Metric of the Mester de Clerecía

We are going to begin a new lesson from a TEACHER in which we will focus our efforts on analyzing the Metric of the Mester de Clerecía. During the centuries of the late Middle Ages, two great literary schools appeared in Europe and even competed with each other for some time. First the Mester of Juggler, throughout the eleventh century approximately, and after this came the Mester of clergy, during the twelfth century.

Both movements were in force until the end of the 15th century, when the Renaissance, and the two focus on the poetic genre, but each with its own special characteristics. In this case, we will focus on the metric in the Mester de Clerecía, and then we will know a little better this movement of which they are great representatives Gonzalo de Berceo and the Archpriest of Hita.

We begin by answering the theme that has brought us here, the meter of the Mester de Clerecía, and then we will know a little better what this medieval poetic movement consisted of.

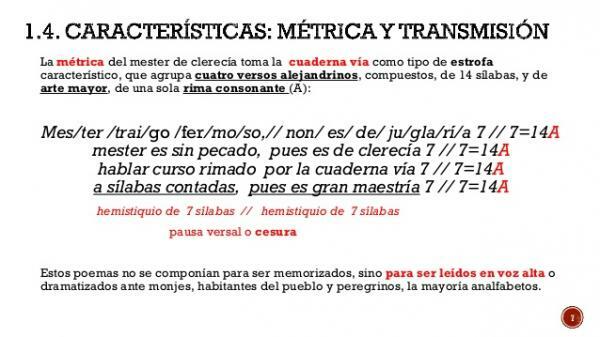

The basic metric used in this genre is known as

sash, which consists of a stanza composed of four verses. That is, it is a set of a quartet of verses, each one represents a line, and all of them are the result of a group of stanzas that form a complete poem.The verses that make up the stanzas of the cuaderna via have 14 syllables each and are popularly known as Alexandrians. In addition, they follow a scheme that we can call YYYY, and they all have the same rhyme, which in this case is consonant.

Let us remember that here we are interested in the consonant rhyme, which is different from the assonance, that is, it is the one in which the last rhyme is rhymed. consonants and vowels, while in the aforementioned assonance only the vowels do it.

To be perfectly clear, it is best if we look at an example. We are going to extract a stanza from the poem Miracles of Our Lady, by Gonzalo de Berceo, where we can count the 14 syllables of each Alexandrian verse.

Then this name of the Santa Regina

they heard the devils fled around the corner.

They all poured out like a mist,

leaving that petty soul abandoned.

We can observe the final rhymes: Regina - corner - haze - mean. They are all consonants, that is, with AAAA structure, and if you count their syllables, in each verse you will discover a total of 14.

We have already seen the metric of the Mester de Clerecía, where we observe some of the main features of this medieval poetic movement. However, other singularities can be extracted that make it unique and difference from Mester de Juglaría:

- A main characteristic is the literary language that is used, mainly cultured and full of lexical and syntactic resources, such as metaphors, allegories or symbolisms.

- The protagonists of the works are usually religious figures. It is not strange that the theme focuses on the miracles of the Virgin or some saint, or even God himself.

- The texts usually have an intentionality moralizing, sometimes through religion, others narrating national episodes that raise national sentiment.

- These works, unlike those of the Mester de Juglaría, which are oral, are always written.

- Now, instead of the minstrels, they are the clergymen those who write and even recite their own poems.

- Great respect is shown for the work on which each story or poem that is written is based, as when classical Greco-Roman themes are adapted, for example.

- Unlike in the Mester de Juglaría, where the author is not known, here it is of great importance.

In this other lesson we will talk to you concisely about the characteristics of the Mester de Clerecía.

We have already commented that the greatest exponents, that is, the most famous poets of the Mester de Clerecía, are both Juan Ruiz, the Archpriest of Hita, and Gonzalo de Berceo.

Without a doubt, the masterpiece, we believe that the only one, of the Archpriest of Hita, is the Good love book. This nobleman lived during the 14th century and left for posterity one of the great creations of Spanish literature, which combines religious themes with other more popular ones with moralizing intention, but always using cultured language and great rhythm narrative.

For its part, Miracles of Our Lady It is the great work of Gonzalo de Berceo, of which we have analyzed a stanza. This author was educated in Santo Domingo de Silos and San Millán de la Cogolla, true sanctuaries of the Castilian language, so the handling of his literary resources was outstanding.