Differences between archaea and bacteria

The arches and the bacteria they are prokaryotes, unicellular living beings whose genetic material is not enclosed in an intracellular compartment.

Archaea were initially considered bacteria, and in fact they were known as archaebacteria. Thanks to the studies of Carl R. Woese and technological advances in genetic sequencing, archaea and bacteria were separated into different phylogenetic groups. Now living organisms are classified into three domains:

- Domain Bacterium: where are the bacteria.

- Domain Archaea: where arches are included.

- Domain Eukarya: where all eukaryotes (plants, fungi and animals) are included.

| Arches | Bacterium | |

|---|---|---|

| Domain | Archaea | Bacterium |

| Carbon bond of lipids | Ether | Ester |

| Lipid phosphate column | Glycerol-1-phosphate | Glycerol-3-phosphate |

| Metabolism | Similar to bacteria | Bacterial |

| Location | Extensive, they are located in extreme environments | Extensive |

| Transcription apparatus | Resembling eukaryotes | Bacterial |

| Nucleus and organelles | Absent | Absent |

| Methanogenesis | Present | Absent |

| Pathogens | Not | Yes |

| Ribosomal RNA subunit | 16S | 16S |

| Cellular wall | Does not contain peptidoglycan | Contains peptidoglycan |

| Spores | They do not form spores | Some bacteria form spores |

| Examples | Halobacterium salinarum | Escherichia coli |

Arches

Archaea are microscopic organisms that were discovered just 130 years ago, although they were initially thought to be bacteria. Archaea constitute the third branch of the tree of life, between bacteria and eukaryotes.

The first fully sequenced genome of an archaea was that of Methanococcus jannaschii published in 1996.

Characteristics of archaea

Archaea have a similar structure to bacteria: circular DNA, plasma membrane, cell wall, cytoplasm, and ribosomes. However, the cell membrane of archaea is characterized by the incorporation of isoprenoid lipids with ether bonds attached to a glycerol-1-phosphate base.

They have information processing systems like bacteria and eukaryotes, that is, DNA replication, transcription and translation, although they are more like the latter.

They are microscopic in size and can be as small as 400-500 nanometers. They have shapes similar to bacteria: rounded (cocci), cylindrical (bacilli) and irregular shapes. In fact, the first square microorganism (Haloquadratum walsbyi) was an archae discovered in 1980 on the Sinai Peninsula.

The archaea do not photosynthesize and do not form spores. They produce methane from biological compounds through the process of methanogenesis.

The archaea are beings that can live in extreme environments: or very high or very low temperatures. That is why they are classified as Extremophiles. However, not all Extremophilic organisms are archaea, nor are all Archaea extremophilic.

Until now, no pathogenic archaea, that is, that cause disease in animals or plants, are known.

Domain Archaea

The classification of archaea as a distinct domain arose from the studies of Carl Woese in the late 1960s using the ribosomal RNA sequence as a marker. Thus, these organisms form a separate self-domain from bacteria and eukaryotes, domain Archaea, which in turn presents several main divisions or rows that grow as new specimens are studied.

Crenarchaeota

Most are hyperthermophiles and thermoacidophiles. Thermoacidophils (including hyperthermophiles, which grow faster above 80ºC) colonize volcanic terrestrial environments and deep-sea hydrothermal vents. They can grow in the presence or absence of oxygen and be heterotrophic or autotrophic.

Examples of Crenarchaeota are Metallosphaera sedula (isolated from a volcano in Italy) and Thermoproteus neutrophilus (found in hot springs).

Euryarchaeota

A large number of families with varied habitats are grouped on this edge. For example, methanogens are found in anaerobic aquatic environments and in the gastrointestinal tract of animals, where participate in the conversion of organic matter by using the metabolic products of bacteria (for example CO2, hydrogen H2, acetate, and formate) and convert them to methane (CH4).

On the other hand, haloarchaeas live in hypersaline environments (such as salt flats, lakes, and the Dead Sea) where they grow as heterotrophs, often in association with phototropic algae. The square arch Haloquadratum walsbyi it is a halophilic representative.

Nanoarcheota

To this group belongs Nanoarcheum equitans, the smallest arch (400 nm) found so far. It was identified as small dots that grew next to another arch (Ignicoccus hospitalis).

Thaumarchaeota

This division was recognized in 2008 and its members are widely spread in medium-temperature marine environments. An example is the Nitrosopumilus maritimus, found in a tropical marine tank at the Seattle Aquarium in Washington (USA).

Bacteria

Bacteria are prokaryotic unicellular microorganisms, that is, they do not have a nucleus defined by a nuclear membrane. It is widely distributed in the biosphere and they were the first ancestral life forms.

There are more bacterial cells in the human body than there are human cells. The bacteria that reside in the intestine are called gastrointestinal microbiome and they play a fundamental role in the individual's state of health.

Of the great variety of known bacterial species, only a few are pathogenic for humans, the vast majority are harmless. Examples of pathogenic species are the Haemophilus influenza (which can cause meningitis and pneumonia in children under five years of age) and the Vibrio cholerae (causing cholera).

Bacteria characteristics

Bacterial cells possess circular chromosomal DNA, plasmids, cell membrane, cytoplasm, ribosomes, and cell wall.

The bacterial cell wall contains peptidoglycans composed of polysaccharide chains that are interconnected with unusual peptides. It works as a protective layer and shapes the bacteria. The forms of bacteria are varied; They can be spherical, cylindrical, spiral, or comma-shaped.

Some bacteria have a capsule outside the cell wall. The capsule allows bacteria to adhere to surfaces, protect against dehydration and attack by phagocytic cells.

The plasmids They are small pieces of DNA that are separated from the main DNA (chromosomal DNA) and that can be transmitted between bacteria.

Some species have flagella that are used for locomotion and pili that are used to adhere to surfaces.

Domain Bacterium

Bacteria are divided into two large groups according to their reaction to a staining technique: Gram-positive and Gram-negative. This stain was invented by Hans Christian Gram (1853-1938).

The Gram-positive bacteria they have a cell wall composed of up to 90% peptidoglycans and the rest of teichoic acids. Examples of Gram-positive bacteria are staphylococci Staphylococcus aureus found on the skin.

The gram-negative bacteria they have a relatively thin cell wall with only 10% peptidoglycans, covered by an outer envelope composed of lipopolysaccharides and lipoproteins. Examples of Gram-negative bacteria are meningococci Neisseria meningitidis, causative agent of meningococcal meningitis.

The Bacteria domain (formerly called Eubacteria) represents the first branch of the tree of life division. This group presents a great variety of rows of which we can mention:

- Proteobacteria: Gram-negative organisms such as Escherichia coli and the Salmonella sp.

- Chlamydias: Gram-negative aerobic pathogenic organisms such as Chlamydia trachomatis Y Chlamydia pneumoniae.

- Spirochetes: bacteria with wavy shapes such as Spirochaeta halophila.

- Cyanobacteria: bacteria that carry out photosynthesis.

- Gram-positive bacteria: such as lactobacilli, which produce lactic acid and are used in making yogurt.

You may be interested in the kingdoms of nature.

Differences between archaea and bacteria

The main differences between archaea and bacteria are in the composition of the cell membrane and wall, metabolism and genetic machinery.

Composition of the plasma membrane

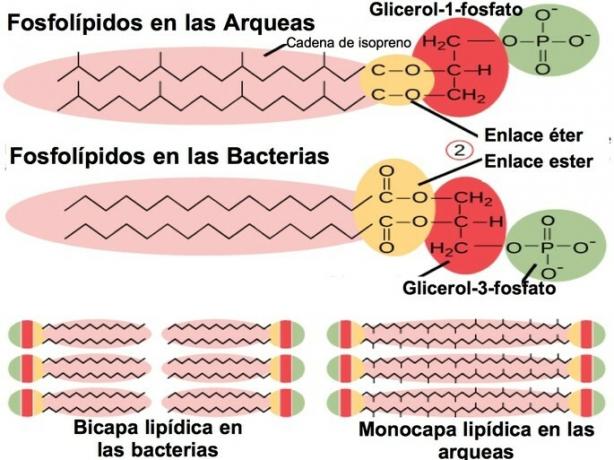

The cell membrane of archaea differs from bacteria in the type of phospholipids that make it up. Bacterial membrane phospholipids are made up of two linear chains of fatty acids, linked by ester bonds to a glycerol with a phosphate group on the third carbon. Two layers of these phospholipids make up the membrane. That is why it is called a lipid bilayer and is similar to the membrane structure of eukaryotes.

For their part, the phospholipids in the archaea membrane are made up of long chains (20 to 25 carbons) and branched of isoprenoids, which are attached at each end by ether bonds to a glycerol, which in this case has a phosphate group in the first carbon. This type of phospholipid forms a lipid monolayer.

Cellular wall

Unlike bacteria, the cell wall of archaea does not contain peptidoglycans and is made up of proteins, polysaccharides or glycoproteins. Some archaea have a pseudopeptidoglycan with different sugars in the polysaccharide.

Metabolism

One characteristic that distinguishes certain species of archaea from bacteria is their ability to generate methane from carbon dioxide and other organic compounds such as acetate and Format. Although archaea can generate their energy source from light, they do not carry out the process of photosynthesis, as cyanobacteria do.

Genetic machinery

The processing of genetic information in archaea is more like eukaryotes than bacteria. While there is a replication origin site in bacterial DNA, archaeological DNA has several replication initiation sites. The first amino acid in protein synthesis in bacteria is formyl-methionine, while in archaea it is methionine.

See also:

- Eukaryotic cell and prokaryotic cell.

- Virus and bacteria.