escape. Madame Bovary falls ill again. To cheer her up, her naive husband consents to her attending piano lessons in Rouen, unaware that his Her purpose was to become romantically involved with Léon Dupuis, a young man whom she had long known in Yonville. behind.

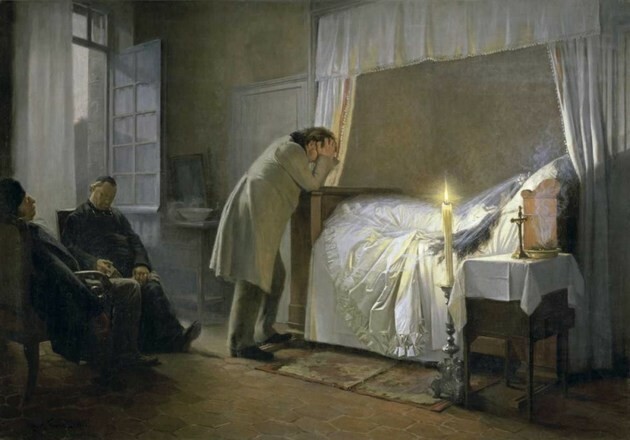

Her world falls apart when she receives a seizure and eviction order, and she finds no financial help from either Léon or Rodolphe, her former lover. Desperate, she decides to commit suicide with arsenic from Mr. Homier's pharmacy. Charles, ruined and disappointed, ends up dying. The girl Berthe is left in the care of an aunt and as she grows up she will work in a cotton thread factory.

Main characters

- Emma Bovary or Madam Bovary, protagonist.

- Charles Bovary, physician, husband of Emma Bovary.

- Mr. Homais, a pharmacist from the town of Yonville.

- Rodolphe Boulanger, wealthy, upper-class lady, Emma's lover.

- Leon Dupuis, Emma's young lover.

- Mr Lheureux, unscrupulous salesman.

- Berthe Bovay, daughter of Emma and Charles.

- Mrs. Bovary, mother of Charles and mother-in-law of Emma.

- Monsieur Rouault, Emma's father.

- Happiness, a domestic worker at the Bovary house.

- Justine, an employee of Mr. Homais.

Analysis

Many of the readers of this novel have been slow to reflect on Flaubert's possible sympathy or rejection of the female cause. While some affirm that he vindicates the woman, others think that he, on the contrary, places her on the dock by making lawlessness a fundamental feature of her character. These positions seem forced to our eyes. Gustave Flaubert goes much further by representing a universal and particular human drama at the same time.

Through the relationship between Emma and romantic literature, Flaubert highlights the symbolic power of aesthetic discourses. The literature that Emma reads voraciously can be seen here as a silent character, luck of the addresser that she acts as a catalytic force for the heroin's actions. In fact, Mario Vargas Llosa, in his essay The perpetual orgy, holds:

A parallel that all commentators, from Thibaudet to Lukacs, have insisted on is that of Emma Bovary and Don Quixote. The manchego was a misfit to life because of his imagination and certain readings, and, like the Norman girl, his tragedy consisted in wanting to insert his dreams into reality.

Both characters, fascinated by the obsession of voracious and disorderly reading that infuses their spirits, have set out on the path of their vain illusions. Almost two hundred and fifty years after Don Quixote, Madame Bovary will become the herointo "Misfit."

Flaubert will take charge of representing that universe before our eyes: on the one hand, the universe of reality regulated and regulated by the prevailing bourgeois order. On the other, the inner universe of Madame Bovary, no less real than the first. And it is that for Flaubert, Emma's inner world is a reality, because it is this that mobilizes the actions that build the story and push the characters to unsuspected outcomes.

Certainly, Gustave Flaubert breaks with the traditional way of representing the female personality: Madame Bovary will not be a devoted wife and mother. On the contrary, she will be a woman obedient to her passions without stopping to think about the consequences.

In this way, the author turns his back on the stereotype of the docile and harmless woman, complacent and fulfilling of her duty, as well as the woman made the hero's spoil. Flaubert reveals a complex person, a being with desire and will that can also be corrupted. It shows a woman who yearns for freedom and who feels that even the possibility of dreaming has been taken from her for being a woman. In this regard, Mario Vargas Llosa points out:

Emma's tragedy is not being free. Her slavery appears to her not only as a product of her social class - a small bourgeoisie mediated by certain means of life and prejudices - and of her condition as her provincial - a minimal world where the possibilities of doing something are scarce - but also, and perhaps above all, as a consequence of being woman. In fictitious reality, being a woman constrains, closes doors, condemns options that are more mediocre than those of men.

Emma is caught at the same time in the compulsion of the imaginary world, inspired by literature romantic, and in the compulsion of ambition, inspired by the new socio-economic order of the century XIX. Conflict is not just about domestic life being boring or routine. The problem is that Emma has nurtured an expectation that does not find space in reality. She craves the pathos that her literature has shown him, that other life. She has nurtured the desire and the will that a woman has been denied. She craves the life of a man.

Two factors are key: on the one hand, she is an adulterous woman, eroticized, with sexual desire. On the other, the seduction exercised in her by the mirage of prestige and power, the misplaced aspiration of an economic reality that is not her own, hunger of World. In fact, Mario Vargas Llosa maintains that Emma comes to experience the desire for love and money as a single force:

Love and money support and activate each other. Emma, when she loves, needs to surround herself with beautiful objects, beautify the physical world, create around a setting as sumptuous as her feelings. She is a woman for whom enjoyment is not complete if it does not materialize: she projects the pleasure of the body in things and, in turn, things increase and prolong the pleasure of the body.

Have only her books fueled that fascination? Could such concerns come only from them? For these questions to be answered with a yes, the other characters would have to have been the opposite of Emma: people of a rational and critical spirit, with their feet firmly on the land. It is not the case of Charles Bovary, her husband, although it is the case of her mother-in-law.

Charles Bovary is no closer to reality than Enma. On the contrary, he is absolutely incapable of seeing reality before his eyes, and he has not had to read any books to do so. Before Emma's dramatic turnaround, Charles was already living outside the real world, locked in the bubble of compliant and puritanical life, obeying the social order. The two live with their backs to reality, alienated. They both live in the fiction of their fantasies.

For Charles, Emma does not exist as a subject but as an object of devotion. She is part of the repertoire of accumulated goods to enjoy bourgeois status. He ignores the signs of distance from him, of her contempt and deception of him. Charles is an absent man, lost in his own world.

To say more, Charles is blatantly ignorant of the family's finances. He has ceded all administrative power to Emma, putting himself in the position that traditionally corresponded to women. At the same time, Charles treats Emma as a girl would treat the dolls she destined for the display case. He has the docility of the female stereotype, which Emma rejects. Two solitudes inhabit the Bovary house, far from being a home.

Flaubert reveals the social tensions present in the bourgeois life of the 19th century and that that generation seems not to recognize. Social ideology is also a fantasy, an imaginary construction that, unlike literature, appears inhuman, inflexible, artificial, but truly controlling.

Bourgeois ideology feeds, precisely, on vain illusion. He makes Emma believe that she can aspire to a life of luxury and prestige, as a princess without responsibilities. It is the new order that supposes the political and economic transformation of the XIX century and that seems to guide society to an unnoticed scenario. Vargas Llosa will say:

In Madame Bovary (Flaubert) he points out that alienation that a century later will take hold in the developed societies of men and women (but especially of the latter, for her living conditions): consumerism as an outlet for anguish, trying to populate with objects the void that life has installed in the existence of the individual modern. Emma's drama is the interval between illusion and reality, the distance between desire and its fulfillment.

That is the role, for example, of Mr. Homier and the salesman Lheureux: to feed Emma's ambition, then to bend her spirit and take advantage of it.

If she Emma seems at first to have achieved the autonomy of a man and to have managed to reverse her roles in her personal relationships, her delusional character, her constant Her comparison between her expectations and her reality (which she perceives as degraded) makes her an easy target for the social game, still dominated by the men she loves equalize.

One might wonder to what extent Emma manages to be the owner of her actions or rather she is at the mercy of the control of others. This apparently libertarian woman, who claims her space as a subject of self-determined pleasure and happiness, in a certain sense succumbs to the webs that the men around her weave for her.

The break occurs in the order of the imaginary. If Emma cannot dream, if reality is imposed with her punishing discipline, if she must abide by her role as her woman in society, life will be her own death for her.

In this way, Gustave Flaubert creates a literary universe in which the interrelation of the real world with the imaginary world is possible. Both universes are, according to the narrative, dependent on each other. This explains why for authors like Mario Vargas Llosa Madame Bovary It is not the first realistic work, but the one where romanticism is completed and opens the doors to a new look.

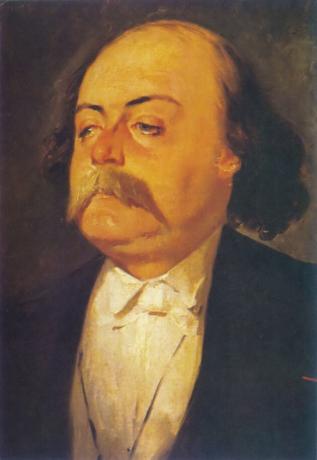

Short biography of Gustave Flaubert

Gustave Flaubert was born in Rouen, Normandy, on December 12, 1821. The writer Gustave Flaubert has been considered a distinguished representative of French realism.

Upon finishing high school, he studied law, but dropped out in 1844 as a result of various health problems, such as epilepsy and nervous imbalances.

He lived a serene life in his country house at Croisset, where he wrote his most important works. Even so, he was able to travel to various countries between the years 1849 and 1851, which allowed him to fan his imagination and hone his writing skills.

The first work he wrote was The temptations of Saint Anthony, but this project was shelved. After that, he started working on the novel Madame Bovary for a period of 56 months, which was first published in a serial. The novel caused a great scandal and he was prosecuted for immorality. However, Flaubert was found not guilty.

Among some of his works we can point out the following: Rêve d'enfer, Memoirs of a madman, Madame Bovary, Salambo, Sentimental education, Three stories, Bouvard and Pécuchet, The temptations of Saint Anthony, among other.

She passed away on May 8, 1880 at the age of 59.

If you liked this article, you may also be interested in: The 45 best romance novels