The Vitruvian Man by Leonardo da Vinci: analysis and meaning of the canon of human proportions

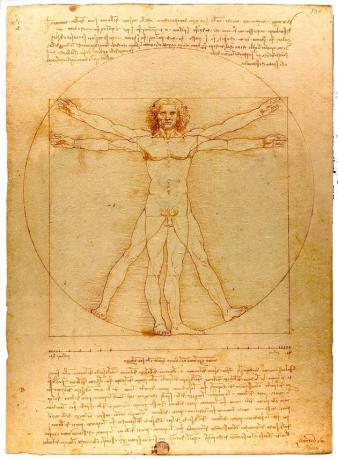

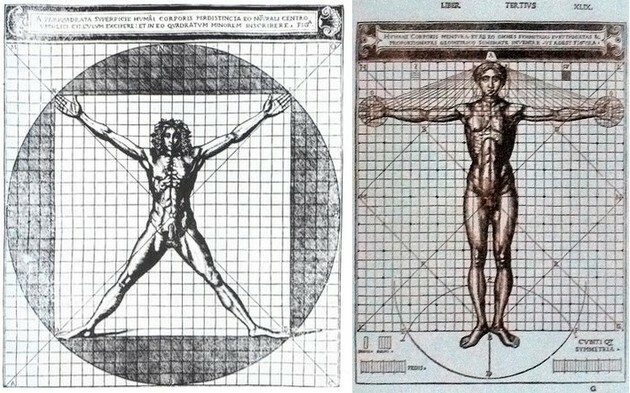

Is named Vitruvian man to a drawing made by the Renaissance painter Leonardo da Vinci, based on the work of the Roman architect Marco Vitruvius Polión. On a total surface of 34.4 cm x 25.5 cm, Leonardo represents a man with arms and legs extended in two positions, framed within a square and a circle.

The artist-scientist presents his study of the "canon of human proportions", the other name by which this work is known. If the word canon means "rule", then it is understood that Leonardo determined in this work the rules that describe the proportions of the human body, from which its harmony and beauty.

Besides graphically representing the proportions of the human body, Leonardo made annotations in specular writing (which can be read in the reflection of a mirror). In these annotations, he records the criteria necessary to represent the human figure. The question would be: what do these criteria consist of? In what tradition does Leonardo da Vinci subscribe? What did the painter contribute with this study?

Background of the Vitruvian man

The effort to determine the correct proportions for the representation of the human body has its origins in the so-called Ancient Age.

One of the first comes from Ancient Egypt, where a canon of 18 fists was defined to give the full extension of the body. On the other hand, the Greeks, and later the Romans, devised other systems, which tended to be more natural, as can be seen in their sculpture.

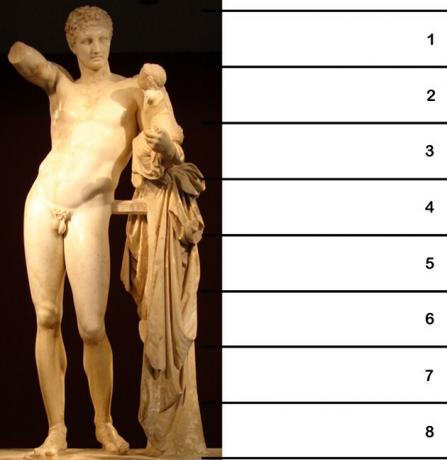

Three of these canons would transcend history: the canons of the Greek sculptors Polykleitos and Praxiteles, and that of the Roman architect Marco Vitruvius Polión, in whom Leonardo would be inspired to develop his proposal so celebrated in the present.

Canon of Polykleitos

Policleto was a sculptor of century V a. C., in the middle of the Greek classical period, who dedicated himself to elaborating a treatise on the proper proportion between the parts of the human body. Although his treatise has not come down to us directly, he was referred to in the work of the physicist Galen (1st century AD). C) and, furthermore, it is recognizable in his artistic legacy. According to Policleto, the canon should correspond to the following measures:

- the head must be one seventh of the total height of the human body;

- the foot should measure two hands;

- the leg, up to the knee, six hands;

- from the knee to the abdomen, another six hands.

Canon of Praxiteles

Praxiteles was another Greek sculptor from the late classical period (4th century BC. C.) who devoted himself to the mathematical study of the proportions of the human body. He defined the so-called "canon of Praxiteles", in which he introduced some differences with respect to that of Polykleitos.

For Praxíteles, the total height of the human figure must be structured in eight heads and not seven, as Polykleitos proposed, which results in a more stylized body. In this way, Praxíteles was oriented to the representation of an ideal canon of beauty in art, rather than to the exact representation of human proportions.

Canon of Marcus Vitruvius Pollio

Marco Vitruvio Polión lived in century I a. C. He was an architect, engineer and writer who worked in the service of Emperor Julius Caesar. During that time, Vitruvius wrote a treatise called About the architecture, divided into ten chapters. The third of these chapters dealt with the proportions of the human body.

Unlike Polykleitos or Praxiteles, Vitruvius' interest in defining the canon of human proportions was not figurative art. His interest was focused on offering a reference model to explore the criteria of architectural proportion, since he found a harmonious "whole" in the human structure. In this regard, he stated:

If nature has formed the human body so that its members keep an exact proportion with respect to the whole body, the ancients also fixed this relationship in the complete realization of his works, where each of its parts keeps an exact and punctual proportion with respect to the total form of its construction site.

Later the writer adds:

The architecture is composed of the Ordination -in Greek, taxis-, from the Disposition -in Greek, diathesin-, of Eurythmy, Symmetry, Ornament and Distribution -in Greek, oeconomics.

Vitruvius also held that by applying such principles, architecture achieved the same degree of harmony between its parts as the human body. In this way, the figure of the human being was exposed as a model of proportion and symmetry:

As there is a symmetry in the human body, of the elbow, of the foot, of the span, of the finger and other parts, this is how Eurythmy is defined in the works already completed.

With this justification, Vitruvius defines the proportional relationships of the human body. Of all the proportions that it provides, we can refer to the following:

The human body was shaped by nature in such a way that the face, from the chin to the highest part of the forehead, where the hair roots are, measures one-tenth of its total height. The palm of the hand, from the wrist to the end of the middle finger, measures exactly the same; the head, from the chin to the crown, measures one eighth of the whole body; one sixth measures from the sternum to the roots of the hair and from the middle of the chest to the crown, one fourth.

From the chin to the base of the nose, it measures one third and from the eyebrows to the roots of the hair, the forehead also measures another third. If we refer to the foot, it is equivalent to one sixth of the height of the body; the elbow, a quarter, and the chest is also equal to a quarter. The remaining members also keep a proportion of symmetry (…) The navel is the natural center point of the human body (...)”

Vitruvian translations in the Renaissance

After the disappearance of the Classic World, the treaty About the architecture Vitruvius had to wait for the awakening of Humanism in the Renaissance to rise from the ashes.

The original text had no illustrations (possibly they were lost) and was not only written in ancient Latin, but used highly technical language. This posed enormous difficulties in translating and studying the treatise. About the architecture of Vitruvius, but also a challenge for a generation as sure of itself as the Renaissance.

Soon appeared those who dedicated themselves to the task of translating and illustrating this text, which not only called the the attention of architects, but rather that of Renaissance artists, devoted to the observation of nature in his work.

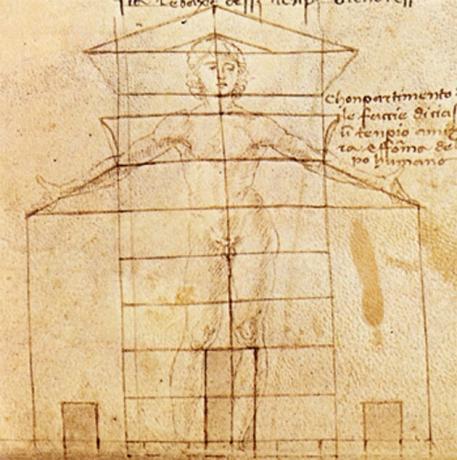

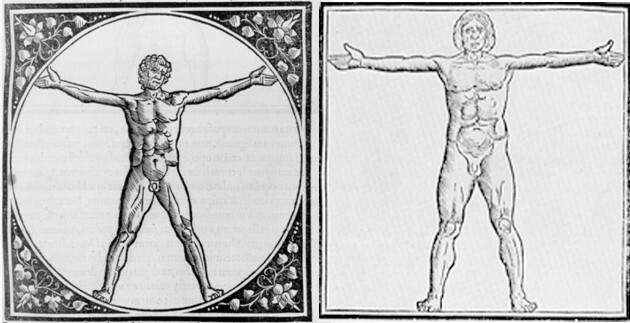

The valuable and titanic task began with the writer Petrarca (1304-1374), who is credited with having rescued the work from oblivion. Later, around 1470, the (partial) translation of Francesco di Giorgio Martini (1439-1502), an architect, appeared, Italian engineer, painter and sculptor, who produced the first Vitruvian illustration of which there is reference.

Giorgio Martini himself, inspired by these ideas, came to propose a correspondence between the proportions of the human body with those of the urban layout in a work called Trattato di architettura civile e militare.

Other teachers would also present their proposals with dissimilar results to the previous ones. For example, Friar Giovanni Giocondo (1433-1515), antiquarian, military engineer, architect, religious, and professor, published a printed edition of the treatise in 1511.

Besides this, we can also mention the works of Cesare Cesariano (1475-1543), who was an architect, painter and sculptor. Cesariano, also known as Cesarino, published an annotated translation in 1521 that would have a notable influence on the architecture of his time. His illustrations would also serve as a reference for Antwerp Mannerism. We can also cite Francesco Giorgi (1466-1540), whose version of the Vitruvian man dates from 1525.

However, despite the author's meritorious translations, none of them would be able to resolve central questions in terms of illustrations. It would only be Leonardo da Vinci who, at once curious and defiant with respect to the Master Vitruvius, would dare to go a step further in his analysis and transposition to paper.

The canon of human proportions according to Leonardo da Vinci

Leonardo da Vinci was a humanist par excellence. In it, the values of the multiple and learned man, typical of the Renaissance, meet. Leonardo was not only a painter. He was also a diligent scientist, doing research on botany, geometry, anatomy, engineering, and urban planning. Not satisfied with that, he was a musician, writer, poet, sculptor, inventor and architect. With that profile, the Vitruvian treatise was a challenge for him.

Leonardo made the illustration of the Man of Vitruvian man or Canon of human proportions around 1490. The author did not translate the work, but he was the best of his visual interpreters. By means of a thoughtful analysis, Leonardo made the pertinent corrections and applied exact mathematical measurements.

Description

In the Vitruvian man the human figure is framed in a circle and a square. This representation corresponds to a geometric description, according to an article presented by Ricardo Jorge Losardo and collaborators in the Journal of the Argentine Medical Association (Vol. 128, Issue 1 of 2015). In this article it is argued that these figures have an important symbolic content.

We must remember that in the Renaissance, at least among the elite, the idea of anthropocentrism circulated, that is, the idea that man was the center of the universe. In Leonardo's illustration, the circle that frames the human figure is drawn from the navel, and within it the entire figure that touches its edges with hands and feet is circumscribed. Thus, man becomes the center from which proportion is drawn. Even further, the circle can be seen, according to Losardo et al. As a symbol of the movement, as well as a connection with the spiritual world.

The square, on the other hand, would symbolize stability and contact with the terrestrial order. The square is thus drawn, considering the equidistant proportion of the feet to the head (vertical) with respect to the fully extended arms (horizontal).

See also Mona Lisa or La Gioconda painting by Leonardo da Vinci.

The annotations of Leonardo da Vinci

The proportional description of the human figure is outlined in the notes that accompany the Vitruvian man. To facilitate your understanding, we have separated Leonardo's text into bullets:

- 4 fingers make 1 palm,

- 4 palms make 1 foot,

- 6 palms make 1 cubit,

- 4 cubits make the height of the man.

- 4 elbows make 1 step,

- 24 palms make a man (...).

- The length of a man's outstretched arms is equal to his height.

- From the hairline to the tip of the chin it is one-tenth the height of a man; Y...

- from the tip of the chin to the top of the head is one eighth his height; Y…

- From the top of the chest to the end of the head he will be a sixth of a man.

- From the upper part of the chest to the hairline it will be the seventh part of the complete man.

- From the nipples to the top of the head it will be a quarter of the man.

- The greater width of the shoulders contains in itself a quarter of a man.

- From the elbow to the tip of the hand it will be a fifth of the man; Y…

- from the elbow to the angle of the armpit will be one eighth of the man.

- The whole hand will be one tenth of the man; the beginning of the genitals marks the middle of the man.

- The foot is the seventh part of a man.

- From the sole of the foot to below the knee it will be a quarter of the man.

- From below the knee to the beginning of the genitals will be a quarter of the man.

- The distance from the lower part of the chin to the nose and from the hairline to the eyebrows is, in each case, the same, and, like the ear, a third of the face ”.

See also Leonardo da Vinci: 11 fundamental works.

By way of conclusions

With the illustration of Vitruvian man, Leonardo managed, on the one hand, to represent the body in dynamic tension. On the other hand, he managed to solve the question of squaring the circle, whose statement was based on the following problem:

From a circle, build a square that has the same surface, only with the use of a compass and a ruler without graduating.

Probably, the excellence of this Leonardesque company would find its justification in the painter's interest in human anatomy and its application in painting, which he understood as a science. For Leonardo painting had a scientific character because it implied the observation of nature, geometric analysis and mathematical analysis.

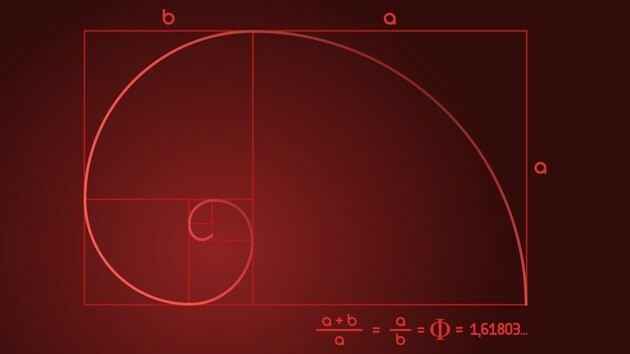

Therefore, it is not surprising the hypothesis of several researchers, according to which Leonardo would have developed in this illustration the golden number or the divine proportion.

The golden number is also known as the number phi (φ), golden number, golden section or divine proportion. It is an irrational number that expresses the proportion between two segments of a line. The golden number was discovered in Classical Antiquity, and can be seen not only in artistic productions, but also in the formations of nature.

Aware of this important finding, the algebraic Luca Pacioli, Renaissance, moreover, took care to systematize this theory and dedicated a treatise entitled The divine proportion in the year 1509. This book, published a few years after the creation of the Vitruvian man, was illustrated by Leonardo da Vinci, his personal friend.

The study of Leonardo's proportions has not only served artists to discover the patterns of classical beauty. In reality, what Leonardo did became an anatomical treatise that reveals not only the ideal shape of the body, but its natural proportions. Once again, Leonardo da Vinci surprises with his extraordinary genius.

It may interest you The 25 most representative paintings of the Renaissance