Postmodernity: characteristics and main authors and works

Postmodernity can refer both to the process of cultural transformation of modernity from the 1970s, and especially the 1980s, as well as to the different cultural, philosophical and artistic movements of that period that question the paradigms of modernity, as well as its universal validity and timeless.

If the particle post means 'after', does talking about postmodernity imply admitting that modernity and its values are over? Or does this just mean that modernity is simply in question? What does this expression really mean and what does it imply? How can you recognize a movement or thought postmodern?

The 70s, 80s and 90s were the decades of the triumph of capitalism and the welfare society, the fall of the Berlin Wall and the commodification of information and of all orders of life, that is, the triumph of the consumer society in the post-industrial societies.

For some authors, postmodernity is not exactly a critique of modernity, but rather a questioning of modernity. absolute character of certain values, such as the notion of "truth" and "reason", or the preeminence of the social over the individual. However, according to the defenders of postmodernity, it does not fail to recognize the importance of the values in question, but hardly calls into question the way in which they have been used. But are they right about it?

To understand postmodernity

Understanding postmodernity necessarily means having a clear point of reference: modernity. Modernity represents an era and a way of thinking whose antecedents can be traced back to the anthropocentrism of the Renaissance, although it did not take full shape until the 18th century.

An intellectual current and two historical events in the 18th century were fundamental in this turn of the history: the Enlightenment movement, also known as Enlightenment, the French Revolution and the Revolution industrial.

Roughly, modernity proposed the passage from tradition to change, which was called "progress." This involved:

- secularize society, that is, separate the Church from political power;

- promote knowledge (reason and science) as weapons against fanaticism and tools of progress;

- consolidate the national state (formation of nationalism), and create a new political model based on the separation of powers and the freedom of citizens;

- develop all the economic potentialities of industrialization.

But the history of the following centuries would show the seams of such an "inspiring" model: the expansion of imperialism, the emergence of communist ideology, the exacerbated nationalism that produced two world wars and other armed conflicts, the crack 29 and the cold war.

The appearance of new technologies (especially those of communication) would form a new scenario: the triumph of the consumer culture and mass culture. Is that the fulfillment of the promise? Is that what progress would be limited to? The disintegration of values, the loss of faith in the transcendence of the great historical stories and the uneasiness generated by boredom in the face of an absolutely commodified and mechanized culture would thus constitute the condition postmodern.

Characteristics of postmodernity

The features of modernity can be summarized in the following aspects:

- It expresses the crisis of modern metaphysical thought;

- It delegitimizes modern meta-stories;

- Recognize that there are different ways of knowing;

- It rejects historical linearity and relativizes progress;

- Reflect on its context and make visible responsibilities;

- It promotes subjective differentiation and diversity.

Let us therefore understand each of the characteristics of postmodernity carefully:

It expresses the crisis of modern metaphysical thought

The crisis of modern metaphysical thought begins, according to the authors, from the moment that philosophy and science discover that they are not infallible or universal, while discovering their inability to find a single "truth", which leads to the legitimacy of meta-stories modern. Postmodernity makes this break visible.

With modern metaphysical thought we refer to philosophy and science in the ways in which they are conceived in modernity. Modern science and philosophy have focused on upholding reason as a fundamental principle of human history, as well as on seeking and defending a single truth. But the ways in which world history has evolved call this claim into question.

Modern science and philosophy have been slow to reflect on the meaning of life and the purpose of knowledge based on absolute principles. That is, they have made the "Idea" prevail over reality and context, which is a cause of contradiction and discomfort.

It delegitimizes modern meta-stories

Science and philosophy, reason and truth, order and progress, State and nation, modernization and developmentare some of the fundamental meta-stories of modernity. All of them have emerged as universal and universalizing civilizing principles, just as religion would have been before.

If modernity wanted to bury religion in the holy field of private life, it also dug its own grave to one side by not keeping his promises, because among other things, when does progress come and what comes after it? If it is true that society benefits from progress from a historical perspective, is this sufficient consolation for individual existence?

The delegitimization of modern meta-stories is the consequence of several fissures, of which we list only three:

- pretending to give meaning to social life based on abstract principles (progress, reason, knowledge);

- submitting individuals to that social project denying subjectivities and diversities; Y

- remain with his back to the ways in which the appearance of technique and technology have dynamited those abstractions.

It is all this that creates, precisely, the social and cultural crisis of post-industrial societies that postmodernity reflects.

Recognize that there are different ways of knowing

For postmodernity, knowledge is not only scientific or philosophical, in that way, it relativizes the valuation of reason. For postmodernity, if something has shown the new way of life in which information is offered as merchandise, it is that there is also knowing-living, knowing-doing or knowing-hearing.

Along with this, for postmodernity the ways of "saying" and the appearance of knowledge in the form of information. For all this, the conception of knowledge according to modernity is transformed and the ideas of universal reason and absolute truth are relativized.

It is for all this that, not only for postmodern intellectuals but for the children of the postmodern era, symbols, language, icons, in short, the different ways of "saying" or "to mean".

Reject historical linearity and relativize progress

Modernity proposed the passage from tradition to change. This paradigm was called "progress", a horizon to which every society should aspire. That is the great meta-story of modernity.

For the modern mind, the progress It corresponded to a linear and evolutionary (ascending) view of time, the achievement of which would be possible based on three main elements:

- the domain of reason (knowledge),

- technological and industrial development and

- the consolidation of the modern national state (republics).

But despite the fact that many of the aspirations were achieved, it is also true that the contradictions did not take long to appear.

Postmodernity accepts that history is made up of breaks, returns, ramblings, unexpected jumps, in end, which is not oriented towards an ultimate end, but is complex and devoid of a meta-narrative that East.

Reflect on its context and make responsibilities visible

Some advocates of postmodern thinking argue that this line of thinking reflects on concrete facts, its consequences and the responsibilities of social actors, which implies for them the construction of a ethics.

Beyond affirming or denying this idea, it is clear that postmodern philosophy assumes its historical time. By this we mean that it tries to respond to its context and tries to understand the malaise of post-industrial societies.

They are post-industrial societies those that, after putting the industrial and capitalist model into practice, "enjoy" the wealth and stability generated by industrialization. That is, they are the societies that live what is known as the welfare state. Only that the fragmentation of the social order shows that something has not given the expected result.

Postmodernity shows that capitalism, together with technologies, has, on the one hand, fostered the individualization of subjects, and, on the other hand, it has modified the valuation of knowledge, the end of which is no longer the vindication of the spirit, but its commodification. If everything is marketable, if everything is reduced to consumption, then human transcendence is lost, since it has been deprived of its meaning.

Promotes subjective differentiation and diversity

If reason and absolute truth are relativized, postmodernity understands that there is a subjective differentiation and one diversity. The atomization of individuals, the triumph of the welfare society and its consequences, the fall of the great meta-stories and the loss of historical orientation, favor the differentiation of subjectivities.

In this scenario, the members of society no longer seek to become homogenized with the larger group, but to distinguish themselves, diversify, and in many cases, resist, passively or actively.

Meaning is not conferred by common discourse, such as belonging to the nation, but by individual pursuits, either alone or in a group. But these searches are not capable of articulating a new meta-story for post-industrial societies.

Therefore, the fact that postmodern thought makes this visible does not necessarily mean that it interprets it as a readjustment towards a new horizon. Postmodernists accuse this change as a sign of fragmentation of the social order, as an expression of a historical crisis.

For postmodernists, the delegitimization of the great meta-stories has not left in its place a new and hopeful discourse. Instead, he has left an individualized and hyper-commodified consumer society. He has finally left a fragmented society. This is, finally, the great failure of modernity.

Main authors and works of postmodernity

Jean-François Lyotard

It reflects on the condition of knowledge or knowledge in post-industrial societies. He was the author of the famous book The postmodern condition, as well as Postmodernity explained to children.

Jean Baudrillard

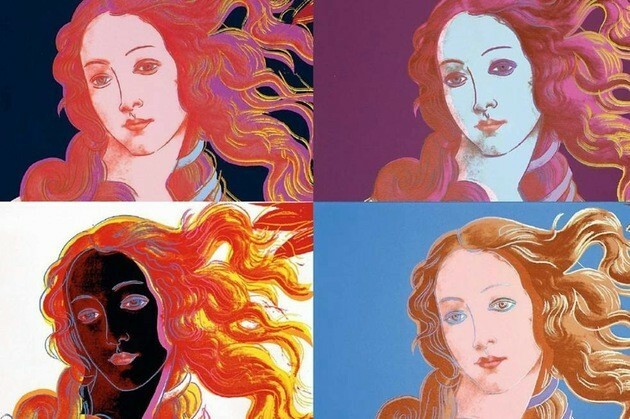

Among other debates, Baudrillard has reflected extensively on the commodification of symbols and, therefore, of social imaginaries. He is the author of the book The aesthetic illusion and disappointment.

Michel Foucault

Michel Foucault is widely known for his book This is not a pipe, in which he analyzes the paradox of the homonymous painting painted by the surrealist Renée Magritte.

Foucault studies the phenomena of language, meaning and signs. His accent is precisely on the modes of saying, the construction of signifying conventions, not only linked through the word. Among other of his fundamental works are: The words and the things Y Of language and literature.

Gilles Lipovestky

French author of the classic of postmodern philosophy The age of emptiness and of The times of hypermodernity, he reflects on social transformations: hyperconsumption, paradoxes of progress, human hopes and despair, from the notion of hypermodernity.

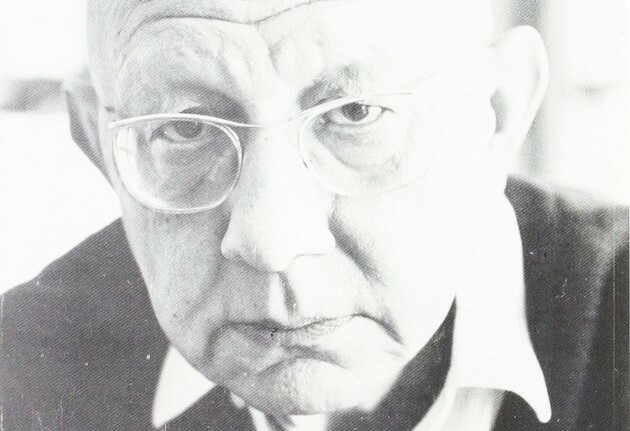

Gianni Vattimo

Vattimo is a philosopher born in 1936, trained from hermeneutics by Hans-Georg Gadamer. He developed the concept of weak thinking. He has analyzed the problem of the end of modern meta-stories and, after that, has devoted himself to the study of the role of religion and the evolution of religious thought in recent decades. The author of the books The end of modernity Y After christianity.

Cornelius castoriadis

He analyzes the problem of the construction of imaginaries and symbolism in the social environment. Castoriadis, from a neo-Marxist reading, highlights the problems derived from the structuring social order from the negotiations of meaning and the weight of institutions such as the Condition. He is the author of the book The imaginary institution of society.